DOJ Report on Shooting of Michael Brown

Memorandum ywvutsrponmlihgfedcbaYWVUTSRPONMLJIHGFEDCBA DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE REPORT REGARDING THE CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION INTO THE SHOOTING DEATH OF MICHAEL BROWN BY FERGUSON, MISSOURI POLICE OFFICER DARREN WILSON MARCH 4, 2015

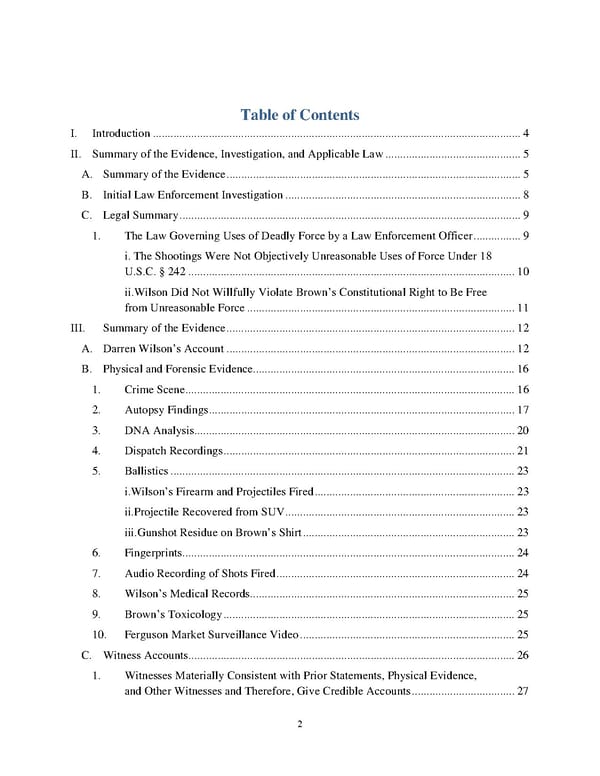

Table of Contents I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 4 II. Summary of the Evidence, Investigation, and Applicable Law .............................................. 5 A. Summary of the Evidence.................................................................................................... 5 B. Initial Law Enforcement Investigation ................................................................................ 8 C. Legal Summary .................................................................................................................... 9 1. The Law Governing Uses of Deadly Force by a Law Enforcement Officer ................ 9 i. The Shootings Were Not Objectively Unreasonable Uses of Force Under 18 U.S.C. § 242 ............................................................................................................... 10 ii.Wilson Did Not Willfully Violate Brown’s Constitutional Right to Be Free from Unreasonable Force ........................................................................................... 11 III. Summary of the Evidence .................................................................................................. 12 A. Darren Wilson’s Account .................................................................................................. 12 B. Physical and Forensic Evidence......................................................................................... 16 1. Crime Scene ................................................................................................................ 16 2. Autopsy Findings ........................................................................................................ 17 3. DNA Analysis............................................................................................................. 20 4. Dispatch Recordings ................................................................................................... 21 5. Ballis tics ..................................................................................................................... 23 i.Wilson’s Firearm and Projectiles Fired .................................................................... 23 ii.Projectile Recovered from SUV.............................................................................. 23 ywvutsrponmlihgfedcbaYWVUTSRPONMLJIHGFEDCBAiii.Gunshot Residue on Brown’s Shirt ........................................................................ 23 6. Fingerprints................................................................................................................. 24 7. Audio Recording of Shots Fired................................................................................. 24 8. Wilson’s Medical Records.......................................................................................... 25 9. Brown’s Toxicology ................................................................................................... 25 10. Ferguson Market Surveillance Video......................................................................... 25 C. Witness Accounts ............................................................................................................... 26 1. Witnesses Materially Consistent with Prior Statements, Physical Evidence, and Other Witnesses and Therefore, Give Credible Accounts ................................... 27 2

i. Witnesses Materially Consistent with Prior Statements, Physical Evidence, and Other Witnesses Who Corroborate That Wilson Acted in SelfDefense ............. 27 ii. Witnesses Consistent with Prior Statements, Physical Evidence, and Other Witnesses Who Inculpate Wilson ............................................................................... 36 2. Witnesses Who Neither Inculpate Nor Fully Corroborate Wilson ............................. 36 3. Witnesses Whose Accounts Do Not Support a Prosecution Due to Materially Inconsistent Prior Statements, or Inconsistencies With the Physical and Forensic Evidence....................................................................................................... 44 IV. Legal Analysis ................................................................................................................... 78 A. Legal Standard ................................................................................................................... 79 B. Uses of Force ..................................................................................................................... 79 1. Shooting at the SUV................................................................................................... 80 2. Wilson’s Subsequent Pursuit of Brown and Shots Allegedly Fired as Brown was Moving Away .................................................................................................... 81 3. Shots Fired After Brown Turned to Face Wilson ...................................................... 82 C. Willfulness ......................................................................................................................... 85 VI. Conclusion ......................................................................................................................... 86 3

