Consulting in a Nutshell

Resources for those interested in the field, already in the field, or those who are simply curious.

What they do: Advise companies on how to grow the business or battle a problem. Economic upheaval is forcing many firms to rethink strategies, creating a need for advisers on everything from pricing and operations to cost-cutting and sales growth. Information technology consulting is one of the fastest-growing areas, as is helping companies explore international markets.

What's to like: Teamwork, project variety, and the satisfaction that comes from solving tough problems. "I love the challenge of a company saying, We want to grow revenues by 20%. How can we do that?' " says Sukanya Soderland, 32, of Oliver Wyman in Boston.

Michael Sherman, 37, of The Boston Consulting Group in Dallas likes that "you get training in a couple years that would take a decade in a corporate setting." Big consulting firms such as McKinsey & Co. may offer higher salaries, boutique firms tend to be more specialized.

What's not to like: Grueling travel schedules, late hours, and punishing deadlines.

Requirements: Just about anybody can claim the title (nearly a third are self-employed), but an MBA coupled with experience inside firms in your field gives you an edge. Nowadays many laid-off managers are finding that their industry knowledge and access to insiders translates well to consulting.

I recently saw (the cheeky puppet musical that tells the story of new college grads) and one of the characters was a lovable, unemployed comedian who was having a hard time finding a job and figuring out what it was that he was good at.

At the end of the play as things started neatly wrapping up for the cast, (spoiler alert) we find out he found a job as a consultant. The NYC crowd in attendance went wild: The insinuation was he had no idea what that meant, but it paid well and heck, even this wanderer could fit in there.

As a consultant, imagine my indignation! So I did what every other normal person in the same situation would do-start fervently whispering my defense of consulting to my friends. For some reason, they didn't seem to care, but now that I have your attention, I'll continue it here.

Honestly, consultants can have a bad reputation. From Kalon, the luxury brand consultant in The Bachelorette, who made his grand entrance onto the show via helicopter (seriously-even I can't defend you, Kalon) to the popular phrase "consultants take your watch and tell you what time it is"-the image isn't always positive. However, the industry has survived despite these stereotypes and it still continues to attract top talent across the world.

Why? While there are many reasons, I attribute it most to the way consulting develops its people. Consultants are exposed to a wide variety of experiences and are taught how to apply lessons learned in other situations to the ones at hand. Moreover, consulting instills in its recruits an extraordinary amount of discipline and technique that they would be hard-pressed to gain at such an intense and focused level elsewhere.

Consulting can offer you incredible experiences and career prospects-but it does also ask for a significant investment of your time and energy. If you're thinking about consulting, here is what you should consider as you make your decision:

1. The TSA agent will know your name and you won't run into Ryan Gosling at the airport

Yes, consultants travel all the time, and no, it's not glamorous. Don't get me wrong: It can be fun at times, and there's a certain amount of self-discovery that occurs when you're eating alone at Cheesecake Factory in some random town, but you have to be prepared that your Monday-Thursday are no longer yours to schedule as you please. You will learn to methodically plan your Friday-Sunday to squeeze in family, friends, doctor's appointments, haircuts, and any other semblance of a personal life. If you're in a relationship or have kids, it makes it even harder to leave that physically behind every week. Of course, most firms try to accommodate special circumstances, but travel is still a major part of the job description.

You'll find ways to make it fun, though. Frequent flyer on Delta and Platinum status at Starwood Hotels? Don't mind if I do!

2. Flexibility is not only a requirement for yoga

When I worked in industry (that's consultant-speak for non-consulting jobs), I'd write myself a to-do list for the day, and more often than not, I'd do just that. I enjoyed the specific, tangible work we did and I developed a close relationship with the people I worked with and for.

Fast forward to consulting, where I can barely plan my schedule for the next week, I have yet to see again people I worked with during my first few months, and the work I'm doing includes everything from financial analysis projects to IT assessments. Recently, I found myself ending a week discussing the Affordable Care Act and it's stipulation around Health Insurance Exchanges, then beginning the next talking about metadata and its proposed structure within a technology.

