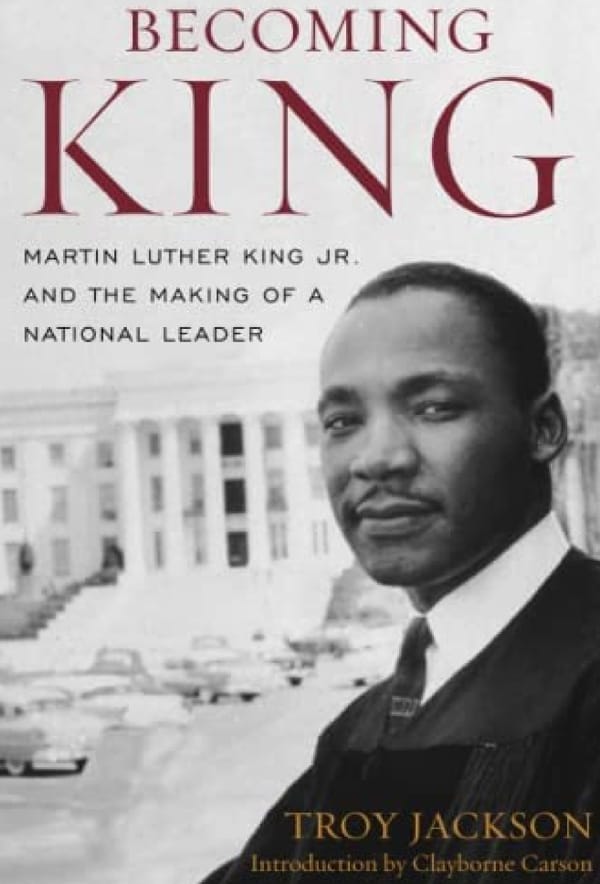

Becoming King: Martin Luther King Jr.

Becoming K ing

Civil Rights and the stRuggle foR BlaCk equality in the twentieth CentuRy seRies editoRs Steven F. Lawson, Rutgers University Cynthia Griggs Fleming, University of Tennessee advisoRy BoaRd Anthony Badger, Sidney Sussex College S. Jonathan Bass, Samford University Clayborne Carson, Stanford University Dan T. Carter, University of South Carolina William Chafe, Duke University John D’Emilio, University of Illinois, Chicago Jack E. Davis, University of Florida Dennis Dickerson, Vanderbilt University John Dittmer, DePauw University Adam Fairclough, University of East Anglia Catherine Fosl, University of Louisville Ray Gavins, Duke University Paula J. Giddings, Smith College Wanda Hendricks, University of South Carolina Darlene Clark Hine, Michigan State University Chana Kai Lee, University of Georgia Kathryn Nasstrom, University of San Francisco Charles Payne, Duke University Merline Pitre, Texas Southern University Robert Pratt, University of Georgia John Salmond, La Trobe University Cleve Sellers, University of South Carolina Harvard Sitkoff, University of New Hampshire J. Mills Thornton, University of Michigan Timothy Tyson, University of Wisconsin–Madison Brian Ward, University of Florida

Becoming K ing Martin Luther K ing Jr. and the Mak ing of a National Leader tRoy JaCk son intRoduCtion By ClayBoRne CaRson The UniversiTy Press of K enTUcKy

Copyright © 2008 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 12 11 10 09 08 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jackson, Troy, 1968– Becoming King : Martin Luther King, Jr. and the making of a national leader / Troy Jackson. p. cm. — (Civil rights and the struggle for Black equality in the twentieth century) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8131-2520-6 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. King, Martin Luther, Jr., 1929–1968. 2. African American civil rights workers—Biography. 3. Baptists—United States—Clergy—Biography. 4. African Americans—Civil rights—Alabama—Montgomery—History—20th century. 5. Montgomery (Ala.)—Race relations. 6. Segregation in transportation—Alabama— Montgomery—History—20th century. I. Title. E185.97.K5J343 2008 323.092—dc22 [B] 2008025041 This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials. Manufactured in the United States of America. Member of the Association of American University Presses

For Amanda, Jacob, Emma, and Ellie

Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction by Clayborne Carson xi Prologue 1 1. “The Stirring of the Water” 9 2. “The Gospel I Will Preach” 35 3. “Making a Contribution” 53 4. “They Are Willing to Walk” 85 5. “Living under the Tension” 115 6. “Bigger Than Montgomery” 147 Epilogue 181 Notes 187 Bibliography 229 Index 241

Acknowledgments This book reflects the valuable suggestions and recommendations of many scholars and readers. Dr. Gerald Smith’s knowledge of the field helped me clearly define the scope of the work. Dr. Smith also provided detailed feedback on the entire manuscript at several points during the writing process. Many other professors from the University of Kentucky provided helpful reflections and raised important questions that helped enhance this work, including Dr. Kathi Kern, Dr. Ronald Eller, Dr. Philip Harling, Dr. Eric Christiansen, and Dr. Armando J. Prats. Lexington Theological Seminary’s Dr. Jimmy L. Kirby also provided useful feedback. Other scholars also contributed to this work, including Dr. Clay- borne Carson, senior editor of the Martin Luther King Jr. Papers Project, who inspired me to take on a project that incorporated the work I had done as an editor with the King Papers Project. Dr. Carson and his wife, Susan Carson, also provided wonderful hospitality during research trips to Stanford University. Other editors with the project, including Dr. Ki- eran Taylor and Dr. Sue Englander, provided helpful suggestions. I am honored that the King scholar Dr. Keith Miller read the entire manu- script and offered helpful suggestions and encouragement. Theologian Dr. Curtis DeYoung of Bethel University also provided helpful feedback. Others who read and commented on the work include Brandie Atkins, Aaron Cowan, Rob Gioelli, Emily Gioelli, Les Stoneham, and Jeff Suess. Thanks to Susan Brady for her very diligent editorial work on this manu- script, and for her many helpful suggestions. I am thankful for the support of University Christian Church, where I serve as pastor. The congregation has encouraged my academic pursuits and provided a sabbatical that allowed me to complete the bulk of my research. My family has been supportive throughout. My wife, Amanda, has encouraged my educational pursuits throughout our marriage. This man- ix

x Acknowledgments uscript would not have been completed without Amanda’s patience and perseverance. My children, Jacob, Emma, and Ellie, helped me keep my priorities in order during the writing process. My parents, Robert and Mary Jackson, encouraged my academic pursuits from an early age. Thank you to my entire family for your love and support through the years.

Introduction What if Martin Luther King Jr. had never accepted the call to preach at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery? Would he have be- come a famed civil rights leader? Would the bus boycott movement have succeeded? How was the subsequent course of American history altered by the contingencies that brought together King and the Montgomery movement? Although it may be difficult for those who see King as a Great Man and national icon to imagine contemporary America without taking into account his historical impact, Troy Jackson allows us to understand the evolution of King’s leadership within a sustained protest movement ini- tiated by others. Rather than diminishing King’s historical significance, Jackson’s revealing, insightful account of the Montgomery bus boycott invites a deeper understanding of the many unexpected and profound ways that movement transformed King as well as other participants. Jack- son points out that King himself was aware of his limitations and the accidental nature of his sudden fame. Even as he rose to international prominence as spokesperson for the boycott, King often cautioned against the tendency of others to inflate his importance. “Help me, O God, to see that I’m just a symbol of a movement,” he pleaded in a sermon de- livered after the successful end of the boycott. “Help me to realize that I’m where I am because of the forces of history and because of the fifty thousand Negroes of Alabama who will never get their names in the pa- pers and in the headline. O God, help me to see that where I stand today, I stand because others helped me to stand there and because the forces of history projected me there. And this moment would have come in history even if M. L. King had never been born.” He added, “Because if I don’t 1 see that, I will become the biggest fool in America.” Troy Jackson was a colleague of mine in the long-term effort to pub- lish a definitive edition of The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., and his xi

