The Hidden Secrets of Customer Lifetime Value

Learn how an increase in sales could harm your business and much more

What is Customer Lifetime Value and Why Is It Important?

Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) attempts to determine the economic value a customer brings over their "lifetime" with the business. At the heart of understanding CLV lies the recognition that a customer does not represent a single transaction but a relationship that is far more valuable than any one-time exchange.

However, CLV is not about any one customer; it is about stepping back and taking a look at your customer base as a whole - understanding that while some never return and some never leave, on average there is a typical customer lifetime and that lifetime has a specific economic value.

Understanding Customer Lifetime Value is incredibly important for customer service professionals and for businesses of all types. Why?

Because if you don't know what a client is worth, you don't know what you should spend to get one or what you should spend to keep one.

For instance, if it costs you $100 to acquire a customer, and your customer's CLV is $75, then we've got a problem Houston.

Understanding CLV allows you to drill down and understand the economic value of each customer, so you can make sound decisions about how much to invest in acquisition and retention.

Why a Non-Geek Guide to Customer Lifetime Value?

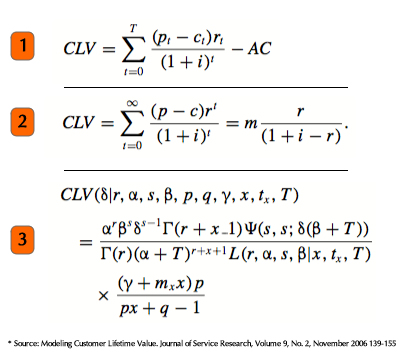

The Customer Lifetime Value calculation can be an extremely complex undertaking. Both correctly identifying the underlying components and calculating the end result have been the focus of numerous academic studies. To say that it can be complicated would be an understatement. Here are three examples of CLV calculations from the academic literature.

While anyone with a graduate course in finance or statistics can probably hack their way through the first two formulas, the third looks like something pulled off one of the whiteboards from the set of The Big Bang Theory. I've been exposed to some fairly daunting business math in my day, and if I had been shown the last formula out of context I wouldn't have known if it was designed to calculate Customer Lifetime Value or the quantization of energy.

So, if calculating Customer Lifetime Value is so mathematically challenging, do we have to go full geek to effectively use CLV in our businesses?

So, if calculating Customer Lifetime Value is so mathematically challenging, do we have to go full geek to effectively use CLV in our businesses?

The answer is no.

While it is wise to be cautious about using nonscientific evidence for analysis, often statistically sound approaches are not feasible. Whether due to budgetary, time, or data constraints, sometimes the back of the napkin is all we have.

Yet sometimes the back of the napkin is good enough. When people apply common sense and experience to non-scientific evidence, the process can often yield extremely positive results.

Much of the reason for this non-geek guide to Customer Lifetime Value is the understanding that, even if you don't whip out the slide rules and try to create a scientifically sound model, spending time on each component of the CLV model can be incredibly instructive.

Whether you are measuring the value of customers in your department, your small business, or even your blog, just thinking about CLV and its parts can help you refine your marketing and retention efforts.

Let's begin by taking a look at the major components of Customer Lifetime Value.

Calculating The Profit of an Average Transaction

The tendency when thinking about the lifetime value of a customer is to focus on the revenue the customer brings in over their lifetime. However, focusing on revenue will almost always overstate the value of the customer. The more accurate way to measure is to focus on what is known as the Unit Contribution Margin, which we'll call marginal profit for short.

Calculating marginal profit is simple in many industries. For instance, if a Starbucks customer buys a $5.00 latte, that transaction has costs associated with it. The milk, the cup, the coffee, the lid, and the flavoring all add to a variable cost that is incurred for that latte transaction.

Let's assume those costs are $1.50. It's obvious that if you wanted to calculate the Customer Lifetime Value of a Starbucks customer, you would want to use the $3.50 of marginal profit as your metric, not the $5.00 of revenue. Using revenue overstates what you made on the transaction. The true economic value of the transaction is $3.50.

Let's assume those costs are $1.50. It's obvious that if you wanted to calculate the Customer Lifetime Value of a Starbucks customer, you would want to use the $3.50 of marginal profit as your metric, not the $5.00 of revenue. Using revenue overstates what you made on the transaction. The true economic value of the transaction is $3.50.

The next step is figuring out the average of all of the company's transactions. Not everyone buys the $5.00 latte. Some buy the $3.00 muffin, others buy the $1.50 straight coffee. The trick for Starbucks is figuring out how many of each and calculating an average profit profile per customer.

In the end, Starbucks would hopefully come up with something like: the average Starbucks customer spends $4.30 at an average cost per transaction of $1.10 - thus the marginal profit for an average transaction is $3.20. (PS. All of these numbers are hypothetical.)

It is important to note that in this case, labor is not a variable cost. Ignoring anomalies like sending staff home on a slow day, Starbucks' labor is constant. They are paying the staff whether that cup of coffee is purchased or not. Thus, it does not contribute to marginal profit.

Labor would be included, however, if labor costs vary based on whether a service is performed or a product is sold. For instance, maid services that pay only per job or spas that pay per service performed. Product companies can also have variable "labor" per unit, if for instance, there are commissions paid on sales.

But I work for myself...

For consultants or solopreneurs, the calculation can be tricky. If your hourly rate is $50 and you provide 10 hours of service, $500 will be your revenue, and $500 will be your cost. How do you value the cost of your time compared to your hourly rate? My suggestion is to use opportunity cost.