Consulting can be a great way to gain expertise in all kinds of areas-but it also means that you have to constantly adapt and be as flexible as possible with your aptitude, time, and work style.

3. Dust off your elevator pitch

Consulting is really the art of making connections-not only in terms of the work, but perhaps more importantly, with people. Developing solid networks, both internally at the firm and externally at the client, is crucial. Within consulting firms and on client sites, you are constantly convincing (and proving) to new people that you are and would be a valuable asset to a project.

The job also requires you to share ideas, explain concepts, and present findings almost on a daily basis. You'll be working on teams of people you may have just met, but you must show clients a united front forged from the fires of Mount Doom to ensure that their projects will be executed seamlessly. If you run into the SVP in the elevator and she casually asks how your team's recommendations are coming along, you're going to want to make sure you can calmly summarize things the same way your teammate did when she met with her peers that morning-or five minutes ago.

I don't mean to imply that introverts need not apply (one of my firm's most well-liked and admired partners is a self-proclaimed introvert), but you will have to learn how to push yourself out of your comfort zone and become an effective communicator like she has.

4. Start your engines

This one isn't consulting-specific by any means, but I think is important to highlight here. It can be easy to get lost in the mass stampede of Type A personalities you'll typically see at consulting firms, especially the big ones. To set yourself apart, you have to be a self-starter and know how to efficiently manage your time.

There's no dearth of opportunities within firms waiting for you to seek them out-somewhere to volunteer, some proposal to write, some article to contribute to-but that, combined with your client work, can equal some late nights and long weekends at the office. (I've found myself burning the midnight oil with a Chipotle burrito wilting at my side more than once.) It can be intense and overwhelming, and it's easy to feel burnt out quickly. But finding the balance between asking for new experiences, managing your time, and preparing for the occasional long night or weekend will help you take full advantage of consulting.

Consulting will help you develop a great number of skills (including how to use a delayed flight to your advantage). You will be constantly challenged and asked to do things that you may never have done before. But remember, contrary to what Avenue Q will tell you, it requires more than just the desire to do it to succeed.

This article was originally published on The Daily Muse. For more from the consulting mini-series, check out:- Ace the Case: 7 Steps to Cracking Your Consulting Interview

- Secrets for Cracking the Quant Interview

- 4 Ways Working With Consultants Can Boost Your Career

Photo of consultants courtesy of Shutterstock.

Companies & Industries

Good news for U.S. management consultants: An overwhelming percentage of clients plan to keep hiring them.

Over the next 12 months, 82 percent of the U.S. clients surveyed by market researcher Source Information Services say they won't cut the amount they spend on outside help. And nearly half, 42 percent, plan to bring in even more consultants, while 5 percent expect to boost their spending on consultants by more than 50 percent.

Pressure among clients to keep head count low is stimulating growth for consulting firms-at least for the short term, says Fiona Czerniawska, founder of Source. But as the economy rebounds, she says clients may start to "relax head-count restrictions," dampening that source of growth.

The research organization surveyed 250 U.S. consulting clients (mostly at the C-suite level) and conducted in-depth interviews with another 50 executives.

The U.S. market for management consulting grew 8.5 percent last year, to $39.3 billion. The fastest-growing areas: marketing and sales (25.6 percent), operational improvement (11.3 percent), and technology (10.1 percent). High-growth industry sectors include: health care (18.4 percent), energy (12 percent), and pharmaceuticals (10.3 percent). "After a difficult few years, things are finally getting back on track," the report states.

Where do U.S. companies need help? Not surprisingly, digitization is high on the list, which the research firm says is benefiting consulting companies , Deloitte, and , leaders in this area. "Where the rest of the world talks about globalization, America talks about digitization," according to the report.

U.S. companies, however, are spending much less on strategy consulting. That sector is expected to grow just 3.7 percent next year, not good news for McKinsey, Bain, and other leading strategy specialists. Look for those firms to continue to diversify into other areas, such as implementation and organizational design, as well as tech. "It's hard to separate technology from strategy these days," says Czerniawska.