xii Introduction Becoming King builds on vast documentation that the King Papers Project has assembled since 1985, when Coretta Scott King named me to direct the project. The hundreds of thousands of documents that the project’s staff examined in hundreds of archives and personal collections have illu- minated not only King’s life but also the lives of thousands of individuals who affected King’s life and were affected by him. The third volume of The 2 Papers focused on the Montgomery bus boycott, but Jackson also makes effective use of the original research he contributed to volume 6, Advocate 3 of the Social Gospel, September 1958–March 1963, which traces the develop- ment of King’s religious ideas. The latter volume brought together many of King’s student papers from Crozer Theological Seminary and Boston University with a treasure trove of materials from the files that King used to prepare the sermons he delivered at Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, and other places. These ser- monic materials, which remained in the basement of King’s Atlanta home for three decades after his death, provided a new window into the experi- ences that shaped King before his arrival in Montgomery. They also gave Jackson a sensitive understanding of how King’s experiences during the boycott reshaped his identity as a social gospel minister. Jackson’s years of immersion in King’s papers, his background as a clergyman, and his years of in-depth research regarding the Montgomery boycott movement allow readers of Becoming King to comprehend the complexity and imaginative possibilities of religious biography converging with social history. Although Jackson’s study provides ample evidence to support the conviction of many of Montgomery’s black residents that their move- ment “made” King into the leader capable of all he would later accom- plish, the interaction of the man and the movement was by no means one-sided. King arrived in Montgomery with a wealth of experiences and intellectual exposure that served him well once Rosa Parks suddenly changed the course of his life. After Parks’s arrest on December 1, 1955, for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white man, King was at first reluc- tant to assume a leading role in the boycott movement, having rejected previous entreaties to seek the presidency of the local NAACP branch. Yet Jackson shows that he was singularly well prepared to offer a kind of leadership that helped transform a local movement with limited goals— such as more polite enforcement of segregation rules—into a movement

Introduction xiii with far-reaching implications for race relations in the United States and throughout the world. The Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) had numerous other leaders capable of mobilizing and sustaining a mass movement, and King was not being overly modest in asserting that the boycott would have happened even if he had never lived. But King’s presence made a major difference in determining how the boycott would be seen by those who supported or opposed it and by those who would later contemplate its significance. Although King was surprised when other black leaders chose him as MIA spokesperson, his hastily drafted remarks at the MIA’s first mass meeting on December 5, 1955, were a remarkable example of his abil- ity to convey the historical significance of events as they unfolded. Like his great speech at the 1963 March on Washington, King’s speech at Montgomery’s Holt Street Baptist Church was a compelling religious and political rationale for nonviolent resistance in pursuit of ultimate ra- cial reconciliation. At a time when the one-day boycott had received little attention outside Montgomery and when few could have been certain that it could be continued for days or weeks (much less for 381 days!), King audaciously linked the boycott’s modest initial goals to transcendent principles: “If we are wrong, the Supreme Court of this nation is wrong. If we are wrong, the Constitution of the United States is wrong. If we are wrong, God Almighty is wrong. If we are wrong, Jesus of Nazareth was merely a utopian dreamer that never came down to earth. If we are wrong, justice is a lie, love has no meaning. And we are determined here in Montgomery to work and fight until justice runs down like water and righteousness like a mighty stream.” While King assumed the crucial task of inspiring black residents, oth- er MIA leaders were already beginning to establish the transportation alternatives that sustained the boycott. As Jackson points out, resourceful and experienced NAACP leaders such as Parks and E. D. Nixon had chal- lenged the southern Jim Crow system years before King’s arrival. Simi- larly, Jo Ann Robinson of Montgomery’s Women’s Political Council did not require King’s guidance before drafting and duplicating thousands of leaflets urging residents to stay off buses. These individuals, along with others such as Ralph Abernathy, might well have gained more promi- nence if they had not been overshadowed by King. Still, although the

xiv Introduction boycott had already attracted overwhelming black support when he be- came head of the MIA, King’s uplifting oratory on the first night of the boycott provided an unexpected stimulus to a mass movement already in progress. Using imagery that subtly linked the boycott to the struggle to end slavery, King’s address concluded with a portentous passage that be- came an accurate prediction of the nascent movement’s place in the long struggle for social justice: “Right here in Montgomery, when the history books are written in the future, somebody will have to say, ‘There lived a race of people, a black people, fleecy locks and black complexion, people who had the moral courage to stand up for their rights. And thereby they injected a new meaning into the veins of history and of civilization.’” King was neither a historian nor a civil rights lawyer, but his training and experiences as a Baptist minister gave him an inclusive, historical per- spective that allowed him to understand the civil rights militancy spurred by the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education as confirma- tion of his prophetic worldview. Although Jackson recognizes that King would sometimes find it difficult to translate his intellectual radicalism into civil disobedience, his sympathy for the oppressed was deeply root- ed and enduring. One of King’s earliest seminary papers, written when he was nineteen—seven years before the start of the Montgomery boy- cott—demonstrates that he was already committed to a ministry based on knowing “the problems of the people that I am pastoring.” At this early stage of King’s ministry, moreover, civil rights reform was only an aspect of his social gospel agenda. When King defined his pastoral mission—“I must be concerned about unemployment, slumms [sic], and economic insecurity”—racial segregation and discrimination were conspicuously absent from the list, which was a prescient suggestion of his antipov- 4 Although he was undoubtedly concerned erty crusade two decades later. about civil rights, his basic identity as a social gospel minister was already firmly established before the Brown era of mass civil rights activism. Growing up as the son of the Reverend Martin Luther King Sr., the younger King had absorbed the essentials of the social gospel at an early age. Daddy King was part of a well-established tradition of black minis- ters, particularly those in black-controlled churches, also providing po- litical as well as spiritual leadership. As the younger King became aware of the dangers his father faced while advocating black voting rights and

Introduction xv equal salaries for black schoolteachers, he came to admire his father’s ability to stand up to whites—“they never attacked him physically, a fact that filled my brother and sister and me with wonder as we grew up in this tension-packed atmosphere.” Such formative experiences as well as his own encounters with southern racism infused the younger King with an abhorrence of segregation, which he found “rationally inexplicable 5 Although as a teenager King would reject and morally unjustifiable.” his father’s biblical literalism, he would retain his admiration for a father who “set forth a noble example I didn’t mind following” and whose “moral and ethical ideals” remained precious to him “even in moments of theological doubt.”6 When King accepted his call to Dexter, he cited the same social gospel credo (Luke 4:18–19) that his father had used in 1940 while advising fellow ministers regarding “the true mission of the church”: “The spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me to preach the Gospel to the poor; he hath sent me to heal the broken- hearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, and the recovering of sight 7 King’s conception to the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised.” of his social gospel mission would evolve during his years at Crozer, due in part to the considerable impact of Reinhold Niebuhr’s neo-orthodox critique of liberal Christianity. He continued to seek a middle ground between Walter Rauschenbusch’s social gospel optimism and Niebuhr’s skepticism about human perfectibility by eclectically synthesizing “the best in liberal theology with the best in neo-orthodox theology.”8 King’s underlying commitment to his social gospel ministry did not waver. In- deed, it may have been the unyielding nature of King’s basic theological convictions that limited his prospects as a theologian. A scholarly synthe- sizer rather than an original scholar, he drew upon the ideas of more cre- ative theologians—sometimes without attribution, and without adding many new insights of his own. He graduated from Crozer highly adept at explaining and defending his basic religious beliefs. Modern notions of historical exegesis assuaged the religious doubts of his teenage years and answered his need for religion that was “intellectually respectable as well as emotionally satisfying.”9 Similarly, his graduate studies in systematic theology at Boston University provided opportunities to incorporate the personalist theology of his mentors into his belief system. King’s disserta- tion predictably rejected the views of theologians Paul Tillich and Henry

