Had Gadya The Only Kid: Lissitzky 1919

This page intentionally left blank

EDITED by Arnold J. Band INTRODUCTION by Nancy Perloff INTRODUCTION TRANSLATION ICONOGRAPHY VOCABULARY MUSIC FACSIMILE Published by the Getty Research Institute ReSources

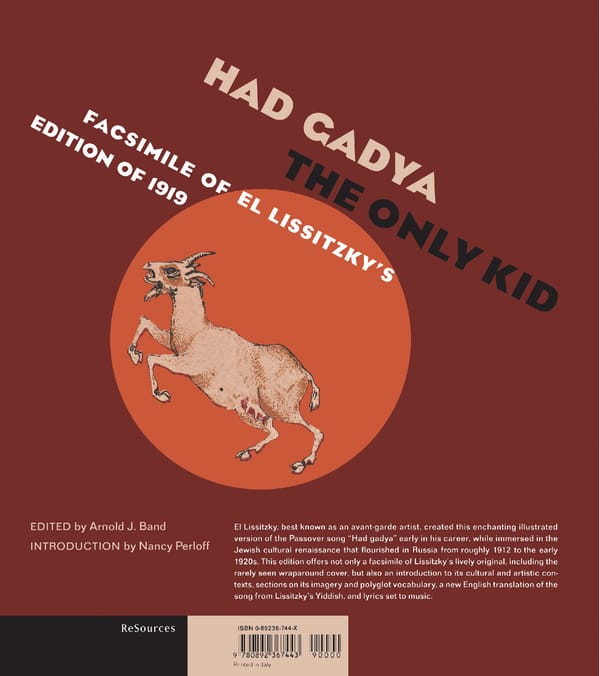

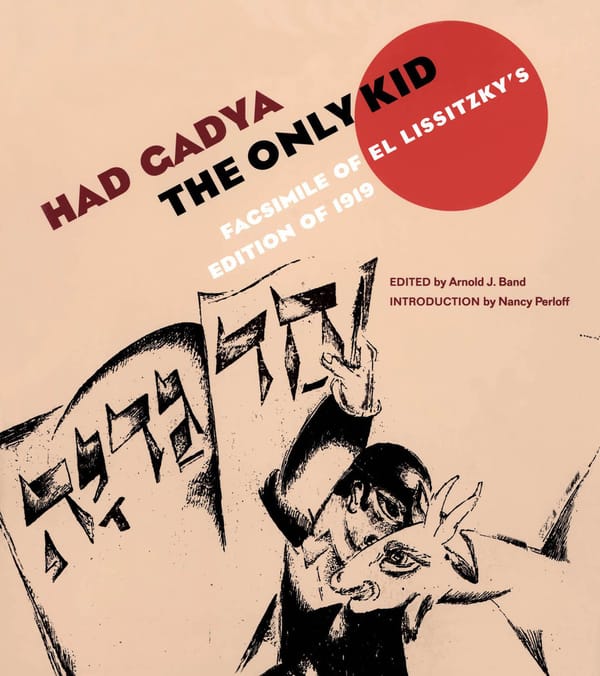

ARNOLD J. BAND is professor emeritus of Hebrew and comparative literature at the University of California, Los Angeles. His research focuses on the relationship between texts and historical contexts in Jewish literature of all periods and in modern Hebrew literature specifically. His publications include Nostalgia and Nightmare: A Study in the Fiction of S. Y. Agnon (1968); an annotated volume of translations of the Hasidic tales of Nahman of Braslav; and articles on subjects such as Franz Kafka, Hayyim Nahman Bialik, the Book of Jonah, semantic rhyme in Hebrew prosody, and modern Israeli fiction and poetry. Dr. Band founded the UCLA Department of Comparative Literature in 1969 and served as the director of the UCLA Center for Jewish Studies from 1994 to 1996. He has received a UCLA Dis tinguished Teaching Award, a National Endowment for the Humanities Fel lowship, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. NANCY PERLOFF is collections curator of modern and new media collections at the Getty Research Institute, where she focuses on acquisitions in European ReSources makes available primary materials and Russian modernism and in postwar music and the visual arts. Drawing held by Special Collections of the Research Library on the'holdings of the Getty Research Institute, Dr. Perloff has organized of the Getty Research Institute. These holdings, the exhibition Monuments of the Future: Designs by El Lissitzky (with Eva which range in date from the fourteenth century Forgacs, 1998) and the symposium "The Art of David Tudor: Indeterminacy to the present, include rare books, unpublished and Performance in Postwar Culture" (2001). She has published Art and the manuscripts, sketches, prints, photographs, archi Everyday: Popular Entertainment and the Circle of Erik Satie (1991) and tectural models, and the archives of artists, col essays on John Cage, Paul Gauguin, and the artistic partnership of El Lissitzky lectors, critics, and galleries. Offering scholarly and Kurt Schwitters. She is coeditor of Situating El Lissitzky: Vitebsk, Berlin, analyses that place these rich visual and textual Moscow (with Brian Reed, 2003). materials in context, the facsimiles, translations, monographs, edited collections, and exhibition catalogs in this series showcase exceptional sources that will further critical inquiry into all forms of art. —Thomas Crow, Director, Getty Research Institute THE GETTY RESEARCH INSTITUTE PUBLICATIONS PROGRAM PUBLISHED BY THE GETTY RESEARCH INSTITUTE, LOS ANGELES Thomas Crow, Director, Getty Research Institute Getty Publications Gail Feigenbaum, Associate Director, Programs 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Julia Bloomfield, Head, Publications Program Los Angeles, CA 900491682 Jeffrey Hurwit, Jacqueline Lichtenstein, Alex Potts, and www.getty.edu Mimi Hall Yiengpruksawan, Publications Committee © 2004 J. Paul Getty Trust HAD GADYA: THE ONLY KID 08 07 06 05 04 5 4 3 2 1 Edited'by Arnold J. Band Elizabeth May, Manuscript Editor LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGINGINPUBLICATION DATA Hillary Sunenshine, Designer Had gadya. Polyglot. Amita Molloy, Production Coordinator Had gadya = The only kid : facsimile of El Lissitzky's edition of 1919/ Printed and bound by Trifolio, Verona, Italy introduction by Nancy Perloff; edited by Arnold J. Band. p. cm. (ReSources) Text of Had gadya in Aramaic and Yiddish as part of illustrations, All works by El Lissitzky are © 2004 Artists Rights Society with English translation; introd. in English. (ARS), New York/VG BildKunst, Bonn, and are reproduced Includes bibliographical references, in this volume by permission. ISBN 089236744X 1. PassoverLiturgyTexts. 2. JudaismLiturgyTexts. 3. Had gadyaln art. I. Lissitzky, El, 18901941. II. Band, Arnold J. III. Getty Research Institute. IV. Title: Only kid. V. Title. VI. Series. BM670.H28L5712 2004 296.4'537dc22 2003017471

