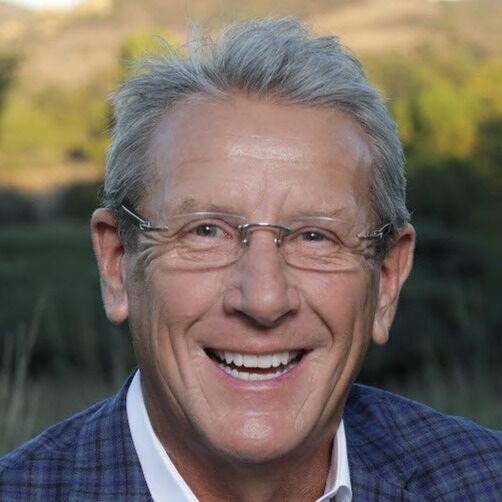

Dean Stoecker is a visionary leader and influential entrepreneur in the field of data analytics and business intelligence. He is widely recognized as the co-founder, Chairman, and CEO of Alteryx, a leading data analytics company that empowers organizations to transform data into actionable insights.

Under Stoecker's guidance, Alteryx experienced significant growth and innovation, pioneering a platform that democratizes data analytics and enables users across various industries to make informed decisions through intuitive analytics tools.

Key Takeaways

(02:13-07:00) Not working for the man but trying to be the man

(07:00-10:50) Make your content ubiquitous

(10:50-21:52) “Art of War” for business

(21:50-23:50) No one is ever going to love your idea

(23:50-32:27) Leaders are defined by how many leaders they create

(32:27-33:38) Analytics as a social experience

(33:46-40:18) Democratizing creative instincts

(40:18-46:00) Make products that are engaging

(48:28-52:40) On the democratization of data science

📱 Apple Podcasts | 🎧 Spotify | 🔗 iHeart

View the Episode's Podbook™

Empowering Innovation Through Data

Dean Stoecker’s entrepreneurial path has been shaped by a blend of personal experiences and business challenges. From his early days growing up in a family-run business to co-founding Alteryx, Stoecker’s journey is a testament to resilience, creativity, and the power of data.

His vision has not only transformed the analytics space but also reshaped how businesses approach data science and problem-solving. Stoecker’s story emphasizes the importance of listening to customers, fostering leadership, and creating products that empower individuals to solve complex challenges while improving their personal lives. Through Alteryx, he has revolutionized how companies use data, making it accessible and impactful for users across industries, from sports to banking and beyond.

1. Not working for the man but trying to be the man

Dean Stoecker grew up in a family-run business and, as a young kid, witnessed the challenges his father faced, such as customers who wouldn't pay or vendors who wouldn't sell. Although these struggles made him question starting a business, he also recognized the rewards his father experienced. This early exposure to entrepreneurship influenced him greatly, and when he co-founded Alteryx, all three of the founders had grown up in entrepreneurial households. Despite starting his first business ventures later in life, at age 40, Stoecker believes he could have succeeded sooner, reflecting that he would tell his 25-year-old self not to wait to start a business.

Before Alteryx, Stoecker launched a few entrepreneurial ventures, including Sensible Socks, which he thought was a great idea but failed due to challenges in packaging and marketing. He also ventured into a chimneyless fireplace business, which lost him a quarter of a million dollars. Despite the setbacks, these early ventures taught him important lessons in business, such as the importance of controlling the supply chain and understanding the complexities of marketing. With over 20 years of experience in the data and analytics space, Stoecker founded Alteryx in 1997, drawing from his previous work with content companies and divisions of major firms like AC Nielsen and Dun & Bradstreet.

It turns out that when we started Alteryx, all three founders grew up in entrepreneurial households. I don't know if it's the DNA, but clearly, there is the influence that gets you excited about not working for the man but trying to be the man, change the world, get creative, and do different things.

— Dean Stoecker

2. Make your content ubiquitous

Dean Stoecker learned that to maximize the value of content, it must be made ubiquitous. In software, this means creating an easy-to-use and engaging interface, making people want to interact with it. Then, adding analytic layers helps turn raw data into meaningful insights, leading to better stories and outcomes. From his experience with various companies, Stoecker noticed a common mistake: while they recognized the importance of data, software, and analytics, they spread their investments too thinly across all three, which led to mediocre results. This realization led him to found Alteryx, focusing on creating a platform that was data-agnostic, analytic-agnostic, and industry-agnostic, to make it so engaging that millions of “citizen data scientists” would use it to solve business challenges.