The presumption is that you charge a different hourly rate yourself than you would presumably receive as an employee. Calculate what hourly rate you would be earning in an alternative employment situation and use that opportunity cost as the cost of your time. If you made $20/hour at your last job or you think that's about what you would get if you sought employment, then use that number as your cost.

Since your primary cost is the value of your time, you have to determine the opportunity cost of taking that hour away from other economic alternatives and spending it on that client. It might be a wild guess, but it can still be instructive.

What is Your Customer's Lifetime? (Customer Retention Rate)

To understand CLV, you must know the lifetime of your customer. Now, we will have to do a little math here, but it is just dividing a couple of numbers, so it still qualifies as non-geek.

Calculating customer lifetime can actually be fairly simple if you have the data. The first step is to calculate your customer retention rate, and then do some simple division to get your customer lifetime.

To calculate your retention rate, take the number of customers from last year who are still customers this year - that is your retention rate. If you had 100 customers last year and 45 are still doing business with you this year, then your retention rate is 45%. (For a more sound approach, you would want to track it over multiple years and take an average.)

Once you have the retention rate (RR), then it is easy to determine customer lifetime. Simply apply this formula:

In this case, CL = 1/(1 - .45) = 1.8 | Your customer lifetime is 1.8 years.

An important consideration is whether your business has time-bound contracts with customers. Mobile phone providers and fitness clubs will have different characteristics to consider when approaching this metric than businesses that don't have contract periods as part of their customer relationship.

The Last Piece is Your Discount Rate...

In non-geek, the discount rate is the interest rate you borrow money at in your business, and it is essential to knowing the true value of your customer's future cash flows. The concept is based on the time value of money, the premise that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow.

If the lifetime value of a customer is fairly short, the calculation, while methodologically sound, might not be material. However, if you have a long time horizon, the time value of money is a real consideration. To put it in perspective, would you rather have a $100 from your customer today or twenty years from now? Of course, we all know the answer to that. 20 years from now you'll be lucky if $100 buys you a ream of paper for your copier. (As if we'll be buying paper for copiers in twenty years!)

For our back of the napkin purposes, you are probably safe to ignore the discount rate in calculating your Customer Lifetime Value. Just understand that the longer you calculate your customer lifetime to be, the more important the discount rate becomes and the more inaccurate your model becomes when you ignore the rate.

Now That You Have the Parts: Understanding Customer Segmentation

At the heart of customer segmentation is the belief that all customers are not created equal and that understanding the differences among customer segments is key to effectively acquiring and retaining customers.

Depending on the nature of the business, customer segmentation can require some serious mathematical analysis to be done properly. However, in the spirit of our non-geek guide, we will approach customer segmentation by asking one simple question:

How would I group my customers if I wanted to customize my marketing, retention, or product offerings?

Customer segmentation can occur on many bases: demographic, psychographic, behavioral, and so forth. The key is knowing which breakdown is most valuable for your business.

The most logical first step is to break down the segments based on differentiated products or services. For instance, say your department provides support services both to small businesses and individuals. If the offerings to these two types of customers are distinct, you would probably want to segment your customer base into business customers and individual customers. In other words, you would calculate a Customer Lifetime Value for each segment.

The most logical first step is to break down the segments based on differentiated products or services. For instance, say your department provides support services both to small businesses and individuals. If the offerings to these two types of customers are distinct, you would probably want to segment your customer base into business customers and individual customers. In other words, you would calculate a Customer Lifetime Value for each segment.

If your business does not have obvious divisions like the one above, you should consider what factors have the most impact on customer buying characteristics - or segment on behavior itself. In the first case, you would simply ask yourself what impacts purchasing. Do men and women have different buying patterns? Is household income important to purchasing behavior? Is there a psychographic factor like "plays golf more than twice a week" that really differentiates activity?

Sometimes behavioral data, how the customer behaves with your business, is the best way to segment. Do you retain customers who buy your premium product at a significantly greater rate than all others? Is three purchases the magic number that makes a customer stick significantly longer? Do customers who remain after 9 months increase their average lifetime purchases by more than double?

As you can see, your ability to segment your customer base is directly related to what you know about your customers (or are willing to find out). However, in the spirit of our non-geek approach, let me advise you to start with your gut. If you know your business, you probably have an innate sense of what types of customers act what way. Try to fill in the blanks on this statement:

For example... Customers who are over 55 tend to retain longer. Customers who subscribe to the newsletter tend to have much higher average purchases.

Go with your instinct first, then dig into your data to try to prove or disprove your hunch.

Technically, the calculation of Customer Lifetime Value should include acquisition and retentions costs. To know a customer's true lifetime value, you need to subtract the cost to acquire and keep that customer. However, I find it helpful to calculate CLV without acquisition and retention costs. To me, this is the best way to isolate variables and to see their effect when using the back of the napkin approach.

This is similar to the EBITDA concept in accounting - figuring out your earnings before taxes, depreciation, and amortization. It gives you a sense of the purely operational figure, outside of the other inputs.

Let's start with acquisition...

What Are Your Customer Acquisition Costs?

Knowing what it costs to get a customer in the door is one of the most valuable pieces of information any business owner can have. Customer acquisition costs are generally the easiest of the metrics to compute. While each industry and business is different, the broad brush approach is simply to take your marketing expenditures for a period and divide by the number of new clients in the same period.

Try to find a period that is relevant for your business based on how you approach your marketing, and how much lag time there is in your business between marketing and acquisition. Don't forget hidden marketing costs such as loyalty or customer referral programs.