xvi Introduction Nelson Wieman, who, in King’s view, reduced God to an abstraction. “In God there is feeling and will, responsive to the deepest yearnings of the hu- 10 man heart; this God both evokes and answers prayers,” King concluded. Although King’s academic writings would provide a scholarly gloss for his oratory in Montgomery, it was in King’s personal correspondence and his early sermons that he first expressed forcefully the social gospel vision that distinguished his leadership during the bus boycott and afterward. In particular, King’s correspondence with Coretta Scott during their court- ship in Boston reveals that he expected a major social transformation ex- tending beyond civil rights reform. Because King was attracted to Scott partly because of her political involvement—she had been a Progressive Party activist during the 1948 election and involved in pacifist causes at Antioch College—he was able to confide to her his own radical leanings. “I imagine you already know that I am much more socialistic in my eco- nomic theory than capitalistic,” he wrote in a July 1952 letter prompted by Scott’s gift of Edward Bellamy’s socialistic fantasy Looking Backward 2000–1887 (originally published in 1888). King asserted confidently that capitalism had “outlived its usefulness,” having “brought about a system that takes necessities from the masses to give luxuries to the classes.” King added that the change “would be evolutionary rather than revolutionary. This, it seems to me, is the most sane and ethical way for social change to take place.” Although the public expression of such thoughts would have been political heresy, King informed his future wife that both capitalism and communism were inconsistent with true Christian values. Even Bel- lamy was faulted for failing “to see that man is a sinner . . . and will still be a sinner until he submits to his life to the Grace of God. Ultimately our problem is [a?] theological one.” Cautioning Scott against excessive optimism, King observed: “It is probably true that capitalism is on its death bed, but social systems have a way of developing a long and power- ful death bed breathing capacity. Remember it took feudalism more than 500 years to pass out from its death bed. Capitalism will be in America quite a few more years my dear.” King was not quite so candid in his sermons as in his letters to Scott, but the sermons he delivered while assisting his father at Ebenezer dur- ing the summer of 1953 (soon after his marriage in June) viewed racial segregation and discrimination in the context of a wide-ranging critique

Introduction xvii of the modern world and as aspects of a global struggle for peace with social justice. Several of these sermons focused criticism on modernity’s “false Gods”—science, nationalism, and materialism. Sharply criticizing American chauvinism and anticommunism, King offered blunt advice: “One cannot worship this false god of nationalism and the God of Chris- 11 In another sermon King prepared that sum- tianity at the same time.” mer, he insisted international peace was the “cry that is ringing in the ears of the peoples of the world,” but such peace could be achieved only when Christians “place righteousness first. So long as we place our selfish economic gains first we will never have peace. So long as the nations of the world are contesting to see which can be the most [imperialistic] we will [never] have peace. Indeed the deep rumbling of discontent in our world today on the part of the masses is [actually] a revolt against imperi- alism, economic exploitation, and colonialism that has been perpetuated 12 by western civilization for all these many years.” King’s comprehensive Christian worldview was perhaps most evi- dent in the sermon “Communism’s Challenge to Christianity,” which he delivered in August 1953 and, in various forms, later in his life. While rejecting communism as secularistic and materialistic, King nonetheless insisted that communism was “Christianity’s most formidable competitor and only serious rival.” Marxian thought, King argued, should challenge Christians to express their own “passionate concern for social justice.” Returning to the passage in the book of Luke that his father had used thirteen years earlier, King argued, “The Christian ought always to be- gin with a bias in favor of a movement which protests against the unfair treatment of the poor, for surely Christianity is itself such a protest.” Karl Marx could hardly be blamed for calling religion an opiate of the masses, King lamented. “When religion becomes [so] involved in a future good ‘over yonder’ that it forgets the present evils ‘over here’ it is a dry as dust 13 religion and needs to be condemned.” Less than a year after King delivered his sermon on communism, he accepted the call to become the pastor of the Dexter congregation and began to refine his unique leadership style. Jackson assesses the strengths and the limitations of this leadership, noting, for example, that King’s global prophetic vision ensured his prominence but sometimes obscured the pressing, prosaic concerns of the working-class MIA members who

xviii Introduction had regularly ridden buses and thus sacrificed the most on a daily basis during the boycott. Vernon Johns, King’s sometimes abrasive predeces- sor at Dexter, actually focused his ministry more than did King on the economic issues that were central to Christian social gospel. King, for his part, pushed gently yet consistently against complacency after becoming pastor of a congregation known to be difficult to control. Wary of the power of the church’s deacons, King used his acceptance address as an occasion to assert his spiritual authority and to suggest the immensity of the task ahead. Only twenty-five, he challenged his mostly older congre- gation to expand their vision: “It is a significant fact that I come to the pastorate of Dexter at the most crucial hour of our world’s history; at a time when the flame of war might arise at any time to redden the skies of our dark and dreary world; at a time when men know all [too] well that without the proper guidance the whole of civilization can be plunged across the abyss of destruction. . . . Dexter, like all other churches, must somehow lead men and women of a decadent generation to the high mountain of peace and salvation.” That some Dexter members welcomed King’s ambitious agenda would become evident during the bus boycott, but it is nonetheless worth noting that King not only encouraged church members to become reg- istered voters and NAACP leaders but also to see the southern Jim Crow system as part of a passing global order of colonialism and imperialism. In the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s Brown decision of May 1954, King became even more convinced that segregation was doomed, unless, as he warned in an address the following year to Montgomery’s NAACP branch, black Americans became “victims to the cult of inevitable prog- ress.” King also warned against becoming “so complacent that we forget the struggles of other minorities. We must unite with oppressed minori- ties throughout the world.”14 As Rosa Parks listened to King’s address, she might well have been encouraged to take her own stand against com- placency less than six months later. King’s words undoubtedly inspired black leaders who shared his sense that the southern Jim Crow system was a vulnerable anachronism. Soon after King spoke, he was invited to join the branch’s executive committee. Thus, the decision to elect King to head the MIA was unexpected, but the qualities of mind that King demonstrated in his early ministry

Introduction xix were well suited to the role of being the principal spokesperson of the boycott movement. His subsequent decade of civil rights leadership was, in some respects, a departure from his original social gospel mission, but only to the extent that he necessarily narrowed his focus to the southern issues of segregation and racial barriers to voting. Seen from the per- spective of his entire ministry, the years from Montgomery to the sign- ing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were a time during which he felt compelled to play down the radicalism of his social gospel Christianity. To be sure, during his entire public life, he would often describe the African American freedom struggle in the context of African and Asian anticolonial struggles, and he would often draw attention to the issue of international peace. But only toward the end of this decade of civil rights reform did these broader concerns become a central part of his message, as it was in his rarely heard Nobel lecture following his acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize in December 1964. Only after the Voting Rights bill had been enacted did King make clear that even this landmark reform did not fulfill his dream. Only then would he return to his social gospel mis- sion of achieving economic justice, bringing his ministry to Chicago and then Memphis as part of the Poor People’s Campaign. Only then, to the consternation of those who saw him merely as a civil rights leader, would he speak out unambiguously against war, imperialism, and militarism. It is worthwhile to speculate regarding what would have happened to King if he had not accepted the call to Dexter or if he had not been se- lected to head the MIA. If not for Rosa Parks, he might not have become the preeminent African American of his era or a Nobel laureate or have his birth commemorated with a national holiday. It is also likely that, if not for King’s role in the Montgomery bus boycott, the contributions of grassroots activists in Montgomery and other protest centers would be remembered differently. Jackson suggests, moreover, that King’s oratori- cal brilliance may have fostered his rise to international prominence while also diminishing his ability to sustain a mass movement. Not until the Bir- mingham campaign of 1963 would King experience a similar degree of success in mobilizing an entire black community. By acknowledging that the bus boycott had only a limited impact on the lives of Montgomery’s black working class, Becoming King is a necessary corrective to roman- ticized versions of civil rights progress and Great Man historical myths.