INTRODUCTION Nancy Perloff WITH HIS ILLUSTRATED BOOK OF THE PASSOVER SONG "HAD GADYA" Vitebsk was within the Pale of Settlement, the region, comprised of (The only kid), dated 6 February 1919, the Russian avantgarde artist El land annexed from Poland and Turkey, in which the majority of Russian Jews Lissitzky (18901941) had reached a pivotal moment in his career. For the past were forced to live from the late eighteenth century until 1917. A primary four years, he had focused almost exclusively on the study of Jewish folk concern of the czarist state in creating the Pale was to keep Jews from con culture and the design and illustration of books in Yiddish. Now, in summer ducting commerce in Russia proper. Periodically, however, permits to live 1919, he would join the faculty at the Popular Art Institute in Vitebsk (Vitebskoe outside the Pale were issued—to alleviate overcrowding or on account of an Narodnoe khudozhestvennoe uchilishche), where, inspired in part by the individual's profession or education—and as a result Jewish communities 2 suprematist painter Kazimir Malevich, he would turn to abstract painting. emerged in places such as Smolensk and Pochinok, just east of the Pale. Lissitzky's Had gadya marks the culmination of his artistic and personal Lissitzky's comingofage in and near the Pale would have been shaped engagement with Judaica. One of the last works that he signed under his by a powerful Jewish solidarity, the communitywide response to the knowl Hebrew given name, Eliezer, the book displays Lissitzky's interest, at once edge that Jews would never be considered true Russians. Throughout playful and reverent, in the languages and symbols of the Jewish culture. much of Lissitzky's parents' and grandparents' lives, the Jewish experience Instead of the traditional Aramaic, Lissitzky chose Yiddish for the song's in Russia was one of discrimination. During the 1820s, quotas were estab verses, which he set into architectural frames above the illustrations. Both lished to limit the presence of Jews in Russianlanguage schools and uni Aramaic and Yiddish are written in the Hebrew alphabet, but Yiddish, then versities, and large numbers of Jewish boys were conscripted into the army. the vernacular of Ashkenazic Jews, was apt to be more familiar to his audi Simultaneously, however, in an effort to assimilate Jews into the mainstream ence. Lissitzky did incorporate Aramaic, however, by introducing each new society, the state enacted policies of socalled Russification. For example, verse with an Aramaic phrase, printed on the lower righthand corner of the also in the 1820s, government schools were encouraged to retrain Jews in page. And for the pagination, he used decorative Hebrew letters, each of fields other than trade, that is, as farmers, craftsmen, or professionals. By the which has a numerical value. Though Lissitzky's focus in terms of subject early 1860s, after Czar Alexander N's relaxation of the conscription sys matter would soon change dramatically, in his experimentation with lan tem brought glimpses of freedom, Jews were given reason to hope that guage, typography, and architectural form, we can already see in the Had they could attain the status of true Russians. While the assassination of gadya many of the elements that would define his avantgarde work in the Alexander II in 1881 set off a wave of pogroms that continued until the revo following decades. lution of 1917, the popular uprisings of the revolution of 1905 forced Czar Lissitzky's decision to illustrate a traditional Passover song reflects both Nicolas II to institute reforms that transformed Russia from an autocracy into his religious upbringing and his participation as a young artist in the Jewish a constitutional monarchy. Subsequently, many of the restrictions on Jews cultural revival that took place in Russia from roughly 1912 to the early 1920s. were lifted, enabling them to create political parties and become eligible for Born in 1890 in Pochinok, a small market town just south of Smolensk, election to parliament. Though pogroms threatened the stability of this new Lissitzky grew up in the Russian (now Belarussian) city of Vitebsk. He was order, the relative political and artistic freedom that Jews enjoyed from 1905 raised by a pious Jewish mother and an intellectual father who prided him until the outbreak of World War I gave rise to a celebration of the Jewish heri self on being fluent in Russian, Yiddish, German, and English and on his gifts tage, specifically secular, among Russian Jewish artists—and it was within 3 as a translator. During his secondary school years, Lissitzky moved between this context that Lissitzky first developed an artistic identity. Smolensk, where he attended school and lived with his maternal grandpar At the center of this renaissance of Jewish secular culture was the ents, and Vitebsk, where he learned to paint traditional Jewish genre influential art critic Vladimir Stasov. Based in Saint Petersburg, Stasov had III scenes under the tutelage of Yehudah Pen, one of the few Russian Jewish close ties to leaders of the Jewish artistic and business communities who were artists to be accepted by the Imperial Academy of Arts (Imperatorskaia seeking to uncover and revive traditional Jewish art forms. With Baron David akademiia khudozhestv) in Saint Petersburg. After completing his studies, Gunzburg, the son of a wealthy businessman and philanthropist, Stasov helped Pen had returned to Vitebsk to open his own school of art in 1892, where, in publish a book of Jewish manuscript ornamentation, entitled L'ornement hebreu 1 4 addition to Lissitzky, he also taught Marc Chagall. (1905). Inspired by this work, the Jewish intelligentsia of Saint Petersburg

began collecting and publishing eastern European Jewish artifacts, both secular and religious. In 1912, with the financial help of Gunzburg's father, Baron Horace Gunzburg, and with the guidance of the folklorist and play wright Semyon Ansky, the Jewish Historical and Ethnographic Society (Evreiskoe istoricheskoetnograficheskoe obshchestvo) embarked on the Fig. 1. Eliezer (El) Lissitzky, title page in Moshe Broderzon, first of its journeys into the Pale of Settlement to collect Jewish religious and Sihes hulin: Eyne fun di geshikhten (Moscow: Nashe Iskusstvo, 1917). 5 Research Library, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles folk materials. Traveling through towns and villages of Ukraine, the expedi tion collected folk iconography in the form of tombstone engravings, Torah covers and breastplates, ark decorations, ornamental silver, spice boxes, and woodcuts. In 1916, Lissitzky took part in another expedition organized by the Jewish Historical and Ethnographic Society. With Issachar Ryback, a young art student who had undertaken an independent study of the wooden syna gogues in Belarus the previous year, Lissitzky was sent to explore the synagogues of Ukraine.6 The two artists drew plans, made colored draw ings, and collected inscriptions from about two hundred synagogues. In an article written in 1923, Lissitzky vividly recalled his study of the synagogue in Mohilev: "Searching for our identity, for the character of our times, we attempted to look into old mirrors and tried to root ourselves in socalled 'folkart.' Almost all the other nations of our time followed a similar path.... And therein you have the logical explanation of why I set out one summer to go among the people.'" Lissitzky praised the skillful work of the synagogue painter, the ability to make a "whole great world" come to life with just a few colors: "This is the very opposite of the primitive; it is the product of 7 great culture." Several sketches from Lissitzky's tour of the Mohilev syna gogue survive, including a black chalk and watercolor of a lion's head with a human face (Jerusalem, Israel Museum, Boris and Lisa Aronson Collection), an image that Lissitzky copied from the zodiac painting on the ceiling of the synagogue. Had Lissitzky and Ryback tried to publish inscriptions from the syna gogues they visited, they would have violated the Russian edict (ukaz) of July 1915 that banned publications using either Hebrew or Yiddish words. Indeed, despite the relative easing of restrictions on Jewish life in the Pale, this edict forced Jewish presses to shut down since it was now unlawful to Fig. 2. Eliezer (El) Lissitzky, front cover of Mani Leib, 8 mail anything that was printed in either Hebrew or Yiddish. However, after Yingl tsingl khvat (Warsaw: Kultur Lige, 1922). the revolution of February 1917 and the overthrow of the czar, the new Research Library, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles Provisional Government abolished laws that had barred Jews from citizen ship, and it repealed the decree prohibiting the printing of Hebrew letters, thereby sparking a sudden flurry of activity among the Jewish presses. In 1917, Lissitzky moved to Kiev, a center of the Jewish revival, and immersed that he intended to couple the style of the story with the "wonderful" style himself in the production of Yiddish book designs and illustrations. His first 9 of the square Hebrew letters. In the magnificently colored title page (fig. 1), IV commission was to design and illustrate Moshe Broderzon's Sihes hulin: a peacock pulls a Hasid up to heaven, while the scribes on the left and at Eyne fun di geshikhten (1917; An everyday conversation: A story), which bottom look up at the peacock, saluting the bird's traditional role as a source appeared in a small edition of 110 numbered copies; the majority were of spiritual inspiration. In 1918, with his original drawings for Mani Leib's Yingl printed as small booklets, but a few were printed in the form of a scroll and tsingl khvat C\ 922; The mischievous boy; fig. 2), Lissitzky incorporated Hebrew were encased in decorative wooden boxes. Lissitzky explained in the letters and typography into his overall design, a technique that anticipates colophon (set in an ornamental frame based on the shape of a Torah ark) 10 his work in the Had gadya book.