If you are a small business / solopreneur, you would need to measure time spent on blogging, social media, or content creation. If your web site and social media are your only sources of new customers, you would take the time spent on these items in a month, multiply it by your hourly rate, and calculate your marketing cost.

Whatever method is appropriate for your business or department, the goal is to figure out exactly what it costs to acquire a customer.

What Are Your Retention Costs?

If a customer stays with you, on average, for 2.5 years, what are you spending to keep them coming back? Most companies put money into retaining customers, and much of the focus of customer service and customer experience writing is about the retention of customers already acquired. Calculating these costs can be a challenge, because there is a much greater mixture of hard costs and soft costs in this area than are found in the marketing bucket.

Start with any obvious hard costs: perks for longevity, discounts for existing customer, freebies for certain buying behaviors, etc. These are the costs that can usually be calculated easily and accurately. When making the calculation though make sure to average the cost out across the entire customer base.

Start with any obvious hard costs: perks for longevity, discounts for existing customer, freebies for certain buying behaviors, etc. These are the costs that can usually be calculated easily and accurately. When making the calculation though make sure to average the cost out across the entire customer base.

In other words, if you gave $1,000 in longevity discounts last month, but only 25 of your 5,000 customers received the discount, you would still spread that cost across your entire database of 5,000, not just the 25 who received the discounts.

Soft costs are trickier. If you add a part-time person so that your manager can focus on customer outreach, is that a retention cost? If you send your sales staff to a customer service seminar, is that a retention cost? If you redesign the help section on your web site, is that a retention cost? While it can be difficult to determine how to treat soft costs when looking at retention, it is well worth the time to evaluate.

One question that should help determine if a soft cost belongs in the retention "bucket" is this: what is our primary reason for incurring these costs? If customer satisfaction, retention or any similar customer service-based sentiment is the primary reason, it is probably safe to consider the expenditure a retention cost.

A final note on acquisition and retention: If you are segmenting your customer base, you will need to apply these calculations for each segment, not the customer base as a whole. In fact, these acquisition and retention analyses truly show their power when applied to meaningful customer segments, as you will see when we begin...

Now that you have your CLV and a grasp on your marketing and retention costs, it is time to start putting the two together. Even when taking the scientific approach (which we are not), this part of the process can involve a good bit more art than science. A few extremely hypothetical (and yes, very simplistic) examples will hopefully get the wheels spinning on how to approach this final phase in your specific situation.

While we are only going to break down acquisition and retention, there is a third strategy that is important to bear in mind: customer expansion. Instead of purging customers with low or negative CLVs, you attempt to expand your business with them and help them become more valuable customers.

Example 1: Customer Lifetime Value and Acquisition

A suburban golf pro shop determined that their customer base broke down quite naturally by geography. The pro shop determined that most of their customers came from two zip codes, one to the east and one to the west, and accordingly, the pro shop decided to calculate the CLV separately for each zip code. What they discovered was that the CLV for the east customers was 4 times the CLV for the west customers.

Once they dug into their stats, they found out how important this differentiation was. The east zip was 30% of their customer base but 80% of their profit. The west zip represented 70% of their customer base and 20% of their profit.

The pro shop had been spending their marketing dollars evenly east and west. Even though they knew the customers from the east were more valuable, they continued to put 50% towards the west because it seemed more effective. They were simply getting a much better "response" from the west marketing. Calculating the CLV for each segment made it obvious that the marketing dollars were not being allocated effectively.

Example 2: Customer Lifetime Value and Retention

A chiropractor instituted a Chiro-Bucks rewards program to help retain patients. Patients could earn points for various activities, from receiving services, filing their own insurance, or referring other patients. These points translated into straight dollars off. After a year using the points program, the chiropractor found that it was being used heavily and, when averaged out among his entire customer base, represented almost 10% of CLV.

Unfortunately, the increase in retention since starting the program (other factors assumed constant) had only been 2-3%. What the chiropractor found is that Chiro-Bucks had not extended the life of the majority of customers; most tend to use chiropractic until they no longer need it or insurance no longer covers it. The Chiro-Bucks had simply helped keep some people that previously would have defected to another chiropractor due to dissatisfaction with the service, the majority of whom could probably be saved by implementing better service systems. Understanding CLV had enabled this chiropractor to see that the Chiro-Bucks program had a cost far greater than its long-term economic value.

Of all the many exercises in a business, computing Customer Lifetime Value can be one of the most eye-opening and rewarding. Hopefully, the point has been well-made by now that knowing the lifetime value of your customers can help you truly understand the value of your marketing and retention expenditures.

The goal of this post was to provide a detailed look at a broad brush approach to CLV - to address how to think about Customer Lifetime Value as much as how to calculate it.

What should you takeaway from this post? Hopefully, that you can derive true value from a back of the napkin approach to CLV, but that you should realize the limitations of using such a non-scientific approach. Each business is different, but there might be a time where you feel the need to get your geek on. If so, below are some resources for further exploration of Customer Lifetime Value.

Customer Lifetime Value Calculator and Resources (i.e. Getting Your Geek On)

If you have questions or comments about anything in this post, please share them in the comment section below or feel free to .

Roy Cardiff runs a mail-order business that tracks sales to each customer. He recently decided to cut costs by curtailing catalogs to those customers who are least likely to buy from him in the future.

His customers break down into three categories: those who made several small purchases throughout the past year; those who made a single purchase but for a much larger amount, and those who have had a long but sporadic relationship with his firm.