xx Introduction Yet Jackson also reminds us that historic social movements provide op- portunities for some men and women of all classes and backgrounds to rise unexpectedly to greatness. Having acknowledged the importance of contingency in King’s emergence as a leader, he demonstrates that King’s prophetic vision en- couraged others to see their resistance to injustice as more historically significant than would otherwise have been the case. Because of King, the African American freedom struggle gained a historical significance it would otherwise have lacked. The Montgomery bus boycott would have happened without King, but King’s oratory helped to ensure that the boycott became one of those exceptional local movements for justice that would send ripples of inspiration to oppressed people elsewhere. Clayborne Carson Notes 1. King, “Conquering Self-Centeredness,” August 11, 1957. 2. Birth of a New Age, December 1955–December 1956, ed. Clayborne Carson, Stewart Burns, Susan Carson, Peter Holloran, and Dana L. H. Powell (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1997). 3. Ed. Clayborne Carson, Susan Carson, Susan Englander, Troy Jackson, and Gerald L. Smith (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2007). 4. King, “Preaching Ministry” [September 14–November 24, 1948], in Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., 6: 72. 5. Clayborne Carson, ed., The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. (New York: Warner Books, 1998), 5. 6. Ibid., 16. 7. Quote in introduction to Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., vol. 1, Called to Serve, January 1929–June 1951, ed. Clayborne Carson, Ralph E. Luker, and Penny A. Russell (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1992), 33–34. 8. King, “How Modern Christians Should Think of Man,” November 29, 1949–February 15, 1950, in Papers, 1: 274. 9. Carson, ed., Autobiography, 15. 10. King, “A Comparison of the Conceptions of God in the Thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman,” April 15, 1955, in Papers, 2: 512. 11. King, “The False God of Nationalism,” July 12, 1953, in Papers, 6: 132. 12. King, “First Things First,” August 2, 1953, in Papers, 6: 144–45. 13. King, “Communism’s Challenge to Christianity,” August 9, 1953, in Papers, 6: 148–49. 14. King, “The Peril of Superficial Optimism in the Area of Race Relations,” June 19, 1955, in Papers, 6: 215 .

Prologue The history books may write it Rev. King was born in Atlanta, and then came to Montgomery, but we feel that he was born in Mont- gomery in the struggle here, and now he is moving to Atlanta for bigger responsibilities. —Member of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, November 1959 Every year in elementary school classrooms throughout the United States, teachers share heroic stories that took place in Montgomery, Alabama, during the 1950s. Young children learn about the arrest of Rosa Parks, the boycott of Montgomery city buses, and the emergence of a young Baptist preacher named Martin Luther King Jr. One doesn’t have to be a historian to know the significant role the Montgomery movement played in the emergence of a broader civil rights struggle during the 1950s and 1960s. Although historians have written countless books covering the life and career of Martin Luther King, while others have contributed dozens of studies that cover aspects of the civil rights movement in Montgom- ery, a narrative recounting the important influence of this community on 1 King’s career and civil rights leadership has yet to be written. Brave white and black activists of Montgomery had a significant im- pact on King’s leadership. Not only did a handful of courageous men and women in Montgomery spearhead a protest movement; they also nurtured, influenced, and helped launch King’s public ministry. A closer examination of the Montgomery movement reveals how a young English professor at Alabama State University (Jo Ann Robinson) and a middle- aged Pullman porter (E. D. Nixon) played a larger role in King’s civil rights leadership than a white theologian like Reinhold Niebuhr or a global leader like Mahatma Gandhi. This book demonstrates how Mont- gomery and her people provided the true birthplace of Martin Luther 2 King’s civil rights leadership. 1

2 BECOMING KING In an essay published over a decade ago, Charles Payne argued that the story of the Montgomery movement needed to be retold. Contrary to the top-down, King-centered narrative of the boycott, Payne suggested that “Montgomery was largely a willed phenomenon, a history made by everyday people who were willing to do their spadework, not one shaped entirely by impersonal social forces or great individual leadership.” Assert- ing that many studies were “more theatrical than instructive,” he charged that “the popular conception of Montgomery—a tired woman refused to give up her seat and a prophet rose up to lead the grateful masses—is a good story but useless history.” This book attempts to be both a good story and useful history by emphasizing the contributions of many men 3 and women, black and white, to Montgomery’s local struggle. A more in-depth analysis of Montgomery in the 1950s demands a significant examination of the very real class differences in the African American community. Most local black leaders prior to the boycott be- lieved the masses were passive and unwilling to get involved in any signifi- cant effort to bring change to their city. The rapid and nearly unanimous response by the working class to the call for a bus boycott contradicts this assessment. In reality, most blacks who organized to dismantle segrega- tion were professionals who did not really know much about the daily lives or the thoughts of their town’s working-class blacks. By contrast, E. D. Nixon was a local leader who knew the so-called “black masses” in his city. Nixon worked for decades to improve the conditions facing African American laborers in Montgomery. He coupled a passion for overcoming segregation with a zeal for economic justice. He was not simply seeking an end to racial discrimination; he also sought justice in the courtrooms and economic opportunities that would extend to all of the black community. Conditions on city buses galvanized African American leaders and professionals along with the working class, resulting in an incredibly ef- fective thirteen-month protest. Black professionals were ready to orga- nize in an effort to win an ideological battle against white supremacy by insisting whites treat their race with dignity. Working-class people who actually rode the buses each day were tired of the abuse and mistreatment they experienced directly. The people were ready to act, and their protest captured the attention of the nation and the world. A year later, they cel- ebrated the end of segregated buses in Montgomery.

Prologue 3 Most studies of Montgomery and the broader civil rights movement tend to leave the city’s struggle behind after the conclusion of the boy- cott and the launching of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Even works that take very seriously the contributions of many local men and women years before the boycott do not explore what happened in the city between 1957 and the end of the decade. This book, however, examines the lack of a sustained movement and the absence of economic gains after the dawn of integrated buses. Although King gained a great deal from his experiences in Montgomery, the city itself remained seg- regated and racially repressive long after King returned to Atlanta. King friend and Alabama State College professor Lawrence Reddick claimed a year after the boycott that the true test of success for Montgomery was not “found in what it has done for the Negro community in this city” but rather through its “positive national and international effect.” The Mont- gomery movement provided a stepping-stone for a growing national civil rights movement, but its sustained local impact on the daily lives of black 4 citizens from all socioeconomic classes was minimal. King’s role, influence, and development remain an important part of the Montgomery story and the broader civil rights movement. While many more studies of local struggles are essential, there is also a need for the leaders and institutions of the movement to be understood through the lens of local communities. Glenn Eskew, in his work on the free- dom struggle in Birmingham, includes a reexamination of King from the perspective of the people who participated in perhaps the most signifi- cant campaign of the era. In this book, instead of viewing Montgomery through the lens of King’s leadership, his leadership is explored through the lens of the civil rights struggle in Montgomery. Such an approach underscores King’s ability to connect with the educated and the unlet- tered, professionals and the working class. This also allows for a sharper critique of the shortcomings of King’s leadership following the bus pro- test, limitations he would not address until the last few years of his life. As the boycott came to an end, King’s inner circle began to be dominated by clergy and a few college professors who turned their focus to voter regis- tration efforts and better recreation facilities. E. D. Nixon’s concern for sustained economic development and job creation was left behind, as was the original boycott demand for black bus drivers. Although King main-

