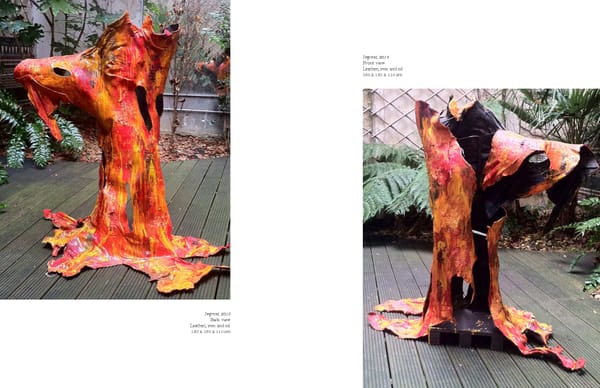

35 34 Imprints of absence About the works of David Cohen Masks, canvases, sculptures, casts, but also leather, olive wood, jute bags, those used by the post office, bronze, ceramics, bones, lianas, or steel, to name but a few of the ways and materials at play: David Cohen’s works are di- verse, his techniques are plural, his effects are surprising. Something seems to insist through repetitions, changes, variations, as we say of musical variations. Something ? What? A thing ? The Thing - «das Ding» - in the sense of Freud in his Sketch, when he brings up this term to designate what is distinct from any object 1. The Thing lies beyond perception, it points towards what is incompre- hensible, elusive and unassimilable in the object 2. Traces left by the experience, traces of the object, traces of absence: that’s what remains in memory. The memory is made of mnemic traces, that is to say, a profusion of absences always present. What is no longer will always be. What constitutes memory is what is no more. This is the paradox of memory. It is also the paradox of David Cohen’s works which turns what has disappeared or – in the process of disappearing – into footprints. These imprints of life beyond the object, of the object’s inertia pursues through him a journey beyond what it is. Thus this work leads whoever encounters it beyond what is shown, beyond the objects exhibited. To elevate the object to the dignity of the Thing, it is indeed the work of sublimation: it is moreover the definition that Lacan gives, building from the Freudian Thing, this “beyond object” that conceals the object. An object that must be found, an object that is thought to be lost but “which has never really been lost, even though it is essentially a matter of finding it” 3. This is perhaps what the work of memory does: to find what has not been lost beyond what is no more. One could say that David Cohen, be- tween traces and imprints, exposes the objects of memo- ry: multiple objects, various, combined, recombined, lost, found, which each in their own way exposes this Enig- matic Thing that escapes us. The impression left by the works of David Cohen is that, through them, he tries to capture this elusive, to get the impression, to graze the memory, to capture the trace through painting, sometimes carving it, or wrap- ping it, grasping its shape, through a material, by the effect of a color. Whatever the means used, what he aims for is the imprint of absence, the presence of absence. This is what gives a unity to the diversity of his produc- tions: enabling us to encounter them as infinite varia- tions as on the same theme. David Cohen’s works revolve around the tension be- tween loss and memory. Between traces and footprints, it is the loss that torments his works. But that›s also what gives them their momentum. He finds life in the object, he gives life to lost objects. David Cohen runs after the trace: that is what gives life to his creations. This is why his quest is never ending, like memory, which always reveals the infinity of what could have been lost, of what could have disappeared forever, which, perhaps, has even been forgotten. Faced with disappear- ance, in the face of oblivion, there is no other solution than creation. We create from loss, forgetfulness, ab- sence, even if we show the absence present in what we show. What the course of his work reveals is that we do not find the object: we find it, but it is always another object. Hence the insistence of series, pictorial or sculp- tural, that he composes. Through his work as an artist, what happens is the temptation of life beyond loss: everything happens as if David Cohen was trying to revive what has been lost, what has become inaccessible, to what is dead. To find the imprint of life, to make memory come alive, to animate the inanimate, to give life to matter, to bring out the life, whether it is through a canvas or a vegetal left- over. Bring a dead tree to life and have it carry another life. To make traces come to life, through footprints, making them visible, molding them: this is the work of memory that David Cohen devotes himself to, reviving what has been lost, to show life beyond death, beyond abandoned remains. Giving a memory of forgetfulness, beyond oblivion. A trace is what the object leaves once gone elsewhere, like the footprint of Friday in the sand. For Robinson Crusoe, this is the sign that there was someone who left somewhere else, who was alive even though maybe he is no more. And indeed, the memory is made of traces of what has been. Thus memory is continuity and disconti- nuity. Is a memory trace a sign of something that is no longer or something that is always? In any case, David François Ansermet Cohen›s perspective is to give life to these traces, to find their shape, to make an impression of it, to wrap their contours, to grasp their life beyond what rest. To revive what is no longer, to me this seems to be David Cohen’s perspective in his poetic works, which are indeed the fabrication of life from different inanimate materials. This doesn’t happen by itself. Beyond memory and its footprints, joy is there first and foremost: it is what is most evident in his productions - as in his personality for those who know him. A certain exaltation, far from convention, free of codes, including those of his other profession, that of professor of child and adolescent psychiatry. This joy is what allows the transmission. And that is also what is transmitted. It is passion to transmit that bring together his art, his teaching and his clinical work. The challenge is to pass on what escapes, including what cannot be captured through representation: to catch up urgently, with insistence, to capture its imprint, by any means whatsoever, to make visible the invisible, the life in all things – by elevating every object, everything remain, every trace, to the dignity of the Thing. Make the imprint of the Thing. Give an appearance to what is beyond what is lost, give it substance, realize the ap- pearance in substance, preserve its memory: such is the perspective of David Cohen around an object still lost but always to be found, unendingly. François Ansermet psychoanalyst, Honorary Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University of Geneva and University of Lausanne, Member of the National Consul- tative Committee of Ethics in Paris, Vice President of the Agalma Foundation in Geneva. For years, he has dialogued with artists and performers about changes in society and human condition, but also on how these changes occur (by the work of memory? Of chance?). His last dialogue with Prune Noury in Serendipity is a profound testimony of his commit- ment with artists. 1. « What we call things (Dinge) are remnants of judg- ment »: Sigmund Freud, Sketch of a Psychology (Entwurf einer Psychology), trans. S. Hommel et al., Toulouse, Érès, 2011, p. 91. 2. « Das Ding » is indeed defined by Freud as a non-assimila- ble part, distinct from the known part of the object, cf. Ibid, p.147. 3. Jacques Lacan, Le Séminaire, Livre VII, « L’éthique de la psychanalyse », 1959-60, Seuil, Paris, 1986, p. 72.

In Your Head Page 15 Page 17

In Your Head Page 15 Page 17