Which segment of customers should Smith prune from his mailing list?

According to several Wharton marketing professors who have studied this issue, there is no easy answer, despite new and increasingly sophisticated efforts to measure what is called "Customer Lifetime Value" (CLV) - the present value of the likely future income stream generated by an individual purchaser.

"For many companies, their whole business revolves around trying to understand which customers are worth keeping and which aren't," says Wharton marketing professor Peter Fader, who used the mail order example above in a recent co-authored paper entitled, Biases in Managerial Inferences about Customer Value from Purchase Histories: Intuitive Solutions to the Mailing-List Problem. "This has led managers from a broad cross section of industries to seek out more refined measures of CLV, using data-intensive procedures to identify top customers in terms of their likely future purchasing patterns."

The goal is not only to identify customers, but to reach out to them through cross-selling, up-selling, multi-channel marketing and other tactics - all of which are tied to metrics on attrition, retention, churn and a set of statistics known as RFM - recency, frequency and monetary value.

"CLV is a hot area," notes Wharton marketing professor Xavier Dreze, co-author of a new paper entitled, A Renewable-Resource Approach to Database Valuation. Although CLV is by no means new - it has long been used in business markets dealing with large key accounts - the concept has been energized by the increasing sophistication of the Internet "which allows companies to contact people directly and inexpensively." CLV, Dreze says, "sees customers as a resource [from whom] companies are trying to extract as much value as possible."

Yet many companies are discovering that CLV - which is one component of Customer Relationship Management (CRM) - remains an elusive metric. First, it is hard to calculate with any degree of certainty; second, it is hard to use.

"The only number a manager can have much confidence in is a customer's current profitability," says Wharton marketing professor George Day. "And the basic question becomes, now that you have that data, what are you going to do with it? Some companies use this information to create different programs for different value segments. In the financial services industry, for example, customers get different levels of service depending on how big an account they are. But there is always the risk that by doing this you anger other customers."

In addition, it's hard to predict how long a customer will stay with the company or how 'growable' he or she is. "In the last analysis," Day says, "companies don't really know how profitable customers are."

Rolling the DiceCLV is an intuitively appealing concept, but one that for a variety of reasons can be very hard to implement, notes Wharton marketing professor David Bell in an article entitled, Seven Barriers to Customer Equity Management.

Collecting data on CLV can offer particular companies a number of benefits, Bell adds. For example, the individual transaction data collected by a hotel helps the company identify its best customers and cross-sell them other products. It also allows company marketers to target that group for customer feedback. Using that feedback, the company can then make smarter decisions about where to most efficiently allocate its marketing resources. Suppose the data shows that a significant percentage of the customers come from upstate New York and are in their 50s; the hotel can use that profile for more accurate outreach, he notes.

Bell points to Harrah's Casino as a CLV success story. Based on information gleaned from its loyalty program, Harrah's can now figure out "who is coming into the casino, where they are going once they are inside, how long they sit at different gambling tables and so forth. This allows them to optimize the range, and configuration, of their gambling games."

Others cite the health care and credit card industries, direct marketers and online email marketers as potential benefactors of CLV data, in part because they are characterized by direct customer contact and easy tracking abilities. For instance sales forces within the pharmaceutical industry, Dreze points out, can use relevant data to decide how often they should visit doctors' offices to pitch their companies' drugs.

Basically, says Day, CLV is most applicable "any time you have a database with customer profile and transaction information. But if you are working through channels - using a value-added retailer, for example, or any similar situation where you don't have a direct relationship with the customer - then it is not as easy to implement."

Beware Those Angry CustomersNow that marketers can collect better purchase transaction data to help determine a customer's lifetime value, how should this data be used?

The answer, suggest some researchers, is "cautiously."

One of the difficulties with implementing the CLV approach, adds Bell , is that the models forecasters use are very sensitive to assumptions. For example, models frequently make assumptions about how long a customer will continue a relationship with the company, whether that relationship is an active one and how much the customer will spend. Yet some of these assumptions may be inappropriate. "Just because I spent $100 last year doesn't mean I will spend $100 this year," says Bell . "Or if a customer is inactive, is it because he has temporarily stopped using the product or has switched to a competitor?"

"And yet a lot of companies are now using some measure of your lifetime value to determine how they should treat you," he adds. "If I am an average customer I get put on hold. Otherwise, two rings and I strike right through to a real person. But that assumes that people are fairly static. You have put them in certain buckets and they stay there. Yet perhaps if you had treated me better in the beginning, I would have become a better customer."

Day cites the case of a manufacturer of large scale components who learns he has an unprofitable account. "What do you do? The account may be unprofitable but in these kinds of business markets, that account could be 15% of your sales. It takes a lot to announce that you can't afford to service them anymore ... Lifetime value is after the fact. The tricky part is forecasting the prospective value; how do you know what this customer will do in the future?" A company's biggest risk, he adds, is that they "inadvertently turn off customers" who may have become profitable to them in the long term.

Fader suggests that some CLV models ignore the "inherent randomness" of individuals. "These models look at customers' past behavior and view each one as if he or she were a fixed annuity that pays off at certain stages ... But the pattern of past transactions isn't the best, or the only, predictor of the future."

Water Skis and GogglesIn cross-selling, a company that has sold you water skis, for example, will try to also sell you goggles. For marketers, the appeal is clear. "It's easier to sell to somebody that you already know," says Dreze. "It is trying to maximize the value of the relationship that you already have." Fader, however, is "somewhat skeptical of the tactic. If someone's behavior within a category is largely random, then when you take the randomness in one category and cross it with the randomness in another category, it's often very hard to make any valid connections."