4 BECOMING KING tained an ability to listen to and speak the language of the working class, following the boycott his approach to the freedom struggle was defined 5 more by professionals and clergy than by working-class activists. By examining King’s activities after the boycott through the lens of Montgomery, one sees how he slowly disengaged from the local struggle. While maintaining symbolic leadership as the president of the Montgom- ery Improvement Association, King’s energies drifted more and more to the broader regional struggle. Elevated to national prominence by the success of the boycott, King used his impressive resume, oratorical gifts, and tactical skills to contribute to other local movements. He would never again be as intimately connected to local activists as he was in Montgom- ery. His elevated status led to criticisms of his leadership, with members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee referring to King de- risively as “de Lawd” by 1962. Five years earlier, King had already begun to disengage from the only local movement to which he had a true grass- roots connection. The strong pull of the regional and national platform eclipsed his efforts in Montgomery, where due to white intransigence and violence as well as reemerging divisions within the black community, moving forward proved tedious and tiring. By understanding the more complete story of Montgomery, one gains a better understanding of the 6 strengths and limitations of King’s civil rights leadership. The local movement also demonstrates the indispensable contribu- tions of women in the struggle for civil rights. Many early histories of the civil rights era emphasized the significance of male leaders while failing to recognize the efforts of female leaders. Jo Ann Robinson’s memoir on the Montgomery movement helped correct this omission. Women in the Civil Rights Movement, a volume of essays published in the early 1990s, furthered the effort to emphasize the critical contributions of women like Robinson, Rosa Parks, Fannie Lou Hamer, Mary Fair Burks, and Ella Baker. A close look at Montgomery from 1948 to 1960 continues this important effort by demonstrating not only the significance of white and black women to the local struggle, but also the influence they had on 7 King’s development. Scholars have recognized the church-based and religious roots of the civil rights movement for decades. Many of the leaders were black clergy; mass meetings tended to take place in local congregations; and one of

Prologue 5 the leading organizations pushing for social change in the South was the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Recent studies have explored in greater depth the way religion, theology, and the church helped inspire and define the struggle. By examining the earliest sermons and religious writings of King before, during, and after the boycott, this work high- lights the significant and sustained theological underpinnings that help explain why King had the influence and following that he did. King’s optimistic, hope-filled message rooted in the power of God inspired men and women to remain in and sacrifice for the struggle. His consistent emphasis on the love ethic found in the life and teachings of Jesus pro- vided the theological undergirding for the strategy of nonviolence. King’s growing faith in God also fueled his conviction that the civil rights move- ment could become a vehicle for redemption in Montgomery, the South, 8 and throughout the nation. As a Baptist minister, King delivered sermons that provide an excel- lent window into his thought and development as a leader. Through the Martin Luther King Jr. Papers Project, hundreds of King’s early homi- letic manuscripts, outlines, and recorded sermons are now available to researchers through the publication of their latest volume. These reli- gious writings demonstrate more clearly the theological commitments King brought to Montgomery. King’s oratorical skills coupled with a pas- sionate commitment to the power of love and the centrality of the social gospel allowed him to be the ideal spokesperson and leader for the Mont- gomery movement. Years before the boycott, King was already regularly addressing issues of race, segregation, peace, and economic injustice from the pulpit. The core of King’s message stayed consistent throughout his 9 adult life. By 1954, King and Montgomery were ready for each other. Montgomery demonstrates that King’s sermons and speeches be- came most poignant when accompanied by direct action, something he was willing to participate in, but not something he ever initiated. Taylor Branch, in his three-part series on King’s public career, concludes that King’s inclination was to inspire social change through oratory. Following the bus boycott, he was unsure where the movement should go next, and “under these conditions, oratory grew upon him like a narcotic.” Unable to effectively transfer the model of the bus boycott to address other lo- cal challenges or broader regional injustice, King replaced nonviolent di-

6 BECOMING KING rect action with public speaking. Branch concludes that “this conversion approach had brought King the orator’s nectar—applause, admiration, and credit for quite a few tearful if temporary changes of heart—but in everyday life Negroes remained a segregated people, invisible or menial specimens except for celebrity aberrations such as King himself.” Follow- ing the boycott, it was not until the advent of the sit-in movement, the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and the demonstration of courage by the Freedom Riders that the civil rights movement became a national phenomenon. These and subsequent local movements, buttressed by King’s oratory and symbolic leadership, transformed the civil rights struggle into a regional civil rights movement that changed a nation. Without the courage and sacrifice of countless men and women from Montgomery to Greensboro and from Nashville to Birmingham, King’s “I have a dream” speech would have fallen on deaf ears. King’s oratory had its full potency only when accompanied by 10 concrete engagement. The March on Washington was not the first time King learned both the limits and possibilities of the spoken word. King’s first oratorical tri- umph, his Holt Street address delivered on the first day of the boycott, emerged only because of the fifty thousand African Americans who did not ride Montgomery’s buses that day. In the speech, King claimed that the people gathered at Holt Street Baptist Church “because of our deep- seated belief that democracy transformed from thin paper to thick ac- tion is the greatest form of government on earth.” King experienced the 11 power of oratory coupled with “thick action” first in Montgomery. When King’s sermons at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church between 1954 and 1960 are put in conversation with historical events chronicled through numerous oral histories, newspaper articles, and archival mate- rial, they reveal a growing passion, urgency, and faith forged in the midst of struggle. The fortitude of Montgomery activists such as E. D. Nixon, Jo Ann Robinson, Rufus Lewis, Mary Fair Burks, and Rosa Parks had a significant impact on King’s early public ministry. Local grassroots lead- ers helped refine King’s early experiences as they joined together in a prolonged struggle against white supremacy. This study is structured chronologically. Chapter 1 examines the story of Montgomery from 1948 to 1953, demonstrating that years be-

Prologue 7 fore King arrived in the Alabama capital, several black and white men and women were challenging segregation and white supremacy in their city. Chapter 2 explores King’s ministry and theological development be- fore he became pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. By the time he preached his first sermon at Dexter, King had already crafted a socially engaged understanding of Christianity that would form the heart of the social gospel he would preach throughout his public ministry. Chapter 3 reviews King’s tenure in Montgomery prior to the bus boycott. He joined many in the city who, as Rosa Parks put it, were “hoping to make a contribution to the fulfillment of complete freedom for all people.” Through involvement in the NAACP and his activities as pastor of Dex- 12 ter, King supported the local movement before the boycott began. The fourth chapter concerns the first two months of the boycott, con- cluding with the bombing of King’s home on January 30, 1956. Chapter 5 explores how King and the broader community responded to threats, violence, and legal maneuvers over the last ten months of the boycott. The sixth chapter examines how King gradually turned his attention away from Montgomery during his last three years at Dexter. By the time King departed the city, his focus had shifted to the national stage, to a struggle bigger than Montgomery. Many of those who predated King in Montgomery faced difficult days as the local movement faltered. In the final analysis, the bus boycott did more for King and the emerging national civil rights movement than it did for the broader African American community in Montgomery. King took the lessons of Montgomery with him, as their courage, activism, and sacrifice prepared him for the many battles that awaited him. In the crucible of Montgomery, Martin Luther King Jr. was becoming King the civil rights leader.

1 “The Stirring of the Water” I think the Negroes are stirring and they won’t be held down much longer. —Virginia Durr, 1951 Racially integrated events rarely occurred in Montgomery, but for sev- eral years both whites and blacks gathered together at the city’s spacious Cramton Bowl for an Easter sunrise celebration. Segregated seating ap- plied at the municipal arena, but the all-white planning committee worked to include African American preachers in the program as they developed the service. Typically a black minister delivered a prayer and an African American choral group from a local school led the audience in a few tra- ditional spirituals while whites presented the balance of the program, in- cluding the sermon. The 1952 gathering proved to be the last, however. Despite steady rainfall, city bus drivers found it more convenient to drop off their black passengers several blocks from the entrance to the event. Even if the weather had not dampened spirits, the discourteous treatment they experienced at the hands of the bus drivers certainly did. Some did not stay for the service, and many more lobbied their ministers to put together all-black sunrise services in the future. Portia Trenholm, the wife of the president of Alabama State College, claimed this was “the very first spontaneous protest as a result of discourteous treatment on the buses.” The following year the black clergy bowed out of the planning process, and African Americans attended a separate sunrise service on the Alabama 1 State College campus. This act of protest on the part of the black citizenry of Montgomery reveals their willingness to act collectively to resist mistreatment at the hands of white bus drivers. While this action may have seemed incon- sequential at the time, it demonstrates a discernible spirit of resistance among African Americans in the city by the middle of the twentieth cen- 9