The survey had something else for U.S consultants to ponder: If consulting companies halve their fees, 59 percent of the clients surveyed would "buy a lot more consulting."

Don't expect consulting firms to start slashing fees, however. "That's a cul de sac you can't get out of," says Czerniawska. What that response suggests, she says, is the inelasticity of consulting prices, because it would take a huge cut to stimulate growth. Rather, she points out, consultants should focus on communicating the value they add and differentiating themselves from competitors. That's advice every management consultant can easily grok.

ELITE management consultancies shun the spotlight. They hardly advertise: everyone who might hire them already knows their names. The Manhattan office that houses McKinsey & Company does not trumpet the fact in its lobby. At Bain & Company's recent partner meeting at a Maryland hotel, signs and name-tags carried a discreet logo, but no mention of Bain. The Boston Consulting Group (BCG), which announced growing revenues in a quiet press release in April, counts as the braggart of the bunch.

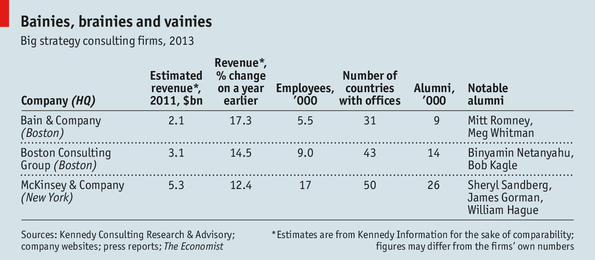

Consultants have a lot to smile about (see table). The leading three strategy consultancies have seen years of double-digit growth despite global economic gloom. In 2011, the last year for which Kennedy Information, a consulting-research group, has comparable revenue numbers, Bain grew by 17.3%, BCG by 14.5% and McKinsey by 12.4%. All three are opening new offices.

Big trends that befuddle clients mean big money for clever consultants. Barack Obama's gazillion-page health reform has boosted health-care consulting; firms would rather pay up than read the blasted thing. The Dodd-Frank financial reform has done the same for financial-sector work. Energy and technology are hot, too.

Companies are reluctant to talk about their use of consultants, and consultancies are relentlessly tight-lipped. Bain is said to use code-names for clients even in internal discussions. Such secrecy makes this a hard industry to analyse.

It also lets stereotypes flourish. McKinseyites are said to be "vainies" (who come and lecture clients on the McKinsey way). BCG people are "brainies" (who spout academic theory). And the "Bainies" have a reputation for throwing bodies at delivering quick bottom-line results for clients.

In fact, the big three all learn from each other. All three now use their alumni networks to gather intelligence and generate business-something McKinsey is famous for. All three stake some of their fees on the success of their projects, a practice once associated with Bain. And all three show off their big ideas to the wider public, as BCG's founder was once among the few to do.

Consulting is no licence to make easy money. Cynics sneer that clients spend millions on consultants only to give the boss an excuse to do what he planned to do anyway. But that would be implausibly wasteful in these days of tight budgets. Consultants today cannot just deliver a slideshow and pocket fat fees. Even the elite three now make most of their revenue from implementing ideas, from finding ways to improve clients' internal processes and from other tasks not traditionally considered "strategy consulting".

As the elite firms move down into implementation and operations, they are meeting big new rivals hoping to move up into the loftier realms of strategy. Over the weekend of May 4th-5th partners at Roland Berger, a mid-tier consultancy, met to discuss a possible buyer for their firm. The most likely candidates are thought to be PwC, Deloitte and Ernst & Young, three of the "Big Four" accounting firms (the other is KPMG).

The big accountancy firms now do more consulting than McKinsey, BCG and Bain. Much of this involves manpower-intensive tasks such as technology integration. But their strategy and operations practices are ambitious, too. In January Deloitte bought Monitor, a brainy strategy firm, out of bankruptcy. In 2011 PwC bought PTRM, a respected operations consultancy. All four have scooped up smaller firms too. A successful Big Four bid for Roland Berger would reopen an old question: can the Big Four crack the elite tier?