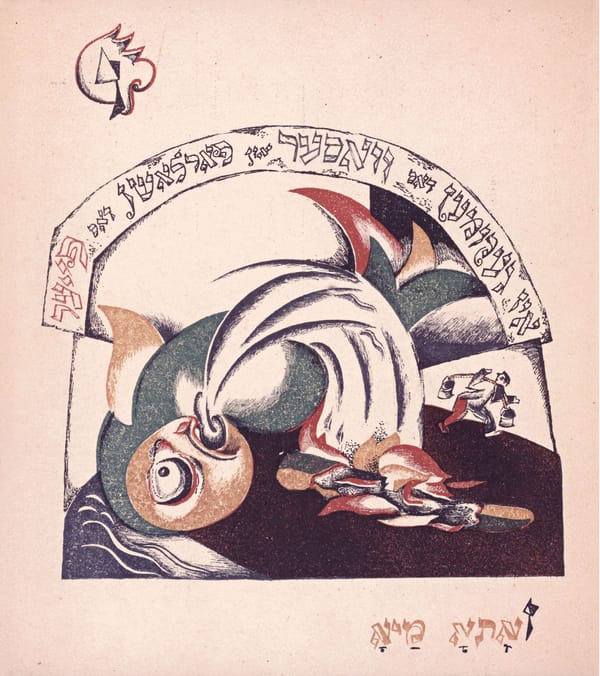

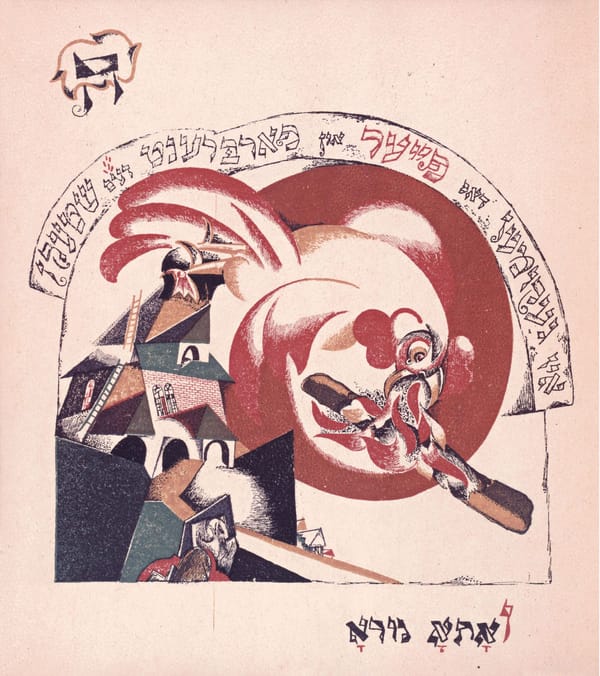

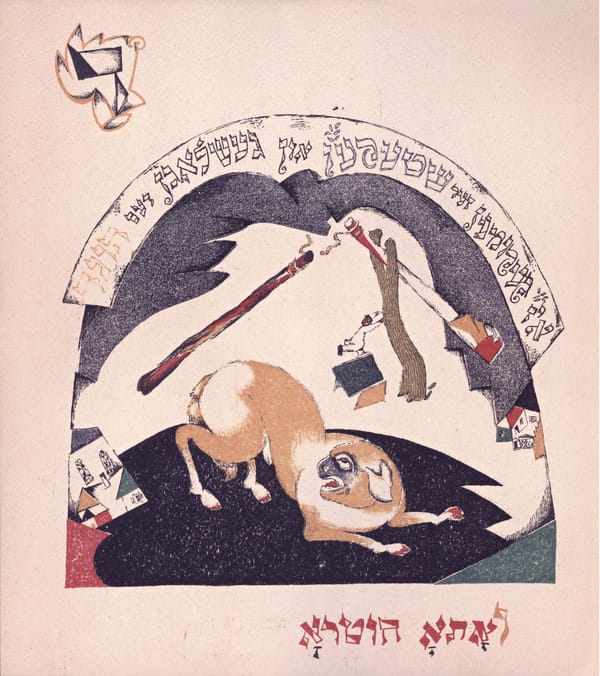

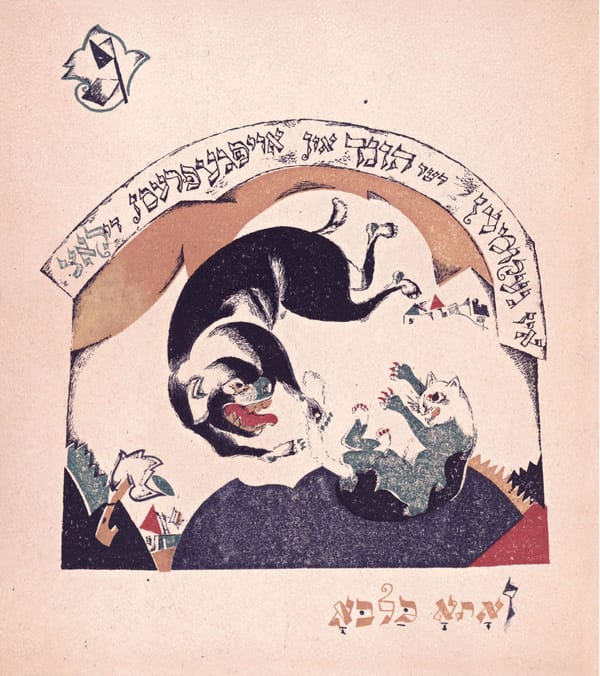

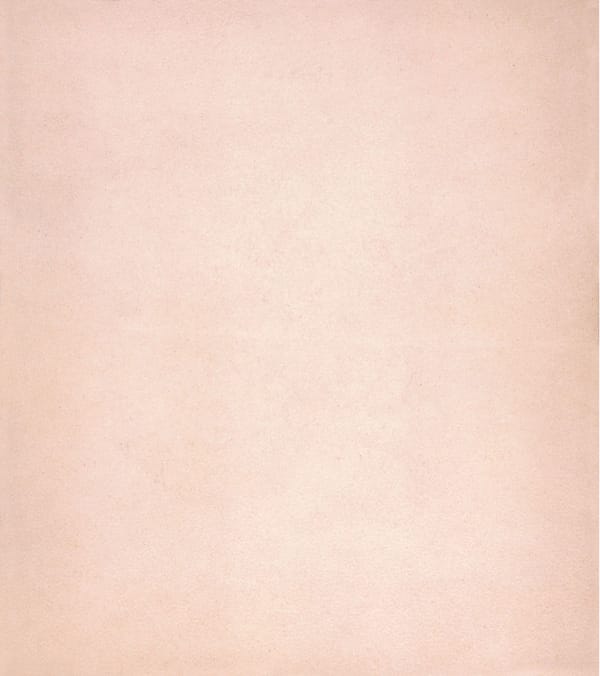

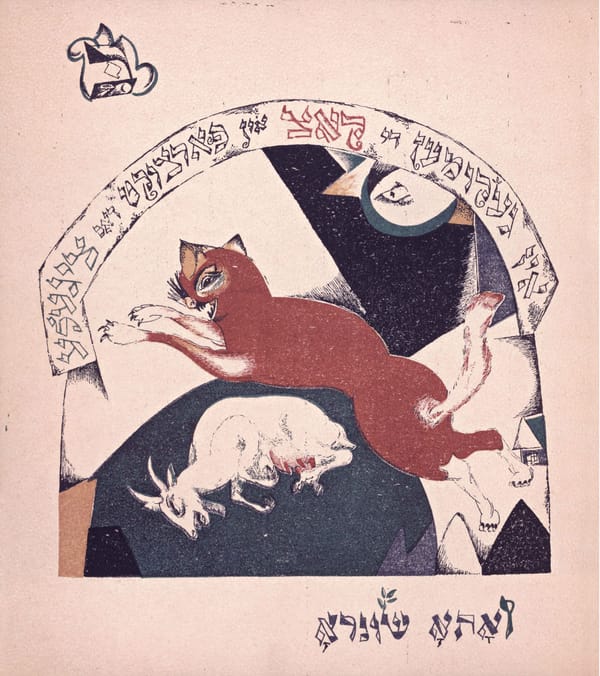

it as part of a complete illuminated Haggadah—of which many have been produced over the centuries—indicates that he viewed the song both as a message of Jewish liberation based on the Exodus story and as an allegorical expression of freedom for the Russian people. Several stylistic and icono graphic elements that were incorporated into the final two plates for the litho graphs of 1919 underscore Lissitzky's interest in the song as a parable of the Russian Revolution, of the defeat of the czarist rule and the victory and lib eration of the Russian masses. The angel of death, for example, who is shown slaying the slaughterer Fig. 3. Eliezer (El) Lissitzky, sketch for the final in verse 9 and then again as the victim of God's divine hand in the next verse of "Had gadya," 1917, watercolor, 29.8 x 26 cm and final verse, wears a crown, absent in the 1917 sketches, whose shape 3 1 (11 /4 x 10 /4in).TretyakovGallery, Moscow resembles that of czarist crowns as depicted in Russian folk art. In verse 10, the hand of God is strikingly similar to an image of a hand that appeared on one of the first series of stamps printed after the revolution of 1917. On the LISSITZKY'S EARLIEST ILLUSTRATIONS BASED ON THE "HAD GADYA" stamp, the hand is clearly a symbol of the Soviet people. And the angel of song were a set of brightly colored, folklike watercolors that he painted in death, who is depicted as dying in the set of illustrations from 1917 (see fig. 1917 (fig. 3). Two years later, he returned to the Passover song, first creating 3), is now dead—clearly, in light of the symbolic link to the czar, killed by the a series of watercolors and then, closely based on the watercolors, a set of force of the revolution.13 lithographs. The secular Yiddish organization Kultur Lige, of which Lissitzky The optimism expressed in Lissitzky's plate for the final verse is telling and fellow artists Natan Altman and David Shterenberg were founders, pub given the political situation in Russia in February 1919. The period in which lished the lithographs in book form in 1919 in an edition of seventyfive Lissitzky produced his lithographs was one of great violence. Although 11 copies. From the earliest drawings to the final plates, subtle but significant the Provisional Government of 1917 had announced the transformation of changes occurred in Lissitzky's treatment of the subject matter. By compar Russia into a liberal democratic and pluralistic state and had abolished ing the two versions, we can see that for Lissitzky the appeal of illustrating laws restricting citizens on the basis of religion or nationality, in October the song was twofold: not only did it enable him to create a modern piece of 1917 the Bolsheviks toppled the Provisional Government, and the country Judaica but it also allowed him to represent and comment on the Jewish descended into civil war. Yet