10 BECOMING KING tury. Years before Martin Luther King Jr. arrived in Montgomery, a hand- ful of whites and many blacks shared a growing dissatisfaction with the racial status quo. Several were already hard at work testing strategies of resistance to segregation. The ranks of those questioning and even challenging Montgomery’s racial mores near the middle of the twentieth century were diverse. While demeaning experiences due to segregation concerned the entire African American community, leaders broadened their civil rights agenda to in- clude broader economic concerns. Specifically, Dexter Avenue pastor Ver- non Johns, Pullman porter E. D. Nixon, and seamstress Rosa Parks not only challenged the physical markers of white supremacy evidenced by segregation, but also questioned the more insidious and diffuse economic oppression that gravely influenced the lives of poor and working-class African Americans. While their agendas were not uniform, several men and women had already decided their days of quiet submission under segregation were over years before King ever set foot in the city. Though their methods and philosophies differed, several were actively stirring the 2 waters in Montgomery. Montgomery sits on the Alabama River in the heart of the Black Belt, a land with rich soil, a heritage of bountiful cotton crops, and a legacy of slavery. In addition to its role as a major marketplace for the sale and distribution of cotton, the city also serves as the state capital. The community’s investment in the institution of slavery made it a hotbed of southern political maneuvering following the election of Abraham Lin- coln. When southern voices arguing for secession from the United States prevailed, Montgomery was chosen to host a convention of slave states. Following the Civil War, the city continued to depend upon cotton from hinterland plantations to fuel the economy. Many former slaves transi- tioned to either tenant farming or sharecropping, and as a result cotton production remained the economic bellwether for the region. Thanks to a combination of state government jobs and the region’s rich agri- cultural land, Montgomery did not aggressively pursue industrialization. The city’s economy during the twentieth century was shaped more by 3 advances in aviation than in industrialization. A few years after their first flight, Wilbur and Orville Wright searched for a place to train prospective pilots during the colder winter months.

“The Stirring of the Water” 11 They selected a site on the outskirts of Montgomery, which became known as Maxwell Field. While the training school was relatively short- lived, aviation remained a permanent feature of the city’s economy. Over the coming decades, Montgomery became home to two air force bases, 4 introducing a reliance on the federal government into the local economy. The increase in military personnel reshaped the city’s job market and demographics. Following the Civil War, African Americans outnumbered whites until around 1910, by which time whites had pulled even with blacks. The white population continued to grow more rapidly over the next forty years, resulting in a 1950 population of more than 110,000, with roughly 60 percent white. This increase can be attributed to an in- flux of working-class whites who greatly reshaped municipal politics as the old political machine slowly lost control of the city. The military em- ployed hundreds of Montgomery’s new residents, who had no ties to historically elite families that had monopolized local political power. The city leaders’ failure to attract and develop major manufacturing further weakened their hold. The populist Dave Birmingham capitalized on this growing distrust of political leaders in his 1953 campaign for a seat on the city commission. He went so far as to accuse politicians and city fathers of poisoning the city water supply, a claim that resonated with the suspicions of some of the town’s newer residents. With the support of an effective al- liance of a few registered African Americans and the white working class, Birmingham shocked the establishment with his election to the city com- mission. New political realities were but one indication that the city was 5 undergoing significant social change. The economy and social structure of Montgomery depended upon the affordable service labor of the region’s African American men and women. In the late 1950s, Baptist minister Ralph Abernathy estimated that service-oriented occupations accounted for 75–80 percent of the Af- rican American workforce. Approximately two-thirds of the black women in the area found employment as domestic workers. The lack of alterna- tive industrial jobs significantly limited their earning potential. According to the 1950 U.S. Census, the median family income for African Ameri- cans in Montgomery in 1949 was $908, while in Birmingham, where the availability of industrial jobs bolstered the earning power of black resi- dents, the median income was $1,609. While a small percentage of the

12 BECOMING KING city’s black population held professional jobs, primarily in the education field or the military, the lack of industrial jobs made the gap between the classes in Montgomery’s African American community particularly acute. The limited economy contributed to the stifling experience of life under 6 white control for many of the city’s African Americans. Kathy Dunn Jackson, who grew up in Montgomery during the 1940s and 1950s, still remembers the dehumanizing treatment she received when she had to have her tonsils and adenoids removed as a young child. Since there were no African American ear, nose, and throat doctors in the city, she had to have her surgery at St. Margaret’s Hospital, which did not allow blacks to have a room in the main building following their surgery. Instead, hospital orderlies moved Jackson to a room shared with all the hospital’s black patients in a small house behind the hospital. In follow-up visits with her doctor, she had to wait in a “colored” waiting room that doubled as a janitorial closet. Jackson’s memories are indicative of the dehumanizing events that were all too common in Montgomery 7 during the decade following World War II. Given the insidious nature of Montgomery’s racism and segregation, it appeared that white supremacy was firmly in place. Further examina- tion, however, reveals the presence of subtle changes in racial mores. A front-page article in the Alabama Tribune indicated “race plates” (a prac- tice whereby a letter C was placed next to names of African Americans) would be dropped from the Montgomery phone directory. The rationale for the change, according to a company representative, was “to avoid dis- crimination against Negro people.” He indicated that all married women, regardless of race, would be given the title “mRs.” before their names. In addition to this symbolic change, significant services for African Ameri- cans also expanded. Montgomery established two black high schools: Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver High. St. Jude’s Hospital opened, marking the first hospital for blacks in the city. Local white leaders provided these expanding services for African Americans within the framework of white supremacy and segregation. While easier access to quality medical care and education directly enhanced the daily lives of Montgomery’s African American citizens, these services did not ameliorate the dehumanizing pall of segregation and economic marginal- ization they continued to face. Even though President Harry S. Truman’s

“The Stirring of the Water” 13 1948 Executive Order integrating the armed forces provided an oasis of growing inclusion at Maxwell Air Force Base, African Americans who 8 worked there returned each evening to a segregated southern city. As Montgomery’s African Americans gained access to additional com- munity services and institutions, their challenges to overt racism expand- ed. Protests following incidents of police brutality even led a few whites to question unwarranted violence by police against African Americans. When Montgomery police mercilessly beat an African American, Robert Felder, so severely that he was hospitalized for several weeks, his white employer took the unusual step of reporting the incident to the press. Police chief Ralph B. King dismissed the officers involved, but he paid a price for his diligence. Bowing to public pressure, the city commissioners forced Chief King to retire. A few years later, the police arrested Gertrude Perkins on a charge of public drunkenness. Rather than transporting her to the police station, the arresting officers took her to a remote loca- tion where they raped her. When the incident came to light, police chief Carlisle E. Johnstone vigorously pursued harsh reprimands and even the prosecution of the officers involved. Once again, the city commission did not back their police chief. The mayor accused the NAACP of fabricating the whole story, and police records were altered to protect the identities of the accused rapists. When city authorities ignored his recommenda- tions, Chief Johnstone began searching for a job in another community 9 and soon left the city. Police brutality against African Americans went even further one hot August afternoon, when an intoxicated World War II veteran named Hill- iard Brooks attempted to ride a Montgomery bus. Driver C. L. Hood would not allow him to board, but Brooks refused to back down and unleashed a string of obscenities. When the police officer M. E. Mills arrived on the scene, he pushed Brooks to the ground and fired a fatal shot when Brooks scrambled to get back up. Alabama State professor Jo Ann Robinson recalled that Brooks simply got “out of place” with the Following a protest by friends of bus driver and paid the ultimate price. Brooks, a police review board found the officer’s actions justified, an as- sessment endorsed by the mayor. While a few whites and many African Americans questioned the violence and abuse visited upon African Ameri- cans, city officials continued to sanction excessive force by police officers.