It is too early to know whether the brainboxes of Monitor will fit comfortably into the Deloitte juggernaut. When EDS, a computer-equipment and services provider, bought A.T. Kearney, a midsized strategy firm, cultures clashed calamitously. A.T. Kearney bought itself free in 2006.

Nonetheless, Mike Canning, the head of Deloitte's strategy consulting in America, says the Monitor integration is going smoothly, and that clients are showing new interest in Deloitte. Is Deloitte competing with McKinsey, Bain and BCG for work? "Day in, day out, on a regular basis," says Mr Canning. Dana McIlwain of PwC echoes that: "We are definitely competing today, and only more so in the future."

Bob Bechek, Bain's boss, puts it differently: competition with the Big Four is up "very slightly in the past few years, but I mean like a couple of percentage points". He salutes the Big Four: they do what they do well and profitably. But he argues that the heavy-lift, repeatable work at which they excel is a different kind of business. Strategy consultants concoct novel solutions to unique problems, which is hard.

Rich Lesser, BCG's boss, acknowledges the challenge from the Big Four, but is confident. Having new rivals is nothing new, he says. Tom Rodenhauser of Kennedy Information reckons that the Big Four "are cracking the C-suite, but they're not first on the speed-dial for strategy work".

The elite firms are keen not to seem complacent. While boasting about opening offices in Bogotá or Addis Ababa they acknowledge that emerging-world bosses are not blown away by flashy names. The consultants aim to win trust with quick projects that show bottom-line results, before looking to book longer engagements.

Clients in the rich world are changing, too. Fifteen years ago Indra Nooyi, then the head of strategy (now the boss) at PepsiCo, was a demanding client for consultants, having been one herself at BCG. She was a rarity at the time. No longer: the consultancies have seen many of their alumni go on to fill senior positions at big companies.

Some, such as McKinsey, make it easy for big firms to poach their people, by putting potential employers directly in touch with consultants who tick the right boxes for a vacancy. The idea is that this outplacement service makes McKinsey a more attractive place to work. It also keeps the talent churning, constantly refreshing the firm's intellectual capital.

Clients are increasingly demanding specific expertise, not just raw brainpower. McKinsey and BCG, in particular, are hiring more scientists, doctors and mid-career industry types, and reducing the proportion of new MBAs in their ranks.

Vainie: "Vidi, vici"

The firms spend big sums on "thought leadership": ie, papers, books and conferences. This is not all airy-fairy theory. McKinsey has invested heavily in proprietary data. Its boss, Dominic Barton, says: "With the push of a button we can identify the top 50 cities in the world where diapers will likely be sold over the next ten years." The firm invests $400m a year on "knowledge development", and Mr Barton touts its "university-like capabilities" to impart it to its consultants.

It is fashionable to complain that consultants "steal your watch and then tell you the time", as one book put it. But customers clearly value what the consultants offer. Otherwise, the elite three and the Big Four would not be growing so fast.

Things are harder for the next tier, however. Old firms such as A.T. Kearney and Booz & Company (which considered but abandoned the idea of a merger in 2010) are seen by some potential clients as too small to bestride the globe but too big to be nimble. They will watch Roland Berger's fate with interest.

Correction: In the original version of this article the table mistakenly claimed that Boston Consulting Group has 6,200 employees. It actually has around 9,000 employees of which about 6,200 are consultants. This was corrected on May 14th. Our apologies.

WHEN times are good, they are very, very good for consultants. But when they are bad, they are horrid. As the economy stalled in 2009, the global consulting industry shrank by 9.1%. It was the worst year since at least 1982, according to Kennedy Information, an industry monitor.

Now the kids are back in the conference rooms. Companies that shelved plans during the recession are dusting them off and looking for help. And the work is more cheerful. When bosses did hire consultants in 2009, 87% of projects were aimed at cutting costs rather than boosting growth, says Kennedy. This year, just 47% of project spending will be on cutting costs. The rest will go on growth plans, from mergers to installing new computer systems. But not all will benefit equally.