even the potential victory of the Red Army was experience in Russia during these volatile years. obviously a great source of hope for young Russian Jewish artists like A folk song probably derived from a late medieval German source, Lissitzky, and in the imagery of his Had gadya, and especially the prostrate "Had gadya" was first included in the Passover service, the Seder, in the angel of death, Lissitzky posited this hope. 12 fifteenth century. Though not part of the service proper, the song appears In terms of the development of Lissitzky's artistic technique, the litho at the end of the Haggadah, the text used at the Seder. The song has a con graphs reveal several fascinating and novel approaches to typography and catenated, or linked, structure, and it introduces a series of characters, each design. Here we see an early example of Lissitzky's integration of letters and one destroying the last: a cat devours the kid, a dog gobbles up the cat, a images: for each verse, he arranges the words of the story to form an archi stick beats the dog, fire burns the stick, and so on, until God slays the angel tectural frame around the illustration. To connect text and image even fur of death, thus ending the chain of violence. The connection from verse to ther, and perhaps to make the book more accessible to young audiences, verse is not necessarily causal or logical; for instance, there is no particular Lissitzky invented a system of color coding in which the color of the princi reason why a cat would appear and eat the kid. The capricious nature of the pal character in each illustration matches the color of the corresponding song suggests that it may have been designed to capture and hold the atten word for that character in the Yiddish text. For instance, the kid in verse 1 is tion of young children until the conclusion of the Seder—certainly, it gave yellow, and the Yiddish word y^VPE (kid) in the arch above is also yellow; the Lissitzky the freedom to be whimsical in his illustrations. green hue of the father's face is matched by the green type used for the 14 The precise meaning of the "Had gadya" song is ambiguous, but, given Yiddish word PONO (father). While the bold colors and twodimensionality the context of the Passover Seder, which celebrates the story of the Exodus, of the lithographs are reminiscent of Chagall's work, the formal properties V it is traditionally thought to be a parable for the divine deliverance of the of the illustrations are also Cubistic in their use of geometric forms and Jewish people, whom Moses led out of Egypt and freed from bondage. The Futuristic in their use of the spiral to evoke motion. With their colorful flat different characters worsted in the song have been interpreted, by extension, ness, expressive distortions of proportion, rhythmic simplification of form, as nations that have attempted to destroy or oppress the Jewish people. and humorous and sometimes grotesque faces of beasts and humans, the Lissitzky's decision to let his Had gadya stand on its own, rather than publish Had gadya illustrations yield a sense of childlike fantasy.