The journey to creating Alteryx was a long and emotional one. Stoecker describes it as a "long emotional journey to creating something great," which was not without its struggles. In his book, The Masterpiece, he refers to difficult phases as “The Valley of Despair” and “The Swamp,” reflecting the challenging moments of the startup. One of the key strategies Stoecker used to create the perception of a larger, more stable company was inspired by the ancient quote, "All warfare is based on deception." For his first big deal, he threw a party complete with a Mariachi band and invited potential customers, creating an impression of a well-established company. Additionally, he crafted a user experience walkthrough of the software even before it was fully developed, which helped build customer confidence and show that Alteryx was already thinking about their success. This strategy was crucial in building momentum for Alteryx's growth.

And what I learned is that in order to maximize the value of content, you have to make it ubiquitous. And the only way ubiquity happens in software is if you wrap that software in an easy-to-use, engaging interface that makes everyone want to play in the space. And then you had to apply analytic layers on top of it to make the data dance, to tell better stories, to get better outcomes.

— Dean Stoecker

3. “Art of War” for business

Dean Stoecker emphasizes that entrepreneurship is a long and unpredictable journey, often full of challenges and setbacks. He believes that every entrepreneur should read The Art of War for its valuable business lessons, particularly the importance of balancing strategy and tactics. Stoecker's early days with Alteryx were self-funded, and to win his first major deal with Money Mailer, he created the illusion of a larger, more established company by hosting a Mariachi band and an interactive presentation for the client. This creative approach helped him secure the deal, marking a significant turning point for Alteryx.

Stoecker reflects on the personal and business struggles he faced, including a difficult divorce and the decision to potentially sell Alteryx. A conversation with a mentor helped him shift his mindset to "go big or go home," which led to 14 years of bootstrapping before finally seeking outside investment. Throughout his journey, Stoecker learned that business success, like in life, is not linear. It requires resilience and the ability to adapt through difficult times such as the dot-com bubble burst, 9/11, the 2008 financial crisis, and COVID-19. His story underscores the importance of persistence and the pursuit of greatness, both professionally and personally.

It struck me pretty clear that we all just want to create something great. We all wanna create a great family, great marriage, great friendship, great education, have a good job, and if you're as lucky as me, it's starting a business.

— Dean Stoecker

4. No one is ever going to love your idea

Dean Stoecker shares that entrepreneurs often become deeply attached to their ideas, believing them to be the best, and that no one will love their idea as much as they do. When mentoring startups, he advises that financial support typically comes not because people love the idea but because they recognize a pattern of success. Stoecker likens the entrepreneurial journey to nurturing a child, noting that while the journey may take years, it is incredibly rewarding. In his case, the "baby" of Alteryx took 24 years to fully deliver but became something he cherished deeply.

Alex Shevelenko acknowledges the privilege of working with someone like Stoecker, whose values and vision shaped the company. The admiration for Stoecker's dedication and the nurturing of Alteryx as a reflection of his values highlights the deep commitment he has to the company and its people.

When I mentor for startups, I tell them no one is ever going to love your idea as much as you. So, even if you get financial support from people, it's not because they love your idea but because they believe in a pattern recognition that they've seen before.

— Dean Stoecker

5. On the democratization of data science

Dean Stoecker shares how paying close attention to customer feedback has been crucial for the evolution of Alteryx’s platform. He highlights how, through listening to customers like Walmart’s finance team, the company expanded its toolset by integrating financial formulas. This kind of responsiveness allowed the platform to grow in ways that addressed unforeseen use cases, like those in industries such as oil, banking, and airlines. For example, Alteryx’s ability to predict when to shut down an oil rig or hedge fuel costs for airlines demonstrates its wide-ranging impact in saving millions of dollars. Additionally, the platform's use in the sports industry, by teams like the Green Bay Packers and Dallas Cowboys, and in automotive design with McLaren, further illustrates its versatility.

He emphasizes that the most rewarding part of Alteryx’s journey is the real-world impact it has on individuals’ lives. He finds it gratifying that the platform, which initially focused on solving complex business challenges, ultimately helped users save time and improve their quality of life, with some saying they now have more time to spend with their families. This unintended yet powerful outcome reflects the broader, human-centered impact that Alteryx has had, not just in business but in changing the lives of its users for the better.

You have to pay attention to what your customers are doing and saying about you, your product, and the outcomes that they get. It's the only way you're going to figure out how to alter your product or platform to make it more immersive or to extend its capabilities to be able to solve things you never heard of.

— Dean Stoecker

Other Episodes

Godard Abel | CEO of G2

S 01 | Ep 6 Where You Go for Software: Reach Your Peak

Peter Fader | Co-Founder of Theta CLV

S 01 | Ep 10 Turning Your Marketing Into Dollars