14 BECOMING KING Those rare local white leaders willing to voice concerns and challenge the racial status quo did not last long in Montgomery. African American acts of resistance seemed to be making little headway. Still, the challenges themselves demonstrate the willingness of some to take risks to challenge 10 white supremacy. Despite the persistence of racial repression, black institutions of high- er learning remained a vibrant force in the region. Tuskegee Institute, a black normal school just thirty miles east of Montgomery, was founded by Booker T. Washington in 1881. Under his leadership, the school focused on industrial education while attempting to accommodate the wishes of southern white authorities to maintain a segregated society. The faculty of the school became part of a small but growing black middle class in the region. By the 1930s, the advent of the automobile had dramatically reduced the travel time between Tuskegee and the state capital, allowing the school’s faculty to become regular visitors to Montgomery for shop- 11 ping and cultural events. Alabama State College (ASC), which sat right in the heart of Mont- gomery, had an even greater influence on the city. Originally a normal school located in Marian, Alabama, the institution moved to Montgom- ery in 1886. By the middle of the twentieth century, the college had nearly two thousand students and employed two hundred faculty and staff members. ASC’s president was H. Councill Trenholm, who at the age of twenty-five succeeded his father in 1925. Under his leadership through 1961, the school grew from a junior college to a four-year insti- tution, and began to bestow graduate degrees in 1940. Trenholm worked to carefully balance fidelity to the concerns of African Americans with the expectations of the white government officials who helped fund the school. On the twenty-fifth anniversary of his presidency, Professor Jo Ann Robinson penned a letter of congratulations to Trenholm: “It is my belief that true greatness can be measured only in terms of services one renders to humanity. If this is any criterion, you are one of the few truly 12 great and I respect and admire you for it.” Careful to avoid controversy, Trenholm earned the admiration of blacks and whites. His stewardship of ASC provided a haven for educated African American leaders in Montgomery. Many of the employees at ASC knew their jobs were tied to state government subsidies of their school.

“The Stirring of the Water” 15 Most followed Trenholm’s lead in cautiously interacting with white lead- ers, as they sought to better their lives and social standing through com- promise. ASC employees and graduates helped provide Montgomery with a growing black middle-class community. In addition to black colleges, the NAACP had been active since the institution of a local chapter in 1918. The following year, the state chap- ter met in the basement of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in an effort to get state authorities to take a strong stand against lynching and to improve educational opportunities for blacks. The NAACP was also ac- tive in voter registration efforts, and the organization served to bring together many seeking racial justice in the Montgomery area, including a Pullman porter named E. D. Nixon. As a member of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters under the leadership of A. Philip Randolph, Nixon earned a reputation as a tireless fighter for justice and social change. He also became the person to whom working-class blacks went when they had significant issues with the courts or local government officials. The Montgomery chapter of the NAACP, however, was more often than not dominated by moderate professional blacks who preferred a cautious ap- proach to racial advancement. As one local resident noted, the organiza- tion was actively involved in the community, “but not very much really to get down to the masses of the people—just the top layer of the Negroes.” Many ASC faculty and a few local clergy participated in the local chapter, resulting in an organization that relied on a deliberate legal strategy that 13 was largely nonconfrontational. During the mid 1940s, the local NAACP elections proved to be a battlefield as segments of the African American community competed with one another for control of this significant civil rights organization. In December 1944, Nixon decided to run for president of the local chap- ter, facing Robert Matthews, who worked for Pilgrim Insurance Com- pany. Matthews won the election by just a few votes, prompting Nixon to compose a letter of protest to Walter White in the NAACP national office. According to Nixon, Matthews triumphed through illegal means, stuffing the ballot box with the ballots of fellow employees of Pilgrim Insurance who only showed up once a year for the election. Although indignant over how the election was conducted, Nixon claimed his true concern was for the people of Montgomery, as Matthews was not “qualified for

16 BECOMING KING the office” and “is afraid to oppose white people when he knows that they are wrong.” Unlike Matthews, others in the city were laboring to bring change and reform: “all the work that has been done in Montgomery for the pass [sic] year was done by Mr. W. G. Porter [NAACP vice president], Mrs. Rosa L. Parks, and myself.” In a handwritten postscript to the typed letter, Nixon shared what his platform would have included had he been elected, emphasizing that under his leadership the NAACP would be “a 14 branch for the people.” Apparently many of Nixon’s concerns regarding Mr. Matthews’s leadership had merit. Donald Jones, a NAACP national representative, visited the city in May 1945. Following his visit, Jones composed a let- ter to Ella Baker, who was serving as the director of branches for the NAACP. Jones concluded that “the Branch is in a bad way due to a lack of competent leadership not only in the Branch, but apparently in the community as a whole. Usually in a Branch there is at least one individual who stands out, sometimes in the Branch setup and sometimes in opposi- tion; but in Montgomery I found nobody who seemed to have the ca- pacity to do a job.” Jones called Matthews “hopeless” and observed that “besides being incompetent he’s disinterested. The main reason for his being president, it seems, is because he works for the Pilgrim Insurance Company there which has had one of its personal [sic] always as president for the last several terms, obviously for prestige purposes.” The leadership of the NAACP in Montgomery had been reduced to part of a patronage system controlled by a particularly powerful African American–owned business. Nixon’s concerns about the effectiveness of the branch were 15 warranted. Nixon was determined to win the next election for the presidency of the NAACP, and began appealing to potential new members to support his candidacy. He attempted to persuade potential members by calling for “a more militant N.A.A.C.P. in Montgomery, because we need a program to offer the people, because we need to return the N.A.A.C.P. to the people as their organization.” Nixon planned an organizational meeting for October 11, nearly two months before the election, to plan strategy. In a handwritten note at the bottom of one of his form letters, he asked NAACP vice president W. G. Porter to ask Ella Baker for five hundred new membership envelopes as he expected to “need these in my campaign.”

“The Stirring of the Water” 17 In what was described as the best turnout for an election in many years, Nixon was elected as the new president. For a few years, the local chap- ter of the NAACP was under leadership that represented the working- class African Americans in the city. During his tenure as president, Nixon relied on a member of the working class as his secretary, a local seamstress 16 named Rosa Parks. Born and raised near Montgomery, Parks attended a NAACP meet- ing after seeing a picture of her former schoolmate, Mrs. Johnnie Carr, next to a story about the NAACP in a local paper. When Parks arrived at the meeting, not only was her old friend absent, but Parks was the only woman in attendance. The men soon nominated and elected her secre- tary of the chapter. Parks later recalled: “I was too timid to say no. I just started taking minutes.” She began working with Nixon, and supported his leadership of the local and state chapters of the NAACP. She also helped establish and lead the local NAACP Youth Council. When Nixon lost the presidency of the chapter, she took a two-year break from the organization, although she continued to volunteer her time to assist Nixon. After long days working as a seamstress at Crittenden’s Tailor Shop in Montgomery, she would spend the early evening completing essential office tasks for Nixon, who had begun to focus on other activities after his tenure as NAACP president in the late 1940s. Parks was a respectable member of the African American community who worked hard to support her family financially while at the same time laboring tirelessly, often in tandem with 17 Nixon, to bring substantive change to the racial climate in her city. E. D. Nixon led several local organizations over the years, including the Citizens Overall Committee, an attempt to unite Montgomery’s Af- rican Americans to address community challenges. He traced his drive to fight for civil rights to a meeting with the mayor of Montgomery during the 1920s, in which Nixon raised concerns about the safety of a drainage ditch in the city that had recently claimed the lives of two young African American boys. The mayor was not pleased that Nixon had come to city hall with the grievance, and even threatened to throw him in jail. Nixon remembered: “After that incident, I knew there would not be any recre- ation or any form of civil rights for black people unless they were ready and willing to get out and fight for it.” He put this philosophy into action 18 over the following decades.