Consulting is a diverse industry. Best known are the elite strategy consultancies such as McKinsey & Co, the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) and Bain. Firms such as AT Kearney, Booz & Company and Oliver Wyman do the same sort of work but are smaller. A second category comprises the consulting units of the Big Four accounting firms-PwC, Deloitte, KPMG and Ernst & Young. All but Deloitte shed their consulting units in the early 2000s, amid post-Enron fears of conflict- of-interest, but have since grown new ones. A third group consists of technology firms with big consulting businesses, such as IBM and Hewlett-Packard, which focus on installing and integrating computer systems. Finally, some consultants are hard to distinguish from pure outsourcing firms.

Strategy consulting, the most famous variety, is also the most controversial. "I like to con people. And I like to insult people. If you combine "con" and "insult", you get consult," observes Dogbert, a comic-strip character. Many firms share this harsh view of the highly paid advisers who walk in and tell them to re-invent their businesses. Spending on strategy consulting is expected to grow by an annual average of just 1.1% to 2014 (it currently accounts for 12% of all spending on consulting).

But more mundane work is booming. Kennedy forecasts that consulting on operations-management (advice on how to do the same things better) will grow by 5.1% a year, that on IT by 3.9% and that on personnel by 4.0%, between 2010 and 2014.

North America invented the strategic consultant, but appears not to need many more. Western Europe seems sated, too. Companies are now packed with MBA-holding bosses, many of them former consultants. Well-run companies still know when they need outside expertise, which is why strategy consulting is far from dead. But it is increasingly overshadowed by the less glamorous variety.

Small wonder, then, that the strategy houses are vying for that work. BCG was one of just three big firms to grow (by about 3%) in 2009, and had a good 2010, expanding by some 12%. It is expecting an even better 2012, with 15% growth. (The strategy firms are private partnerships that release few precise figures.) One reason is rapid growth in emerging markets. But BCG, like the other strategy firms, has also made money by grabbing a larger share of "downstream" work.

This is bringing the strategy shops into competition with the biggest players: the Big Four audit firms. These behemoths are buying specialist firms in areas such as technology and health care, thus expanding their size and reach by both specialism and geography. In America they are forbidden from selling consulting to their audit clients. But elsewhere the rules are looser, giving the Big Four a potential "one-stop-shop" offer. Everywhere, they have scale that impresses clients. But those clients are driving harder bargains.

In the past two decades most consulting firms have attached many junior consultants to projects with just a few senior people and partners, moving this army into the clients' offices and billing for as many hours as possible. But increasingly, says Jenny Sutton of the Hong Kong-based RFP Company, clients are refusing to pay for junior staff's on-the-job training. Instead, they are asking for fewer and better consultants and setting them to work alongside their own staff.

In short, consulting is looking less like a licence to print money and more like temporary labour. Clients can bypass the big names and hire consultancies such as Eden McCallum, a British firm that packages teams of experienced independent consultants, or Point B, an American firm that provides only a project manager, letting the client select the team. Big consulting firms (with their big brands) can probably coexist with smaller operators. But midsized firms, which cannot command the same fees and loyalty as the big boys, are feeling the squeeze.

In this, consultants are following a trend that has already hit the law firms whose business model they once copied. Clients want value for money. Consultants whose counsel is useful will still do well. But here's a piece of advice for the rest: in a more competitive market, those who think they can dazzle a client with PowerPoints and bill him by the hour forever will starve. That'll be $1,000, please.

Featured Speakers:

Joseph Kornik

Publisher and Editor-in-Chief,

Consulting magazine

Brian Murphy

Chief of Staff, Point B

Brian Jacobsen

General Manager, Slalom Consulting

Tom Rodenhauser

Managing Director, Advisory Services, Kennedy Consulting Research & Advisory

Sponsor Speaker:

Drew West

Director, Product Marketing,

Deltek

Sponsored By:

Management

Photograph by Peter Hilz/Redux

Management consulting is an enigmatic business. The industry is ridiculed, reviled, or revered, depending on one's perspective. The same attitudes hold true for consulting's standard-bearer: McKinsey & Co., though only the most ill-informed would ridicule a company about which so little is known.