Up-selling can also be problematic. Consider Amazon, which provides free shipping once a customer spends "x" dollars, or offers a second book for a discounted price once the customer has bought the first book. "In the Amazon example, perhaps a customer would have paid full price for the second book and didn't need the reduced offer," says Fader. "Some companies put too much emphasis on up-selling. It's hard to quantify the true impact of these efforts. Looking at the sales numbers alone doesn't indicate the amount of incremental profitability that can be directly tied to the marketing effort."

A sales tactic similar to cross-selling is multi-channel marketing. "It used to be that most companies had only one touch point with the customer," says Fader, "but now there are many kinds of retail outlets, plus the Internet, direct mail, call centers, etc. It leads to an issue of resource allocation. If one customer uses the Internet and another uses the call center, should we treat them differently? Clearly you might want to push some people to the Internet because it's cheaper than staffing a call center, but the question is, which customers? What are the behavioral characteristics of people who can be pushed? Should you risk angering loyal call center store customers by trying to move them online or should you focus on less loyal ones even if you can't get as much value out of them?"

What it gets down to, says Fader, is that "some selling tactics are good, some are bad, but in general it's hard to sort out the returns on these marketing investments and link them back to ongoing CLV measurement/management. As companies try out many different tactics on their customers, they inadvertently 'contaminate' the CLV numbers, making it even harder to figure out which customers to target or ignore in the future."

Ongoing ResearchIn a recent paper entitled, , Fader, along with co-authors Bruce Hardie, Chun-Yao Huang and Ka Lok Lee, look at how database marketers assessed the value of different customer groups in relation to their past behavior patterns Investigating Recency and Frequency Effects in Customer Base before CLV became so widely-used among managers. "The most popular framework classified prospects based on RFM: the recency, frequency and monetary value of past transactions," Fader says.

RFM has its roots in direct marketing, one of the most progressive industries in terms of using CLV concepts. Fader and his colleagues wanted to know how the simple RFM measures relate to the more complex CLV estimates, perhaps as "leading indicators" of future purchasing. "If you have a customer who has bought a lot of merchandise but not lately, and a customer who has bought some merchandise lately, which one is better in terms of CLV and is therefore more desirable?" Fader asks, referring back to the opening example. "And how do the tradeoffs between recency and frequency play into this?"

In their paper Fader and his colleagues suggest that simple statistics such as recency and frequency can in fact offer valid estimates of future lifetime values, i.e. "that a limited amount of summarized transaction data, when viewed the right way, can yield CLV forecasts that are just as accurate as those generated from the entire highly-detailed purchase history. The challenge for practitioners is knowing which summary statistics to use, and how to use them correctly. Many common 'rules of thumb' don't lead to very effective managerial policies," he says.

In Biases in Managerial Inferences about Customer Value from Purchase Histories: Intuitive Solutions to the Mailing-List Problem, Fader, David Schweidel and Robert J. Meyer set aside their complex equations in an effort to gain a better understanding of these rules of thumb. Fader recognizes the fact that "in most real world settings, the identification of key customers still has a strong intuitive component." In other words, despite modeling tools that use purchase transaction data to project future buying patterns, "managers make extensive use of subjective rules for identifying those customers who are likely to be the best (or worst) source of future sales."

The paper notes that little empirical work has been done examining the ability of managers "to form inferences about customer potential from sales histories..." The researchers address this issue by setting up situations where participants are shown purchase histories for a series of customers and asked to make different assessments about them.

What we found, says Fader, is that managers are inconsistent in their use of summary information such as recency, frequency and monetary value. The ways that managers use these cues vary drastically based on the task they are facing (e.g. figuring out which customers to add to the mailing list and which to drop) as well as the format used in presenting the customer purchase history data to managers. "It is vitally important to understand how managers are affected by these external factors before we encourage them to use any 'black box' models ... We need to balance our high-tech model-building efforts with a better understanding of the psychological aspects that underlie managerial decision making."

In A Renewable-Resource Approach to Database Valuation, researchersDreze and Andre Bonfrer offer a "new way to look at customers. Traditional CLV looks at the net present value of all income generated by one customer. Part of the assumption when marketers compute lifetime value is that at some point the customer will defect," says Dreze.

But when you make that assumption, he adds, "you severely underestimate the value of the database. If you were trying to optimize your marketing actions based on that formula, you would make the wrong decisions. The reason is because yes, you lose some percentage of your people every year, but you will acquire new ones. You need to take into account the acquisition of new customers when you value the database." In other words, Dreze says, "it is important to maximize the database value and not the customer value."

In other research, Noah Gans, Wharton professor of operations and information management, looks at the issue of CLV from an optimization standpoint: If a company has limited resources, which customers should it focus on?

Gans has developed theoretical models looking at how the average time that a customer stays with a service provider is affected by the overall level of service quality. "There can be a strong increase in the expected time a customer will stay with you as you improve the average service quality," he says. But there are other issues that also must be considered: What is your competitor doing? What does it cost for a customer to switch services? How does the evolution of technology affect the transaction?

At some point a company makes inferences about what kind of customer it is dealing with. "Then it takes an action offering the customer a certain level of service quality. In a call center, for example, this would mean giving the customer priority over other callers. That is an operating control the company is using to manage what the customer gets and the costs of serving that customer."