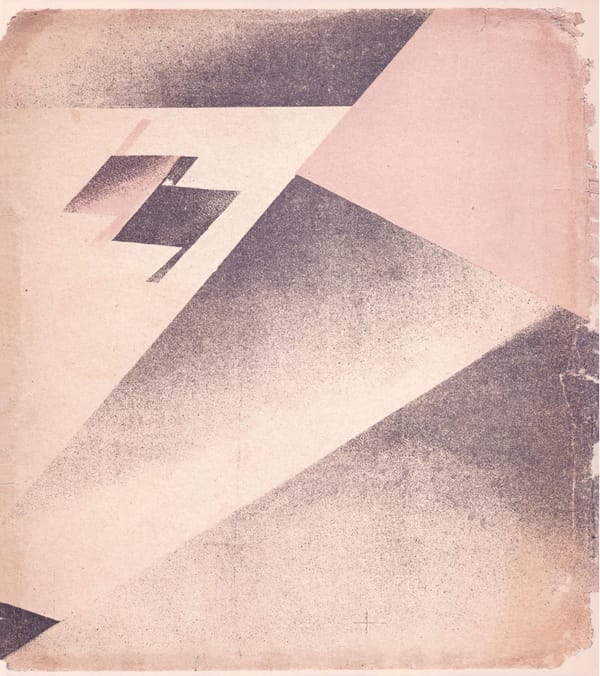

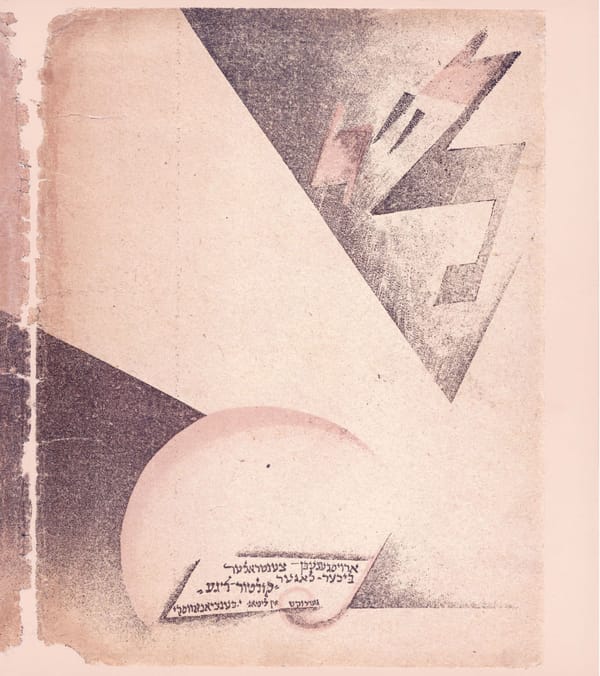

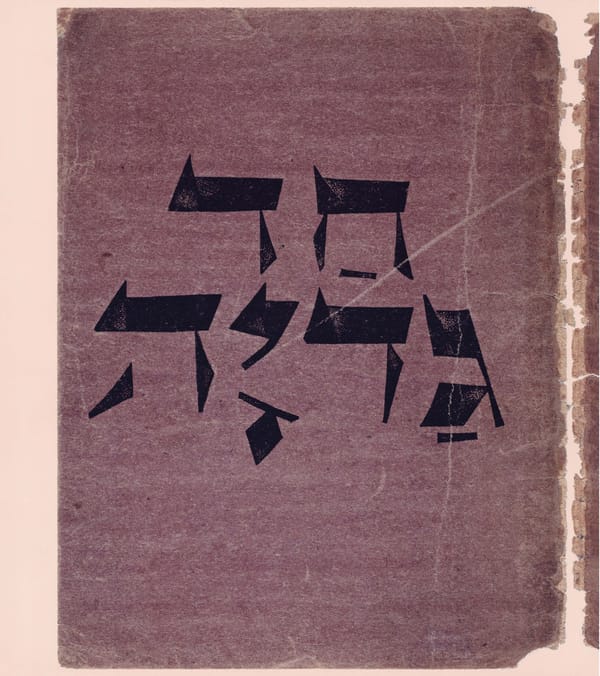

In his threepaneled dust jacket—designed to wrap around the entire The dust jacket reproduced here is held by the Research Library of the book—Lissitzky made a pronounced move away from the figurative, Chagall Getty Research Institute. It is one of only three known complete examples like traits of his colorful lithographs toward an abstract, CuboFuturist lan and it belongs to the small edition of seventyfive copies of the Had gadya guage consisting of fractured planes and triangles in ocher, black, and violet. 16 book that Lissitzky made in 1919. That so few of the dust jackets have sur The dust jacket bears no date but must have been completed sometime vived may be explained by the fact that they were less sturdy than the book after 6 February 1919, the date on the title page, and before he arrived in and so may have fared less well, particularly in children's hands. Also, whole Vitebsk in May The complete verses of the Passover song appear on the copies of the 1919 edition may have been destroyed during the Stalin era. lefthand interior panel of the dust jacket, while on the righthand panel a cir Though primarily in Yiddish, which in Russia had a longer life in print than cle overlaps a large polygon. In the center panel, set within another polygon, Hebrew since it was considered a proletariat language, the book would none are two smaller geometric shapes, each of which represents the Hebrew let theless have been associated with the traditional Jewish Passover service ter yud ('). Yudyud is one of several ways of expressing the name of God in and so may have been more vulnerable to government censorship. Hebrew letters. These letters are balanced by two other angular letters on Following the completion of his Had gadya, Lissitzky moved from Kiev the righthand panel, lamed (W and yud ('), most likely the first and last letters back to Vitebsk, where he taught painting alongside Malevich and where of Lissitzky's surname. The mixture of decorative Hebrew letters and flat cir he developed his own abstract geometric language, which he named Proun cular and triangular planes of color demonstrates the primacy of Lissitzky's (Proekt utverzhdenia novogo; Project for the affirmation of the new). He would concern with design, which he would later espouse as the basis of an inter make brief reference to his Jewish background by publishing the article on national language. The design of the dust jacket also suggests that Lissitzky the Mohilev synagogue in 1923 and also in several Proun works that incor already may have been familiar with the suprematist work of Malevich and porated Hebrew letters. But, chiefly, after the Had gadya project he pre Alexandra Exter: Malevich's paintings had been shown at the Tenth State Exhi sented himself as "El" Lissitzky, and he would soon travel to Berlin to further bition: NonObjective Creativity and Suprematism (Gosudarstvennaia vystavka: the exchange between the European and Russian avantgardes. Bespredmetnoe tvorchesto i suprematizm), which opened in Moscow in 15 January 1919, and Exter had her own studio in Kiev. NOTES 1. Seth L. Wolitz, "The Jewish National Art Renaissance in 6. Roskies, Against the Apocalypse (note 5). 12. Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion, s.v. "Had gadya." Russia," in Ruth ApterGabriel, ed., Tradition and Revolution: The Jewish Renaissance in Russian AvantGarde Art, 7. El Lissitzky, "The Mohilev Synagogue Reminiscences 13. Alan Birnholz, "El Lissitzky and the Jewish Tradition," 19121928, 2d ed., exh. cat. (Jerusalem: Israel Museum, (1923)," trans. Louis Lozowick, in Peter Nisbet et al., Studio International, no. 186 (1973): 131. For a discussion of 1988), 23. El Lissitzky 18901941, exh. cat. (Cambridge: Harvard the iconography, specifically the czarist crown and the University Art Museums, 1987), 5559. hand on the printed stamp, see Haia Friedberg, "Lissitzky's 2. Michael Hickey, "Revolution on the Jewish Street: Smolensk, Had Gadia'," Jewish Art 1213(198687): 292303. 1917," Journal of Social History 31 (1998): 82350; Avram 8. Wolitz, "Jewish National Art" (note 1), 41 n. 40; and Kampf, Chagall to Kitaj: Jewish Experience in 20th Century Art, Roskies, Against the Apocalypse (note 5), 138. 14. Haia Friedberg introduced the idea of this color coding in exh. cat. (London: Lund Humphries/Barbican Art Gallery, her article "Lissitzky's Had Gadia" (note 13), 29495. 1990), 15; and Wolitz, "Jewish National Art" (note 1), 41 n. 9. 9. Ruth ApterGabriel, "El Lissitzky's Jewish Works," in idem, ed., Tradition and Revolution: The Jewish Renaissance 15. ApterGabriel, "El Lissitzky's Jewish Works" (note 9), 116. 3. For a discussion of the history of the Jews in Russia in Russian AvantGarde Art, 19121928, 26 ed., exh. cat. during this period, see Michael Stanislawski, "The Jews (Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 1988), 104. 16. John Bowlt, as quoted in "The 'Vasari' Diary: A Child's and Russian Culture and Politics," in Susan Tumarkin Topography of Typography," Artnews 81, no. 7 (1982): 1317, Goodman, ed., Russian Jewish Artists in a Century of Change: 10. Editions of Yingl tsingl khvat were published in 1919 and announced the first known copy of the dust jacket, which 18901990, exh. cat. (Munich: Prestel/Jewish Museum, 1922; see Peter Nisbet et al., El Lissitzky, 18901941, exh. cat. was acquired by a Paris collector from a private seller in the New York, 1995), 1620. (Cambridge: Harvard University Art Museums, 1987), 180 former Soviet Union (p. 17). A second copy with a set of (cat. no. 1919/7), 183 (cat. no. 1922/1). lithographs was sold at Christie's, London, 26 June 1986; see 4. Wolitz, "Jewish National Art" (note 1), 25; and Kampf, Nisbet et al., El Lissitzky (note 10), 179 (cat. no. 1919/1). VI Chagall to Kitaj (note 2), 1516. 11. Centered in Kiev, Kultur Lige played a prominent role in The dust jacket and lithographs reproduced here were obtained the renaissance of Jewish secular traditions in Russia in the by the Research Library of the Getty Research Institute in 5. Scholars disagree about the date of the first expedition early part of the twentieth century. Its mission was to create a February 1997 from a private dealer in New York. of the Jewish Historical and Ethnographic Society; see modern Jewish art that incorporated Jewish folk traditions. Kampf, Chagall to Kitaj (note 2), 16; Wolitz, "Jewish National Kultur Lige published historic studies, teaching materials, liter Art" (note 1), 25; and David Roskies, Against the Apocalypse: ary journals, graphic work, and children's books; see Hillel Responses to Catastrophe in Modern Jewish Culture Kazovsky, The Artists of the KulturLige (Jerusalem: Center for (Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1984), 281. Jewish Art, 2003).

HAD CADYA THE ONLY KID TRANSLATION by Arnold J. Band The only kid, the only kid Then came the shohet and slaughtered the ox That the father bought for two zuzim, That drank the water The only kid, the only kid. That quenched the fire That burnt the stick Then came the cat and devoured the kid That beat the dog That the father bought for two zuzim, That gobbled up the cat The only kid, the only kid. That devoured the kid That the father bought for two zuzim, Then came the dog and gobbled up the cat The only kid, the only kid. That devoured the kid That the father bought for two zuzim, Then came the angel of death and butchered the shohet The only kid, the only kid. That slaughtered the ox That drank the water Then came the stick and beat the dog That quenched the fire That gobbled up the cat That burnt the stick That devoured the kid That beat the dog That the father bought for two zuzim, That gobbled up the cat The only kid, the only kid. That devoured the kid That the father bought for two zuzim, Then came the fire and burnt the stick The only kid, the only kid. That beat the dog That gobbled up the cat And the Holy One came, Blessed be He, and slew the angel That devoured the kid of death That the father bought for two zuzim, That butchered the shohet The only kid, the only kid. That slaughtered the ox That drank the water Then came the water and quenched the fire That quenched the fire That burnt the stick That burnt the stick That beat the dog That beat the dog That gobbled up the cat That gobbled up the cat That devoured the kid That devoured the kid That the father bought for two zuzim, That the father bought for two zuzim, The only kid, the only kid. The only kid, the only kid. Then came the ox and drank the water That quenched the fire That burnt the stick That beat the dog VII That gobbled up the cat That devoured the kid That the father bought for two zuzim, The only kid, the only kid.