Journalist Duff McDonald's new book The Firm: The Story of McKinsey and its Secret Influence on American Business promises to pull a Toto and reveal McKinsey more as the Kansas medicine man than as the great and powerful Oz of global business.

Founder James McKinsey (and Marvin Bower, who is properly credited for shaping the firm) both fit the bill with their relatively humble Midwestern origins. But despite a plethora of entertaining stories and characters, readers looking for new revelations of what makes McKinsey special will likely come away unsatisfied. Nor will they gain insight into how the 2009 Galleon insider trading scandal that ensnared former McKinsey managing director Rajat Gupta and director Anil Kumar has affected the consulting firm.

Despite McDonald's efforts to demystify McKinsey, the many anecdotes he compiles feel more like a self-actualization exercise: Why choose McKinsey? Because they're the best. Why is McKinsey the best? Because they're McKinsey.

Certainly the firm's history is enlightening for the uninitiated. Chronicling McKinsey's evolution from a 1930s-era, lawyerly-like endeavor of a few dozen people to a multibillion-dollar global juggernaut is interesting but not particularly revelatory.

McDonald correctly points out that McKinsey is not necessarily the best innovator. Competitors such as Boston Consulting Group captured clients' fancy with the simple-to-grasp growth matrix, while Bain introduced the concept of measuring its contribution to clients' value. McKinsey, by comparison, comes across as stodgy and mildly curmudgeonly. Furthermore, the book lauds the firm's many lions, which merely reinforces the dearth of lionesses (and overall diversity) at McKinsey, an oversight that has been rectified only in the last two decades.

One comes away thinking McKinsey's growth is more about willpower masked as intellect. Like a force of nature, McKinsey is deliberate in its formulation. Yet once mobilized, McKinsey simply overwhelms the competition. The book reveals that when clients expressed an expectation that consultants demonstrate their "knowledge," McKinsey created the McKinsey Quarterly-a direct contradiction of Bower's belief that McKinsey consultants should not flout their expertise publicly. (McDonald claims the Quarterly ultimately usurped the Harvard Business Review as showcasing critical thinking on global business issues.)

While McKinsey was founded shortly before World War II, it was Bower who burnished the firm's credentials by helping businesses cope with the unprecedented prosperity brought by post-WWII growth. One could correctly surmise that McKinsey achieved its stature due to the relative naiveté of American business. Modern management consulting owes its existence to Bower and McKinsey's audacity.

McDonald plumbs deeply the limited published material detailing the firm's history-both self-generated by McKinsey, and articles from Bloomberg Businessweek and other business publications. He resurrects some chestnuts that even today make one marvel at McKinsey's influence beyond business (e.g. working for the Eisenhower administration, McKinsey recommended creating the presidential Chief of Staff position). Even former U.S. presidential candidate Mitt Romney-who headed rival Bain & Co.-went on the record saying that as president, he would consider hiring McKinsey to help wring inefficiencies out of the federal bureaucracy. Full disclosure: The author mentions that Bloomberg (which owns Bloomberg Businessweek) hired McKinsey to help Bloomberg chart its future.

Other stories are far less remarkable, though still interesting. James McKinsey's observation when he went from his namesake firm to chief executive officer of Marshall Field at the behest of its board: "Never in my whole life did I know how much more difficult it is to make business decisions myself than merely advising others what to do." The fact that McKinsey is known as a petri dish for CEOs is touched on, with such famous examples as Lou Gerstner (, ) and Michael Jordan (Westinghouse, , Electronic Data Systems). The book also suggests that the best McKinsey people are those who left.