Gans says he want to use marketing models to make better operating decisions. "I am waiting for somebody to hand me a model of how customers behave - how they respond to different levels of services - and then I can describe the costs of providing a certain quality of service."

He uses the example of cross-selling. "It's a very simple problem. You decide at the end of a service whether you should cross-sell. At a call center, for example, cross-selling from an operations point of view adds length to the time of a call and makes other callers wait longer. You need to know how much cross-selling you want to do, when to do it, how much extra capacity it takes, and so forth.

"Any decisions have to take into account the four core marketing factors: price, promotion, product and place of distribution, which all involve marketing but which also have a direct impact on operations."

Gans addressed some of these issues in a recent paper entitled, Customer Loyalty and Supplier Quality Competition. The paper, he says, comes up with mathematical formulas for a service provider's "share of customer" as a function of its and its competitors' overall levels of service.

In terms of maximizing CLV, Gans believes that for companies there is value to tracking the history of what each customer does and deciding, based on that history, what bucket to place the customer in. "Then, based on your inference about the characteristics of that bucket, you can decide how best to treat these customers, whether it's cross-selling, up-selling or whatever. But you have to temper that decision because at any given time a customer comes to visit you, you don't really know what kind of customer he or she is. So your optimal decision has to take into account your uncertainty about how the customer will respond."

Published: December 07, 2011 in Knowledge@Wharton

Amazon.com will lose money on each $199 Kindle Fire it sells, but hopes to make back that money and more on tablet users who are expected to spend more than other customers. Sprint is not expected to turn a profit selling Apple's iPhone for at least three years, but expects that gamble to pay off in happier users who will bring in more subscribers.

The principle underlying these moves is customer lifetime value (CLV), a marketing formula based on the idea of spending money up front, and sacrificing initial profits, to gain customers whose loyalty and increased business will reap rewards over the long term. It is a model that is becoming more and more popular among technology companies, including Amazon, Sprint, Netflix and Verizon. And as software companies increasingly turn to subscription-based business models through cloud computing, CLV will become an even larger issue, according to Wharton experts.

The CLV formula looks at the cash flows that are tied to building a relationship with consumers. Companies compute the value of their first interaction with a customer and forecast how much that user is worth in future revenue, both from the purchases he or she will make and from recommending the firm to others, who then sign on as new customers. Firms typically expect to recoup their initial investment within three to seven years -- not exactly a lifetime, but a notable period in a business environment where many firms are under intense pressure from shareholders to make investments that lead them to exceed earnings expectations quarter after quarter.

"CLV can apply in any setting, but applies best in a contractual arrangement," Wharton marketing professor Peter Fader says. Most customers who buy an iPhone from Sprint will agree to a multi-year service contract with the carrier. Amazon offers a monthly subscription for its Prime service that provides free shipping and additional perks to Kindle users, "but there are different metrics for every business," Fader notes. "The first step is to tailor the lifetime value calculation to the business setting at hand."

Wharton marketing professor Jehoshua Eliashberg describes CLV as a spin on the model used by consumer goods companies that sell higher-end razors -- the firms take a loss on the initial investment, but make the money back over time through purchases of razor blades. Kodak used to sell cameras at a loss and make money from film sales, Eliashberg points out. "The CLV concept has been around, but few companies have had the technology to track the customer, know the usage on an individual basis and quantify behavior."

Yet technology companies that deliver services over digital networks and websites have the ability to collect data about how and where consumers are using their services. For example, Amazon provides product recommendations based on a user's purchase history and that of those with similar habits. On Amazon's most recent earnings conference call, chief financial officer Tom Szkutak noted that, since launching the Kindle e-reader, the company has observed that those who own the device also purchase more content, such as e-books or web applications, from the company.

But Wharton experts warn that CLV is not always a winning proposition. Firms may find it difficult to collect and aggregate the data they need to make accurate predictions, and their assumptions about consumer habits from that information could easily turn out to be wrong. "We're at this weird 'Y' in the road where companies are going in different directions. There are no standards on how CLV is calculated and what needs to be reported," Fader says. "We need better standards to make CLV more uniform and give it legitimacy."

Nevertheless, Fader predicts that the concept behind CLV is likely to become more popular in the technology industry. "Even if companies aren't doing the math the right way, customer acquisition is an investment that can pay off in the long run," he says.

Old Idea, New SpinThe basic concept of loss leaders "is as old as retail," notes Kevin Werbach, a Wharton professor of legal studies and business ethics. "And it's a big part of the business model for many Internet-based services that offer functions cheaply or for free in order to monetize at the back end. Google loses money at first on search engine users, and Zynga loses money on players of its games, but both turn tidy profits [through] their huge user bases. That doesn't mean the approach always works."

Indeed, Werbach adds that the entire concept of CLV assumes that a company can keep a customer long enough to generate a profit. But many of the assumptions that are included in a CLV model are out of a firm's control. For example, users may purchase an iPhone from Sprint, but switch to Verizon or AT&T after their initial two-year contracts expire -- taking with them some of the money that went into the firm's calculation of CLV.

Fader notes that Verizon sacrificed earnings in 2005, 2006 and 2007 to build out FiOS, the company's speedy, fiber-optic-based broadband Internet and cable TV service. Initially, it cost Verizon $1,400 a household to install FiOS; by October 2006, the company reported that its costs were down to $845 for each home. The firm was willing to incur those upfront costs based on the assumption that customers would not switch to a cable rival before Verizon recouped its upfront payment. The model seems to have worked for Verizon; FiOS now accounts for about 60% of the firm's wired consumer revenue.