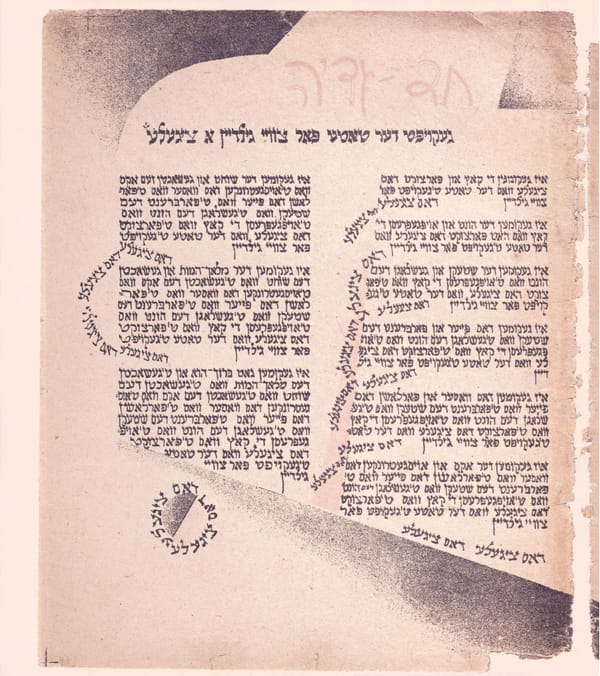

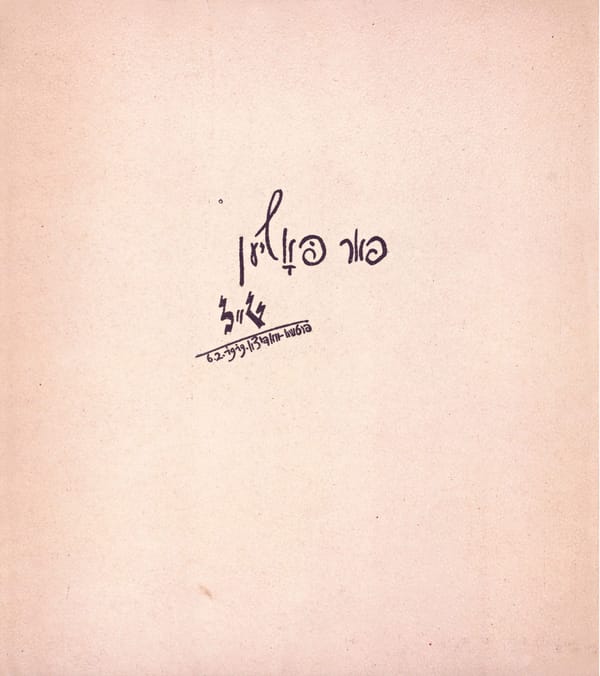

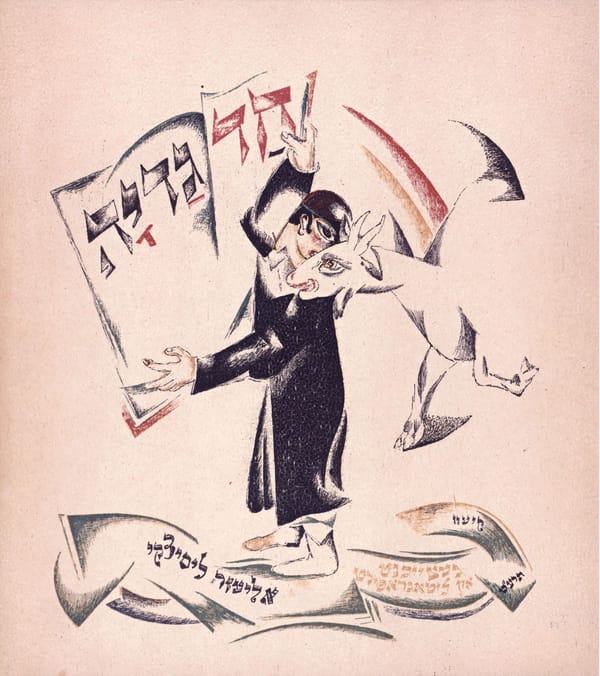

ICONOGRAPHY DUST JACKETEXTERIOR The ornamental use of words and letters on this On the lefthand panel, the outside flap that the panel—the variations in placement, color, size, and reader would have seen first, HH1 IV} (Had gadya) style—points to Lissitzky's growing interest in is printed in stylized Hebrew letters. "Had gadya" typography as design. was an Aramaic term that was absorbed into In the offwhite triangle on the center interior both Yiddish and Hebrew. The center panel, or panel are the Hebrew letters yud yud, a common the back of the dust jacket, bears a logo, most shorthand for the tetragrammaton, yud, heh, vav, likely the printer's, and the price, ten rubles. On heh, a biblical name for God that is not supposed TITLE PAGE the righthand panel, the inside flap, is a circular to be pronounced. By stylizing the yuds and plac In his opening image, Lissitzky symbolically links stamp depicting a man, a small boy, and a large ing them adjacent to each other, Lissitzky treats the central character of the song, a young goat, animal: the man is holding an object similar in the two letters as a single graphic symbol that to a Jewish boy who holds in his hand an open shape to the spice box used in the ritual of hav merges with the surrounding abstract geometric book displaying the title of the song. The over dalah, the ceremony marking the end of the shapes. That Lissitzky's letters form both a word lapping faces of these two kids—each provides 1 the other a second eye—strengthen their connec Sabbath. The words in the stamp are PI'? mC3*?1p and an element in the overall design implies not (Kultur Lige), the publisher of Lissitzky's Had only a respect for the sacredness of God's tion as one being. gadya. Both the lettering and the graphic sensi name—the letters suggest the name as much as On the banner underneath the boy's feet are bility of the drawing in the stamp suggest that it they express it—but also an acknowledgment of the publication details and the artist's name: the , was designed by Lissitzky. God's omnipresence. words aTa*rUNB'7 J1K flJrrXPI (drawn and litho Lissitzky incorporated stylized Hebrew letters graphed) are in yellow print, with the place of pub DUST JACKETINTERIOR as well in the righthand panel. In the triangle at lication, llP'p (Kiev), above and the date, arm All ten verses of the song are printed on the the top of the page are the lamed and the yud that (1919), below, both in black print. To the left of the lefthand interior panel of the dust jacket. In pink refer to the first and last letters of his surname. boy's feet, also in black print, is Lissitzky's Hebrew cursive at the top is the title, and directly below, The pair of triangular diacritical marks between name, rpro*? TTP^K. in bold Yiddish, is the first verse of the song: the letters tells the reader to read them not as a p^pa^t « "iK3 POKO TPI aanppKthe word but as individual letters. In the circle below father bought for two zuzim a kid). The subse is the name of the publisher, Kultur Lige, and a quent verses, all in Yiddish, are set in two surname, Kentzianavski, perhaps the name of the columns. Each verse builds upon the last, adding actual printer. a new line ("Then came the cat and devoured the kid") to the preceding verse ("That the father bought for two zuzim"). The phrase P'PPRX VIII (the kid) cascades down the left side of each col DEDICATION PAGE umn, graphically expressing the way that the The large cursive writing on this page is a dedi individual verses are chained together. In the cation— pr/ica Ilea (To Polyen)—though the identity lower lefthand corner of the page, just below of the dedicatee is a mystery to Lissitzky scholars. the final verse, the chain is completed: two of Lissitzky signed and dated this page as well: his these phrases are joined together to form a circle. initials alef and lamed (*?K) appear above the