I. Introduction At approximately noon on Saturday, August 9, 2014, Officer Darren Wilson of the Ferguson Police Department (“FPD”) shot and killed Michael Brown, an unarmed 18yearold. The Criminal Section of the Department of Justice Civil Rights Division, the United States Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Missouri, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”) (collectively, “The Department”) subsequently opened a criminal investigation into whether the shooting violated federal law. The Department has determined that the evidence does not support charging a violation of federal law. This memorandum details the Department’s investigation, findings, and conclusions. Part I provides an introduction and overview. Part II summarizes the federal investigation and the evidence uncovered during the course of the investigation, and discusses the applicable federal criminal civil rights law and standards of federal prosecution. Part III provides a more indepth summary of the evidence. Finally, Part IV provides a detailed legal analysis of the evidence and explains why the evidence does not support an indictment of Darren Wilson. The Department conducted an extensive investigation into the shooting of Michael Brown. Federal authorities reviewed physical, ballistic, forensic, and crime scene evidence; medical reports and autopsy reports, including an independent autopsy performed by the United States Department of Defense Armed Forces Medical Examiner Service (“AFMES”); Wilson’s personnel records; audio and video recordings; and internet postings. FBI agents, St. Louis County Police Department (“SLCPD”) detectives, and federal prosecutors and prosecutors from the St. Louis County Prosecutor’s Office (“county prosecutors”) worked cooperatively to both independently and jointly interview more than 100 purported eyewitnesses and other individuals claiming to have relevant information. SLCPD detectives conducted an initial canvass of the area on the day of the shooting. FBI agents then independently canvassed more than 300 residences to locate and interview additional witnesses. Federal and local authorities collected cellular phone data, searched social media sites, and tracked down dozens of leads from community members and dedicated law enforcement email addresses and tip lines in an effort to investigate every possible source of information. The principles of federal prosecution, set forth in the United States Attorneys’ Manual (“USAM”), require federal prosecutors to meet two standards in order to seek an indictment. First, we must be convinced that the potential defendant committed a federal crime. See USAM § 927.220 (a federal prosecution should be commenced only when an attorney for the government “believes that the person’s conduct constitutes a federal offense”). Second, we must also conclude that we would be likely to prevail at trial, where we must prove the charges beyond a reasonable doubt. See USAM § 927.220 (a federal prosecution should be commenced only when “the admissible evidence will probably be sufficient to sustain a conviction”); Fed R. Crim P. 29(a)(prosecution must present evidence sufficient to sustain a conviction). Taken 4

together, these standards require the Department to be convinced both that a federal crime 1 occurred and that it can be proven beyond a reasonable doubt at trial. In order to make the proper assessment under these standards, federal prosecutors evaluated physical, forensic, and potential testimonial evidence in the form of witness accounts. As detailed below, the physical and forensic evidence provided federal prosecutors with a benchmark against which to measure the credibility of each witness account, including that of Darren Wilson. We compared individual witness accounts to the physical and forensic evidence, to other credible witness accounts, and to each witness’s own prior statements made throughout the investigations, including the proceedings before the St. Louis County grand jury (“county grand jury”). We worked with federal and local law enforcement officers to interview witnesses, to include reinterviewing certain witnesses in an effort to evaluate inconsistencies in their accounts and to obtain more detailed information. In so doing, we assessed the witnesses’ demeanor, tone, bias, and ability to accurately perceive or recall the events of August 9, 2014. We credited and determined that a jury would appropriately credit those witnesses whose accounts were consistent with the physical evidence and consistent with other credible witness accounts. In the case of witnesses who made multiple statements, we compared those statements to determine whether they were materially consistent with each other and considered the timing and circumstances under which the witnesses gave the statements. We did not credit and determined that a jury appropriately would not credit those witness accounts that were contrary to the physical and forensic evidence, significantly inconsistent with other credible witness accounts, or significantly inconsistent with that witness’s own prior statements. Based on this investigation, the Department has concluded that Darren Wilson’s actions do not constitute prosecutable violations under the applicable federal criminal civil rights statute, 18 U.S.C. § 242, which prohibits uses of deadly force that are “objectively unreasonable,” as defined by the United States Supreme Court. The evidence, when viewed as a whole, does not support the conclusion that Wilson’s uses of deadly force were “objectively unreasonable” under the Supreme Court’s definition. Accordingly, under the governing federal law and relevant standards set forth in the USAM, it is not appropriate to present this matter to a federal grand jury for indictment, and it should therefore be closed without prosecution. II. Summary of the Evidence, Investigation, and Applicable Law A. Summary of the Evidence Within two minutes of Wilson’s initial encounter with Brown on August 9, 2014, FPD officers responded to the scene of the shooting, and subsequently turned the matter over to the SLCPD for investigation. SLCPD detectives immediately began securing and processing the scene and conducting initial witness interviews. The FBI opened a federal criminal civil rights investigation on August 11, 2014. Thereafter, federal and county authorities conducted cooperative, yet independent investigations into the shooting of Michael Brown. 1 The threshold determination that a case meets the standard for indictment rests with the prosecutor, Wayte v. United States, 470 U.S. 598, 607 (1985), and is “one of the most considered decisions a federal prosecutor makes.” USAM 927.200, Annotation. 5