18 BECOMING KING In addition to the Citizens Overall Committee, Nixon founded the Montgomery Welfare League and also led the Progressive Democratic Action Committee, which Jo Ann Robinson described as “an old, well- established organization of black leaders, men and women. Some of the best political minds in Montgomery were in this group.” Vigilant in his attempts to highlight injustice, Nixon charged in the Alabama Tribune that some counties in Alabama had instituted “quota style racial restric- tions” on African Americans following the 1952 general election, while others had prevented blacks from voting altogether. He further alleged that “5,000 Negroes have been denied the right to register and vote for no other reason than that they are Negroes.” Nixon threatened legal ac- tion to secure the ballot for black citizens in Alabama. He was never afraid to publicly challenge white leaders to ensure full citizenship for himself 19 and all blacks in Alabama. Few African American men in Montgomery displayed the public courage embodied in Nixon’s rhetoric and actions. His union member- ship and associated job security as a Pullman porter ensured his job was secure from the retribution of local whites. Having grown up in poverty and poorly educated, Nixon made a special point to connect with the city’s working-class blacks. He understood the significant socioeconomic needs that plagued many of his friends and neighbors. Through his as- sociation with Randolph and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, Nixon had learned the power of ordinary people joining together for a common cause. He became their advocate, and worked not only to stir the people to action but to alert professional blacks to the dire financial and social conditions facing many in Montgomery. Most middle-class African Americans elected to keep their distance from Nixon, however. While he had some degree of economic indepen- dence, most of them did not. When Nixon walked the streets of down- town Montgomery, he remembered “some of your so-called big people who are close to the white folks” crossing the street to avoid being seen with him. Donald Jones, in his 1945 assessment of the local NAACP chapter, characterized Nixon as “the strongest man in the community in civic affairs, pretty influential among the rank and file,” but he also had reservations about Nixon. Jones thought that Nixon “fancies himself an amateur detective” who was always trying to demonstrate some injustice

“The Stirring of the Water” 19 in the courts toward local African Americans. The letters of correspon- dence between the local branch and the national office of the NAACP during the 1940s help paint a picture of Nixon as a passionate and ag- gressive leader who would not let the slightest injustice or insult go un- challenged. While Nixon’s tenacity was vital for change to happen in the Jim Crow South, his concern over the minutiae of local branch affairs and concerns could prove wearisome for even the most ardent activists. Even Ella Baker seemed to grow weary of Nixon’s detailed appeals to the national office for rulings to solve local disputes. Baker ended one letter to Nixon concerning the use of branch monies for a USO party for returning World War II veterans: “Nevertheless, I do not believe that the money spent for the veterans’ social should be made a major issue.” Although Nixon’s intensity could prove controversial and threatening and even exhausting to those around him, the local pastor Solomon Seay recognized in him “an entwined combination of courage and wisdom. He was well qualified to be standing at the threshold of a change in the 20 course of history.” Despite his bold public stands, Nixon developed a few connections with whites in Montgomery. As early as 1945, he was part of clandestine interracial gatherings at Dexter Avenue Methodist Church, a white con- gregation led by Reverend Andrew Turnipseed. The group met in the middle of the night to avoid reprisals. Many of those who gathered—a group that included ASC professor J. E. Pierce, Tuskegee professor Dean Gomillion, and Southern Farmer editor Gould Beech—played a role in the 1946 populist-inspired gubernatorial campaign of Jim Folsom, who served as Alabama governor from 1947 to 1951 and again from 1955 to 1959. While Turnipseed was not the only white challenging segrega- tion in Montgomery, he claimed no other Methodist ministers publicly supported his efforts: “The other Methodist preachers here that I could count on was none. They had never been in the stirring of the water of While fellow clergy did not support his efforts, a this kind of matter.” handful of former New Deal Democrats in Montgomery brought a vi- 21 brant, if small, white contingent advocating for racial change. Following the death of Franklin Roosevelt in 1945, many connected to his administration began to depart the capital, including Aubrey Wil- liams, who had served as the executive director of the National Youth

20 BECOMING KING Administration. Williams returned to his native Alabama to purchase and run, with the financial backing of Chicago department store mogul Mar- shall Field, the struggling Southern Farmer magazine. He enlisted fellow New Dealer Gould Beech to serve as editor of the monthly paper, which they retooled to espouse populist and racially inclusive positions from its 22 headquarters just outside Montgomery. Given their proximity to the state capital, Williams and Gould could not resist the temptation to get involved in local and state affairs. During one election season, they even worked to find an alternative candidate for the state legislature, which they perceived to be controlled by a racial demagogue. They nominated Steven Busby, an energetic if naïve young candidate. Their goal was for Busby to garner at least 25 percent of the vote, demonstrating the presence of a significant minority of Montgom- ery residents who were eager for change. In the buildup to the election, Beech spoke with Nixon, who agreed to mobilize the grand total of sixty registered black voters behind their candidate. Beech and Williams rallied the liberals in town, including local labor, and surprisingly Busby won the seat. This small victory demonstrated the latent radicalism in Mont- gomery that could effect small changes and have an impact, provided reactionaries were unaware of the possible ramifications. Jim Folsom’s two nonconsecutive terms as governor (1947–51, 1955–59) also reveal the appeal of populist candidates in Alabama. Known as a friend of the working class, Folsom reached out to the small number of black voters in 23 the state and refused to engage in racial demagoguery. Former New Deal Democrats Clifford and Virginia Foster Durr soon joined Williams in Montgomery. Clifford had served as the first director of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) under Roosevelt, while Virginia had been very active in the Southern Conference for Human Welfare (SCHW) and the movement to abolish the poll tax. Following a brief stint in Denver, the couple returned to their native Alabama. Clif- ford established a law practice that counted the Southern Farmer among its clients. Virginia invested some of her time connecting with other like- minded people in the city, including Nixon and Aubrey Williams. The racial mores of Virginia Durr’s home state shocked her after spending nearly two decades away. In a letter penned shortly after her return, she described her response to the “steady and continuous” op-

“The Stirring of the Water” 21 pression of African Americans: “It is like seeing a great stone lying on them—but it lies just as heavily on the white people too—and I feel so continually guilty that I am not doing anything about it.” Despite ex- periencing “constant pain” regarding the racial situation, she believed African Americans were “stirring and they won’t be held down much lon- ger.” As New Deal Democrats who had forged friendships with southern progressives like Myles Horton, James Dombrowski, and Myles Horton, Williams and the Durrs found common ground with Nixon’s agenda to 24 challenge both Jim Crow segregation and economic injustice. Although she felt guilty for not being involved in efforts to challenge segregation, Virginia Durr did develop friendships with a few women, both white and black. An organization called the United Church Women, which held regular interracial prayer meetings in the city, became an im- portant connection point for Durr. Through these meetings, Durr met 25 women like Juliette Morgan, Olive Andrews, and Clara Rutledge. Juliette Morgan was a local white librarian and one of the more out- spoken advocates for a more racially inclusive city and state. In an editorial published in the Montgomery Advertiser, Morgan voiced support for fed- eral action to combat “discrimination against minority groups.” Noting her opinion was in the minority, she added that “Ministers, some editors, social workers, and educators, and other thinking people are speaking out against the savage old mores of the South, otherwise referred to as ‘our Southern traditions.’” She argued that the Democratic Party slogan “White Supremacy” was “an insult to the colored races” and “a disgrace to the white,” adding that “those who insist that the states can handle civil rights are, for the most part, more concerned with maintaining the status quo than they are in securing civil rights for any minority.” While Montgomery tolerated the few who did not support white supremacy as long as they did not become too vocal, Morgan foreshadowed senti- ments that would later be seen as threatening by those committed to 26 segregation. Morgan’s letter drew the attention of James Dombrowski, the presi- dent of the Southern Conference Education Fund. He wrote Morgan to inquire about her editorial, asking how she developed such radical views. In her response, Morgan claimed that her opinions were widely shared in Montgomery, but most were “afraid of speaking out.” To support her