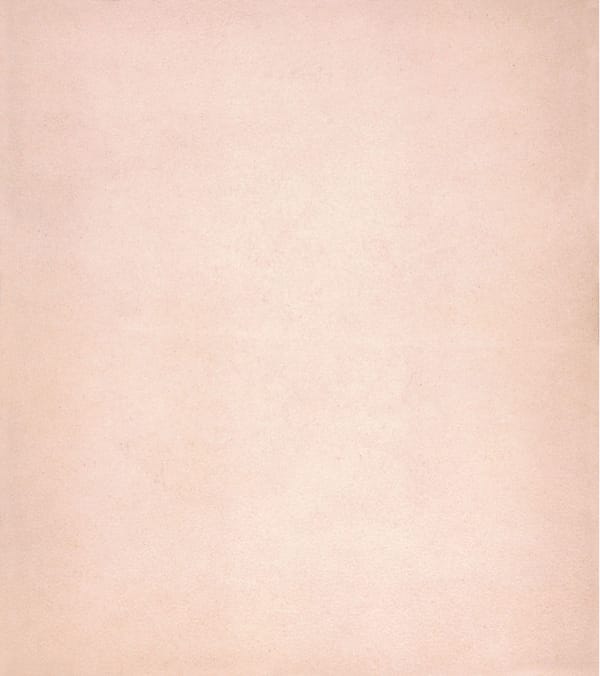

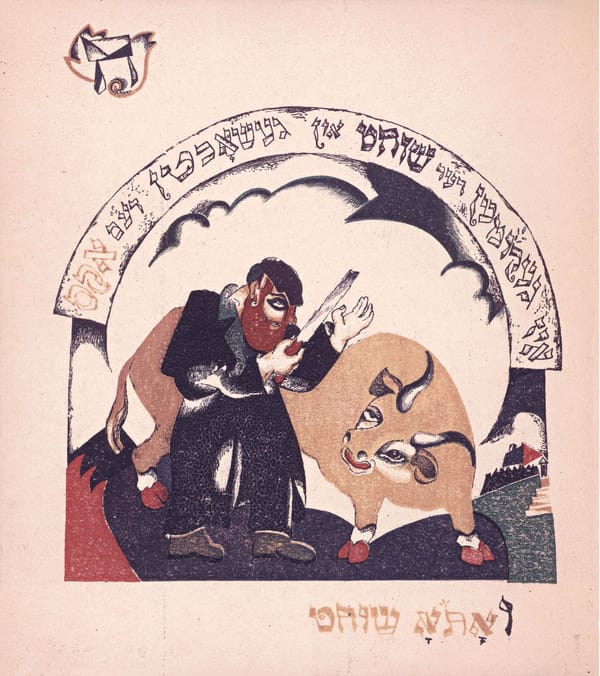

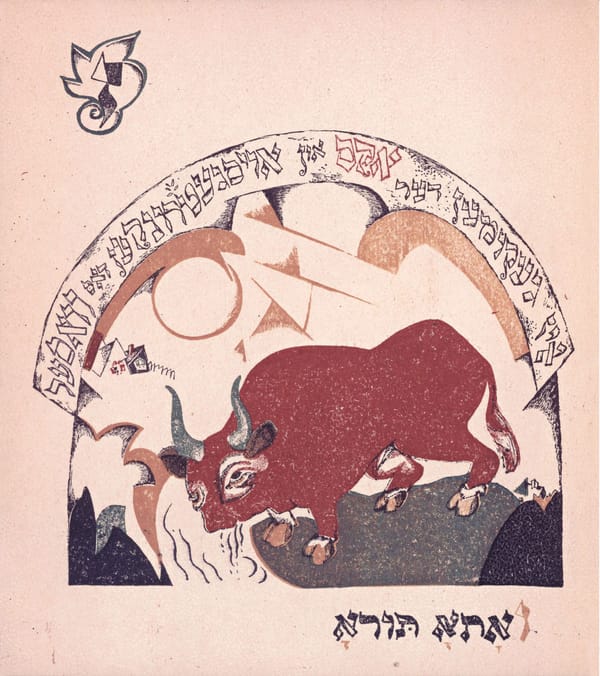

diagonal line; below are the date, written in Arabic God's promise to Noah after the Flood never again will change from black to orange in the following numbers, and a placename, probably Pushcha to curse mankind. Other images on this page antici illustration—Lissitzky will repeat this variation in Vodytsya, which is located just outside of Kiev. pate the action of later verses: the tiny red cat in his depiction of the ox in the later verses. the lower righthand corner is the central charac ter of verse 2, while the well behind the boy's back figures in verse 4. The image of the Jewish shtetl, the clump of houses drawn in the lower lefthand corner and also underneath the red cat, recurs repeatedly, and with varying significance, throughout the book. VERSE 1 VERSE 4 Each illustration is crowned with an architectural Though Lissitzky gives a distinctive treatment to frame containing the Yiddish verse. Through the the word ]Vp9QW (stick) in this verse, "Then came use of color, Lissitzky keys the text to the illustra the stick and beat the dog," he does not color tion below, perhaps in an effort to make it easy for code it to the figure in the illustration below. In the young reader to match word to figure. As we addition to the shtetl imagery flanking the dog, have seen, in this first verse, "The father bought there is an image of a figure either pushing or for two zuzim a kid," the green of the word PQ8Q VERSE 2 running toward what appears to be a broken (father) matches the green of the father's face, The action of the second verse, "Then came the shadoof, an ancient counterbalanced device used while the yellow of the word P^PPX (kid) matches cat and devoured the kid," is viewed from above for hoisting water. The bucket that would have the yellow of the kid. (Zuzim were silver coins; each by an eye set within a green circle. We will see a been attached to the nowdangling rope is mis zuz was worth a quarter of a silver shekel.) more detailed and conspicuous instance of this sing, but curiously the same rope seems to dangle Below each illustration is a phrase from the image in the final verse of the song. The red cat from the end of the stick, suggesting some sort original Aramaic version of the song. With the (f8p), the first murderer in the song, evokes Cain, of connection between the two objects. Given exception of the phrase under the first illustra the first murderer in the Bible. Lissitzky's tendency to foreshadow the action of tion, 828 pan (that father bought), all the Aramaic In the folio, bet (1), Lissitzky drew a small later verses, it may be that the smoky blue of the phrases are structured identically: 8U1B? 81181 figure, perhaps the dog from the next verse. clouds (and also of the word "stick" in the arch (then came the cat), 83^3 8TI81 (then came the None of the remaining folios contain the kind of above) is a visual hint of the fire that will soon 1 burn the stick. The connection between the well dog), and so on. The Aramaic vav (l), from the figurative decoration seen here and in the previ biblical waw, can mean either "then" or "and." ous illustration. and the stick, then, might be the water that will To mark the progression of the pages, subsequently quench the fire. Lissitzky placed decorative Hebrew letters in the upper lefthand corner of each page: these letters can be read simply as letters or as numbers, since each letter in the Hebrew alphabet possesses a numerical value. Note the small goat that Lissitzky drew in the alef (8) above the first verse, perhaps a flourish meant to underscore the goat's central ity in the song. VERSE 3 Lissitzky's illustrations are unified not only by Visually uniting this verse, "Then came the dog the repetition of these compositional and typo and gobbled up the cat," are the spikes that we IX graphical elements but also by the repetition of cer see on the teeth of the dog (TJin) and on the men tain images. In the above illustration, for example, acing ridges of the hills in the background. It is the rainbow echoes the rainbow glimpsed on the interesting to note how Lissitzky varies the colors inside cover, though here it assumes more promi of the animals from verse to verse: for instance, nence—traditionally, the rainbow is a symbol of the cat is now green instead of red, while the dog