McKinsey partners past and present speak with equal parts bravado and uncertainty. For a firm that is projected by the author to play puppet master to American business, McKinsey's self-reflecting insecurities seem out of place. The firm's collective notion is that the will to succeed eclipses the fear of failure. All McKinsey partners reflexively value the firm over the individual. Even individuals who violated that ethos with their own brand (Tom Peters, Kenichi Ohmae) speak admiringly-or maybe fearfully-of McKinsey's cultural cohesion.

One would have thought that the insider-trading convictions of Gupta and Kumar might inspire some soul searching at McKinsey. Unfortunately, McDonald gives those events almost epilogue-like treatment in the book, a scant 20 pages culled from widespread media coverage. The book's most revealing passage is that McKinsey banished Gupta from the partnership prior to his trial, not for his alleged crime but for violating the firm's ethics.

McDonald's book probes enough of McKinsey's fallibility-disastrous results with Enron and , for example-to satisfy the naysayers. He also likens the firm to a fading empire, where hubris and changing times have diminished the firm's stature.

But like any elite club to which membership is granted exclusively by its members, those who believe in the institution brush aside such critiques. McKinsey's mystique may be an illusion, but the curtain has yet to be pulled back to reveal this Oz.

This was a previously published article that I've since updated and expanded on, to include not only books and magazines but great resources from around the web.

It's important to be well-read when you apply for a consulting job, for several reasons:

1) Your knowledge of current business issues will be tested (directly and indirectly) throughout the recruiting process

2) Gaining exposure to business issues - the situations, problems, solutions, etc - will be a litmus test for your own interest in consulting as a career (if you don't like reading about, for example, how the U.S. automobile industry got into the pickle it's in today and all the areas they need to fix in order to get out, then it may not be a great sign for a future consulting career...unless you hate cars of course :)

3) You get a faster start at the new job and sound smarter from Day One

Consulting-Specific Books The McKinsey Way and The McKinsey Mind, by Ethan Rasiel. Written by a former McKinsey consultant, gives you a great in-depth on firm culture and practices. You'll learn things like 80/20 thinking, hypothesis-driven problem solving, etc - things I will write about in future posts, but here's stuff that's already out there. Plus, the lessons here are equally applicable across any consulting firms.

The McKinsey Way and The McKinsey Mind, by Ethan Rasiel. Written by a former McKinsey consultant, gives you a great in-depth on firm culture and practices. You'll learn things like 80/20 thinking, hypothesis-driven problem solving, etc - things I will write about in future posts, but here's stuff that's already out there. Plus, the lessons here are equally applicable across any consulting firms.

The best part of the books is that they're fast - you can skim them quickly and pretty much extract what you need to know. Even if you aren't applying to McKinsey, you should still read these. They will help you in interviews and in understanding management consulting (and in particular, McKinsey's) culture.

BCG on Strategy - I was recommended this book via the comments below, and had the opportunity to browse through it at a local Barnes & Noble the other day. It's a good read - and very useful for understanding broader strategy frameworks and, to a lesser extent, the evolution of the consulting industry itself in which Boston Consulting Group played a large role (Ever hear the term "cash cow"? Well, BCG invented the growth/share matrix which underpins it :)

General Business-Interest Books Anything by Jim Collins - personal favorites are Good to Great and Built to Last.

Anything by Jim Collins - personal favorites are Good to Great and Built to Last.

Collins does a great job shaping the zeitgeist of current business thinking. Ideas generated from his books are often conversational fodder for consulting teams and influence the way consultants understand their clients and corporations analyze themselves. Phrases like "BHAG" (big hairy audacious goal) are often thrown around in client and team settings, and understanding what it means can go a long way towards making you look good.

The Tipping Point and Outliers by Malcolm Gladwell. He also has a great list of free articles from The New Yorker. I particularly liked "How David Beats Goliath" and "Late Bloomers".

You're not going to learn anything specifically relevant to consulting from Gladwell's books, but his thinking, concepts, and terminology are incredibly popular in business conversations (in particular, his framework in The Tipping Point for understanding how trends spread via archetypes of information-mavens/connectors/salesmen). He's a great writer, and his works are thoroughly enjoyable and relatively fast reads.