According to Fader, following a CLV model can keep companies from panicking when making big strategic decisions. For instance, Netflix recently decided to raise subscription prices as the company's business focus shifts from offering DVDs by mail to a model based on Internet streaming. The price hikes and a plan (which was ultimately aborted) to split its DVD and streaming services into two separate companies outraged customers and caused a significant number to cancel their subscriptions, causing Netflix to project losses for 2012. Focusing on streaming lowers the company's overhead because it doesn't have to pay postage and handling for sending DVDs through the mail. In 2010, Netflix spent $18.21 to acquire a customer, meaning it would take nearly 3 months to turn a profit on a subscriber paying $7.99 a month. In 2009, Netflix spent $25.48 to acquire each customer. For the third quarter of this year, Netflix spent $15.25.

"Netflix's screwups are a blip," Fader states. "Lifetime value is the future and keeps us from overreacting. In this particular case, Netflix screwed up with the communication [of the service changes]. The way it split the business and prices was smart. The way it announced the changes was ridiculous. Dropped subscriptions are likely to be picked up again because Netflix really doesn't have a comparable competitor."

According to Fader, companies should make several bets based on CLV and assume that some will fail. "Some companies will see their first disaster and give up. You need to take the good with the bad."

The Pay OffSprint and Amazon provide interesting case studies on the effectiveness of CLV, note Wharton experts, who were more optimistic about Amazon recouping its initial investment to bring customers into the fold with the Kindle Fire than Sprint's gamble on the iPhone.

The wireless carrier has guaranteed Apple a minimum of $15.5 billion over four years as part of the deal to sell the iPhone, meaning that Sprint will not make money on the partnership until at least 2015. On October 26, Sprint CEO Dan Hesse likened the iPhone to acquiring a star major league baseball player. "We expect that customer lifetime value for the iPhone customer will be at least 50% greater than a typical smartphone user, driven primarily by more efficient use of our network and lower churn," Hesse noted. "In addition, [there is] the upside of more, new revenue [from] new fans to offset the fixed cost of our stadium, if you will, because we expect the iPhone to generate a significantly higher number of new users to Sprint."

But Eliashberg suggests that Sprint's thinking may be faulty. "Sprint has to consider how competitive stress [from Verizon and AT&T, which also offer the iPhone] will affect lifetime value," Eliashberg says. "If AT&T drops its iPhone price at some point, Sprint will have to match that price. That move would extend the payback period." To Eliashberg, Sprint's move to get the iPhone on its network is more about staying in the wireless race than lifetime value of a customer.

Fader, however, argues that Sprint's plan does fit the CLV profile. "Sprint's business is contractual, and it has the tools to track each customer and collect granular data. All the ingredients are there." Wharton marketing professor Eric Bradlow says Sprint's plan for the iPhone is a classic example of trying to capitalize on CLV, but he predicts that Amazon is more likely to be successful with its efforts related to the Kindle Fire. "Amazon has the more direct distribution model and hence more direct control over CLV," Bradlow notes.

Werbach agrees. "As the manufacturer of the Kindle Fire, Amazon can influence the costs, the interim losses and the ultimate gains by virtue of its own business decisions," he says. "Amazon also will benefit from declining manufacturing costs over time and with volume. It doesn't help Sprint if Apple comes up with a cheaper bill of materials for the iPhone."

Amazon's approach to CLV includes subscriptions as well as additional sales, Bradlow notes. If a Kindle Fire subscriber becomes a member of Amazon Prime, the company's free shipping and movie streaming service, the e-commerce giant lands $79 a year in additional revenue. The customer may then buy more physical goods due to free shipping, as well as apps, videos and e-books, helping Amazon to easily offset the initial loss on the tablet, Bradlow adds.

Research firm IHS iSuppli estimates that the cost of the materials to produce Amazon's Kindle Fire is $201.70. Other analysts indicate that Amazon is losing money on every Kindle Fire sold, but disagree on the exact hit to its bottom line. "A new purchaser of the Kindle Fire is worth more to Amazon than the profit made on the initial hardware," says Wharton operations and information management professor Karl Ulrich. "That purchase may represent a lost sale of Barnes & Noble's Nook, and incrementally more sales of books from the Kindle store."

Published: March 01, 2006 in Knowledge@Wharton

That Wal-Mart, the low-cost mass retailer, and BMW Group, a high-end automaker, can have anything in common seems improbable. But they do. Both companies have figured out a way to put a long-term value on their customers, and are able to more effectively direct their marketing investment than most companies, says Wharton marketing professor David Reibstein.

While the German automaker has calculated the value of its customers through a general formula, and as a result is in a position to direct a significant amount of investment to acquire a new customer, Walmart.com, the online division of Wal-Mart, has leveraged its consumer tracking tools to work out even more precisely what the value of each of its customers is.

"They (Walmart.com) know when they put Valentine's Day flowers on sale how much it costs to send that message, what percentage of customers end up on that site because of that message, how much money they will spend, and what is the likelihood of that customer coming back and buying other things," says Reibstein. They don't simply look at one-time purchases, but at all the purchases afterwards, and use that information to calculate the value of spending advertising dollars. "They have that down to a science for almost all of their advertising."

But companies like BMW and Wal-Mart are few and far between. Most companies routinely neglect the long-term value of marketing investment and thus do not acknowledge the lasting value of acquiring a customer. Instead, they adopt a "here and now" policy with regard to marketing dollars, says Reibstein.