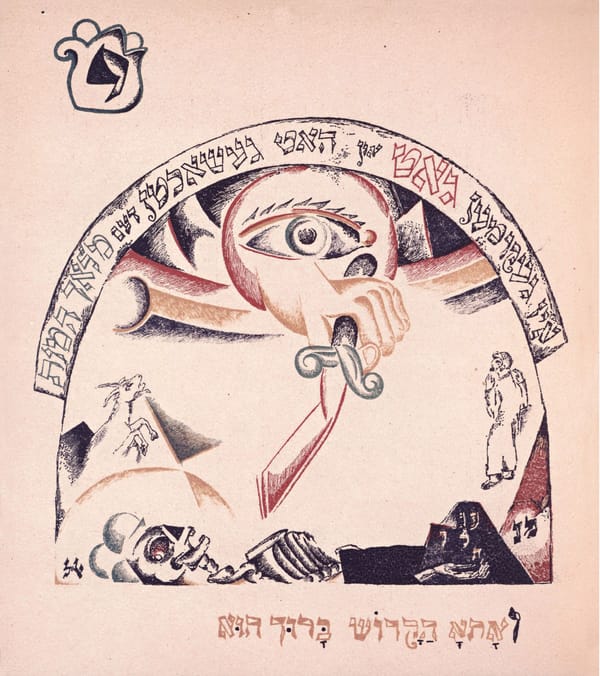

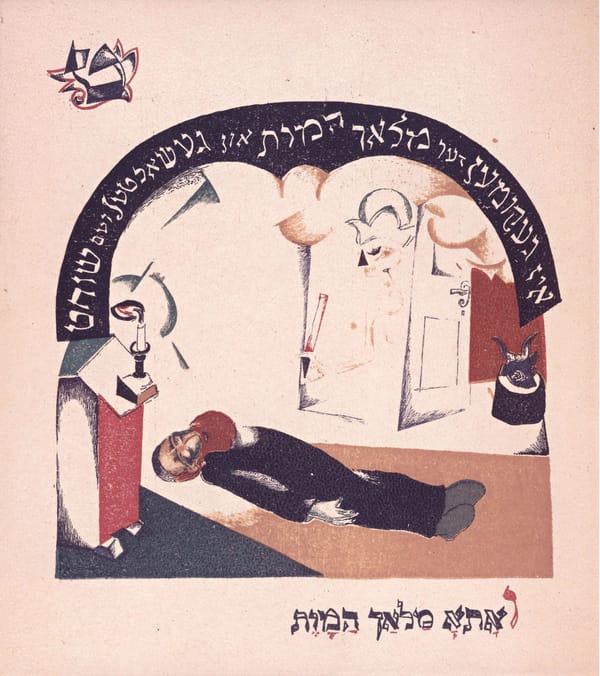

angel of death, TIIDn ^*?D (mal'akh hamavet), is used in Yiddish as well as Aramaic texts. The angel of death appears in a doorway wearing a green crown, most likely a reference to the Russian mon arch, and holding a sword in his right hand, a tradi tional image based on biblical descriptions and on the folk belief that the angel of death killed his vic VERSE 5 VERSE 7 tims with a sword dipped in poison or gall. The Drawing on a contemporary Yiddish phrase for Note that in the illustration of this verse, "Then candle burning above the shohet's head probably arson, |XH "l^OTI N (a red rooster), Lissitzky vividly came the ox and drank the water," Lissitzky intro refers to the Jewish custom of placing a lit candle represents the action of this verse, "Then came duces no ancillary images other than the shtetls at the head of a deceased person. the fire and burnt the stick." The shtetl now occu on either side of the ox (OpN). pies the foreground, and the stainedglass win dows to the left of the rooster identify the central structure as a synagogue (these same windows appear in the lower lefthand corner of the previ ous illustration). There are striking compositional similarities between this image and a painting by Issachar Ryback, entitled The Old Synagogue (1917; TelAviv Museum), made after the expedi VERSE 10 tion that Lissitzky and Ryback took in 1916 to VERSE 8 In terms of both its text and its imagery, Lissitzky's 2 study the synagogues of Ukraine. The fire ("1P"D) With the exception of the small shtetl in the lower final illustration is complex. For example, in the that burns the stick in this scene also burns the righthand corner, Lissitzky limits his imagery here verse above the illustration, Lissitzky uses the buildings, a reference to the burning of synagogues as well to the figures mentioned in the verse at Yiddish word 0*O (God), while in the Aramaic and Jewish towns in the pogroms of the late nine hand: "Then came the shohet and slaughtered the below he uses the traditional Hebrew phrase teenth and early twentieth centuries. ox." The shohet (fllTO), or slaughterer, is a person «m ira wnjm (the Holy One, Blessed be He). trained to butcher animals and birds according The letters in the lower lefthand corner of the to Jewish law. Originally a Hebrew word, "shohet" page are Lissitzky's initials—printed almost identi was universally recognized and was used in both cally to those on the dedication page—and the Yiddish and Aramaic. Thus, the word for "shohet" letters in the lower righthand corner are pe nun is the same both in the Yiddish verse and in the 02), an acronym for the Hebrew words "poh Aramaic phrase at the bottom of this page, NJ1N1 nikbar" (here lies buried). The letters in the angel anittf (then came the shohet). of death's hand are illegible. Many of the images in Lissitzky's illustration VERSE 6 of the final verse, "And the Holy One came, Lissitzky's choice of a giant colorful fish to depict Blessed be He, and slew the angel of death," are the action of this verse, "Then came the water and familiar to us: the kid and a bearded man, perhaps quenched the fire," brings to mind the sea ser the father or perhaps a more mature version of pent Leviathan, a biblical symbol of the forces of the young boy from the opening scene, now gaze evil. Lissitzky's fish, however, has a beneficent upward in awe as God kills the angel of death; the quality that may reflect the Jewish belief that the rainbow reappears, now spanning the entire sky; X meat of the Leviathan is the reward in heaven for VERSE 9 and the eye that earlier observed the cat devour the righteous. The burning synagogue from the This is the only time that Lissitzky deviates entirely ing the kid is now clearly the allknowing eye of last illustration is now absent, and the fire—even from his system of color coding. In this case, the God. This depiction of God is striking given the in relation to the small figure carrying the two verse, "Then came the angel of death and butch antiiconic tradition in Judaism. However, repre buckets of water ("120*01), an echo of the figure ered the shohet," is printed in white on a black sentations of God are commonly found in illumi from verse 4—is quite small. ground. Like "shohet," the Hebrew term for the nated Haggadot, and in several examples from

the eighteenth century we find instances where suggests that the oppressive czarist monarchy, 2. For a discussion of the phrase "a red rooster" and God is depicted similarly, through either an eye or symbolized here by the crowned angel of death, the painting by Ryback, see Haia Friedberg, "Lissitzky's Had Gadia'," Jewish Art 1213(198687): 29899. 3 was rendered powerless in the face of revolution a sword set within a circular cloud or sunburst. Still, there is a forcefulness to Lissitzky's image ary justice. 3. For examples of these images, see Emile G. L. Schrijver that can be ascribed to a more contemporary and Falk Wiesemann, eds., Die Von Geldern Haggadah und Heinrich Heines "Der Rabbi von Bacherach" (Vienna: influence: on the first Soviet stamp—with which NOTES Verlag Christian Brandstatter, 1997), pi. 26r; and Haviva Lissitzky certainly would have been familiar—an 1. It is interesting to note that in many of the words in the Aramaic PeledCarmeli, Illustrated Haggadot of the Eighteenth Century, phrases, Lissitzky represents the vowels as if he were writing in exh. cat. (Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 1983), pis. 10511,107,117. outstretched hand underneath a circular sun Yiddish. For example, in the word WW (came), Lissitzky positions grips a sword.4 The conflation of the hand of the vowel point under the final alef, rather than under the preced 4. For an illustration of this stamp, see Friedberg, "Lissitzky's God with the hand of the Soviet people implies a ing consonant ta\zWlK—as it would be in either Aramaic or Had Gadia'" (note 2), 302. Hebrew. Likewise, Lissitzky's word NQK (father) would be written divine component to the revolution; but it also in Aramaic as his word (cat) as xyw, and so on. VOCABULARY YIDDISH ENGLISH YIDDISH ENGLISH ARAMAIC ENGLISH HEBREW ENGLISH father devoured rrn "7n the only kid shohet bought dog i that mon T*ftD the angel of death for tOPBPaETTK gobbled up father Tra ttmpn the Holy One/ "TIX two stick P3T bought Kin Blessed be He 1 zuzim beat 1 then/and 2 a TP'*] fire came 1 3 kid burnt Him cat 1 4 came water dog n 5 NOTE n the (fern.) quenched KTOITT stick Translated here are the Yiddish, i 6 Aramaic, and Hebrew words—all TP! the (masc.) ox arm fire written in the Hebrew alphabet— T 7 that appear in Lissitzky's illustra an the (neut.) drank water tions. The use of Hebrew words in n 8 XI Yiddish and Aramaic texts is dis cussed above in the iconography cat slaughtered Him ox section, as is Lissitzky's treatment 9 of vowels in the Aramaic words. and God * 10

MUSIC INTRODUCTION VERSE 7. V'ata tora v'shata I'maya 10. V'ata hakadosh barukh hu Had gadya, had gadya 2. V'ata shunra v'akhal I'gadya d'khava l'nura d'saraf I'hutra v'shahat I'malakh hamavet d'hika l'khalba d'nashakh l'shunra d'shahat lashoheit 3. V'ata kalba v'nashakh l'shunra d'akhal I'gadya d'shahat l'tora d'shata l'maya REFRAIN d'akhal I'gadya Diz'van aba bitrei zuzei, d'khava l'nura d'saraf I'hutra 8. V'ata hashoheit v'shahat I'tora Had gadya, had gadya. 4. V'ata hutra v'hika l'khalba d'hika l'khalba d'nashakh l'shunra d'shata l'maya d'khava l'nura d'akhal I'gadya d'nashakh l'shunra d'saraf I'hutra d'hika l'khalba d'akhal I'gadya d'nashakh l'shunra 5. V'ata nura v'saraf I'hutra d'akhal I'gadya d'hika l'khalba d'nashakh l'shunra 9. V'ata malakh hamavet NOTE XII d'akhal I'gadya This transcription reflects the Sephardic v'shahat lashoheit pronunciation of the Aramaic lyrics to which 6. V'ata maya v'khava I'nura d'shahat l'tora d'shata l'maya many modern singers of "Had gadya" are accustomed. Lissitzky, however, would have d'saraf I'hutra d'hika l'khalba d'khava l'nura d'saraf I'hutra been familiar with the Ashkenazic pronuncia d'nashakh l'shunra d'hika l'khalba d'nashakh l'shunra tion. Here is the second verse transcribed as Lissitzky would have heard and sung it: d'akhal I'gadya d'akhal I'gadya "V'oso shunro v'okhal l'gadyo."