Case PrepBeyond The Consulting Bible, which I think is an easily digestible entry to the world of case studies, there are much more comprehensive treatments. Here are the top 2 I've been able to find:

Case In Point, by Marc Cosentino. This is probably the "seminal book" on case studies, if there is one - it's been around a long time, Cosentino is highly respected, and while I did not personally use it during recruiting, I know many people who have and have had generally good results.

Case In Point, by Marc Cosentino. This is probably the "seminal book" on case studies, if there is one - it's been around a long time, Cosentino is highly respected, and while I did not personally use it during recruiting, I know many people who have and have had generally good results.

Pros include a thorough, systematic approach to identifying cases (he has roughly 21 case "types", I believe), and a ton of practice (which is ultimately the most important thing). I believe these case types can be even further distilled into less than 10, but that's the focus of a future post. If you're starting from scratch, this is a great entry point but be prepared to put in the effort and hours to get through it.

How To Get Into The Top Consulting Firms, a Surefire Case Interview Method, by Tim Darling. Heard great things about this from my readers, so I bought it and checked it out. I would definitely recommend it - fast, no-nonsense writing with some very practical tips on how to breakdown and tackle cases.

How To Get Into The Top Consulting Firms, a Surefire Case Interview Method, by Tim Darling. Heard great things about this from my readers, so I bought it and checked it out. I would definitely recommend it - fast, no-nonsense writing with some very practical tips on how to breakdown and tackle cases.

Harvard Business Review. Every issue is worth a quick browse - I haven't read a single one cover-to-cover. But the topics addressed - from how to encourage bottoms-up innovation to establishing the right organizational systems for retaining talented employees - are topics that consultants live and breathe. Reading this will also help you develop your own topical interests within the business world. For example, if you find that you really love innovation and how it's developed within companies, that can be a great topic for cover letters, to bring-up during interviews, etc. Just some extra credit.

Harvard Business Review. Every issue is worth a quick browse - I haven't read a single one cover-to-cover. But the topics addressed - from how to encourage bottoms-up innovation to establishing the right organizational systems for retaining talented employees - are topics that consultants live and breathe. Reading this will also help you develop your own topical interests within the business world. For example, if you find that you really love innovation and how it's developed within companies, that can be a great topic for cover letters, to bring-up during interviews, etc. Just some extra credit.

McKinsey Quarterly. Ditto.

The Economist. Through my McKinsey tenure, I've been surprised by the number of people who regularly read The Economist. It's the one magazine I consistently subscribe to, and will serve you well in understanding the key global issues (and in particular, finance, economics, and business) of the day. Reading The Economist consistently will give you the ability to intelligently discuss current events with recruiters, interviewers, and eventually in the course of your job.

The Economist. Through my McKinsey tenure, I've been surprised by the number of people who regularly read The Economist. It's the one magazine I consistently subscribe to, and will serve you well in understanding the key global issues (and in particular, finance, economics, and business) of the day. Reading The Economist consistently will give you the ability to intelligently discuss current events with recruiters, interviewers, and eventually in the course of your job.

Fortune Magazine. A more personal recommendation - Fortune has consistently high-quality articles and in-depth pieces on leading business thinkers and companies, and is also a much more interesting read than the Economist.

Great WebsitesRecommend via the comments below, Booz & Co's strategy+business website. Similar to The McKinsey Quarterly, lots of great articles on tactics and strategy in the business world.

Consulting Magazine - the industry's most comprehensive resource on consulting news, including everything from personnel shifts at the top firms (for example, McKinsey recently lost a well-known pricing expert) to awards for the industry's top consultants (nominated by their peers).

We offer resume editing and interview prep. Through one-on-one sessions, we'll help you stand out from 1000′s of other applicants and land consulting jobs now!

Tagged as: Built to Last, consulting books, Fortune Magazine, Good to Great, Harvard Business Review, interviews, Jim Collins, recommended reading, Recruiting, The Economist, The McKinsey Mind, The McKinsey Quarterly, The McKinsey Way