Looking at the Long TermA central message that Reibstein wants to convey to both finance and marketing executives is that it is a huge mistake to treat marketing investments as short term. He advises finance executives not to hold marketing accountable for what happens in year one, but instead view marketing costs as a longer term investment that has an impact over time. "There is a lot to gain in trying to measure and capture what the long-term value is," he says. "And that is where I think the failure has been. We have not done a good job of capturing that."

General accounting rules require marketing investments to be treated as a short-term expense, which is the primary reason that most companies focus narrowly on the short-term revenue generated by marketing dollars. "Almost all other investments that a firm makes are treated like [long-term] investments," says Reibstein. For example, when a company builds a plant it is depreciated over time, and if it has investments in research and development they are amortized over the useful life. "If you looked at either one of those types of investments and tried to evaluate the value of doing them, you would always come up with a negative return."

Reibstein says few companies make use of the tools available to measure the long-term value of a customer, and there is not enough understanding and interaction between finance and marketing departments to develop this concept. "I think a perspective and philosophical change is absolutely essential for companies" if they want to make the most efficient use of marketing investments, he adds.

Measuring IntangiblesAn important step in that direction is quantifying the value of a firm's key intangible assets, which are mostly marketing-related such as brands, customer base and customer loyalty.

A common metric that companies can use to assess the long-term value of customer acquisition costs is lifetime value, which is the present value of all future profits generated by a customer. While a simple formula involving customer retention rate, acquisition costs, profit margin and discount rate will produce that value, it is the concept of a lifetime value that needs to be recognized, says Reibstein. Even a small percentage of increase in retention rates can raise profits considerably, depending on the other variables.

Reibstein points to PepsiCo, the soft drink maker, as another company that has recently assessed the long-term value of its customers. The company concluded that its number-one drink is Diet Pepsi rather than regular Pepsi, and that is where it is directing its marketing dollars, he says. "If you do some of the analysis, you will find that diet drinkers are much more loyal than non-diet drinkers, and that leads you down the path of putting greater emphasis on [the former] because loyal customers translate into long-term sales, which translates into a longer term customer value."

Another important intangible that companies tend to ignore is branding, says Reibstein. "Most companies do not go out and measure their brand's long-term value." Advertising dollars may not lead to immediate sales, but they may shift some consumer attitudes that could subsequently lead to sales, increase the lifetime value of an existing customer, or lead a customer to pay more for a brand.

There are a variety of ways to measure a brand's value, and one way is through conjoint analysis, a statistical tool which can help to determine the incremental price companies can charge for a product as a result of their brand and the added market share that companies can capture through their brand, says Reibstein. In marketing parlance, conjoint analysis focuses on the joint effects of multiple product attributes on product choice. It involves providing a sample of customers with choices that are systematically varied on a set of attributes. The customers' preferences or likelihood of buying reflect the weight they place on each attribute in order to make a choice. These weights are typically calculated using regression analysis.

Such analysis and concrete measurement of intangible asset values will not only help put marketing investment in perspective for CEOs and CFOs; it can also be used as a tool in customer relationship management, Reibstein notes. He points in particular to NASCAR, which has mastered the art of demonstrating to their sponsors the value of their sponsorships. NASCAR provides a comparison between the cost of brand name exposure that a sponsor gets and the cost of getting the same level of exposure through traditional media. It also provides information on purchasing probabilities of sponsors' products, as well as change in sales before and after sponsorships.

Working out the multi-year impact of intangible assets is not a call for increasing marketing budgets, adds Reibstein, but rather a way to bring out the true value of marketing expenditure. "The problem is not that investment in marketing is ineffective or has a poor rate of return," says Reibstein. "It is much more an issue of making sure that companies can capture the long-term value of marketing."

Have you ever watched as one of your competitors raked in profits from customers that you had decided not to bother acquiring? Perhaps this happened because your company based its decision on the traditional method of calculating customer lifetime value (CLV). That could be a costly mistake.

The standard CLV approach calculates the net present value (NPV) of all anticipated cash flows coming in (revenues) and going out (marketing dollars spent) over some time span (months, years, or even decades) for a given customer. Keep customers who show a positive NPV for the marketing investment, the rules say, and drop the ones who don't. Those are rational choices at the time of the calculation-but only then. The conventional calculation is thus rather static and actually flawed, because you are not able to factor in a company's flexibility to cut a given customer loose at any time. Flexibility means options, and options have value.

In analyzing the seller's option to abandon unprofitable customers, my colleagues and I looked at 12 years of purchasing data for more than 100,000 customers of a specialty catalog company. What we found was astonishing: The difference in CLV using the real-options approach versus the traditional approach was, in some cases, as much as 20%. More important, some negative CLVs actually turned positive when the value of the real options was considered. In other words, we found that neglecting a customer with a negative NPV-as traditionally calculated-may be exactly the wrong choice: He could turn out to be highly profitable.

Companies have been using real options for a long time to optimize their investment portfolios. It's time they applied them in the valuation and management of their investment in customers, too. Here's a five-step process for bringing real-options analysis into the NPV calculation:

1. Estimate the future purchasing behavior (that is, the probability of purchase and dollar amount expected to be spent) for a set of customers, using the common RFM (recency, frequency, and monetary value) approach. This determines expected revenues.

2. Calculate costs generated per customer per period.

3. Use those two inputs to estimate the profit contribution for each customer over the time horizon under consideration, for example ten periods.

4. For each period, determine whether the expected future profit contribution for that customer might be negative.