ywvutsrponmlihgfedcbaYWVUTSRPONMLJIHGFEDCBA The encounter between Wilson and Brown took place over an approximately twominute period of time at about noon on August 9, 2014. Wilson was on duty and driving his departmentissued Chevy Tahoe SUV westbound on Canfield Drive in Ferguson, Missouri when 2 he saw Brown and his friend, Witness 101, walking eastbound in the middle of the street. Brown and Witness 101 had just come from Ferguson Market and Liquor (“Ferguson Market”), a nearby convenience store, where, at approximately 11:53 a.m., Brown stole several packages of cigarillos. As captured on the store’s surveillance video, when the store clerk tried to stop Brown, Brown used his physical size to stand over him and forcefully shove him away. As a result, an FPD dispatch call went out over the police radio for a “stealing in progress.” The dispatch recordings and Wilson’s radio transmissions establish that Wilson was aware of the theft and had a description of the suspects as he encountered Brown and Witness 101. As Wilson drove toward Brown and Witness 101, he told the two men to walk on the sidewalk. According to Wilson’s statement to prosecutors and investigators, he suspected that Brown and Witness 101 were involved in the incident at Ferguson Market based on the descriptions he heard on the radio and the cigarillos in Brown’s hands. Wilson then called for backup, stating, “Put me on Canfield with two and send me another car.” Wilson backed up his SUV and parked at an angle, blocking most of both lanes of traffic, and stopping Brown and Witness 101 from walking any further. Wilson attempted to open the driver’s door of the SUV to exit his vehicle, but as he swung it open, the door came into contact with Brown’s body and either rebounded closed or Brown pushed it closed. Wilson and other witnesses stated that Brown then reached into the SUV through the open driver’s window and punched and grabbed Wilson. This is corroborated by bruising on Wilson’s jaw and scratches on his neck, the presence of Brown’s DNA on Wilson’s collar, shirt, and pants, and Wilson’s DNA on Brown’s palm. While there are other individuals who stated that Wilson reached out of the SUV and grabbed Brown by the neck, prosecutors could not credit their accounts because they were inconsistent with physical and forensic evidence, as detailed throughout this report. Wilson told prosecutors and investigators that he responded to Brown reaching into the SUV and punching him by withdrawing his gun because he could not access less lethal weapons while seated inside the SUV. Brown then grabbed the weapon and struggled with Wilson to gain control of it. Wilson fired, striking Brown in the hand. Autopsy results and bullet trajectory, skin from Brown’s palm on the outside of the SUV door as well as Brown’s DNA on the inside of the driver’s door corroborate Wilson’s account that during the struggle, Brown used his right hand to grab and attempt to control Wilson’s gun. According to three autopsies, Brown sustained a close range gunshot wound to the fleshy portion of his right hand at the base of his right thumb. Soot from the muzzle of the gun found embedded in the tissue of this wound coupled with indicia of thermal change from the heat of the muzzle indicate that Brown’s hand was within inches of the muzzle of Wilson’s gun when it was fired. The location of the recovered bullet in the side panel of the driver’s door, just above Wilson’s lap, also corroborates Wilson’s account of the struggle over the gun and when the gun was fired, as do witness accounts that Wilson fired at least one shot from inside the SUV. 2 With the exception of Darren Wilson and Michael Brown, the names of individuals have been redacted as a safeguard against an invasion of their personal privacy. 6

Although no eyewitnesses directly corroborate Wilson’s account of Brown’s attempt to gain control of the gun, there is no credible evidence to disprove Wilson’s account of what occurred inside the SUV. Some witnesses claim that Brown’s arms were never inside the SUV. However, as discussed later in this report, those witness accounts could not be relied upon in a prosecution because credible witness accounts and physical and forensic evidence, i.e. Brown’s DNA inside the SUV and on Wilson’s shirt collar and the bullet trajectory and closerange gunshot wound to Brown’s hand, establish that Brown’s arms and/or torso were inside the SUV. After the initial shooting inside the SUV, the evidence establishes that Brown ran eastbound on Canfield Drive and Wilson chased after him. The autopsy results confirm that Wilson did not shoot Brown in the back as he was running away because there were no entrance wounds to Brown’s back. The autopsy results alone do not indicate the direction Brown was facing when he received two wounds to his right arm, given the mobility of the arm. However, as detailed later in this report, there are no witness accounts that could be relied upon in a prosecution to prove that Wilson shot at Brown as he was running away. Witnesses who say so cannot be relied upon in a prosecution because they have given accounts that are inconsistent with the physical and forensic evidence or are significantly inconsistent with their own prior statements made throughout the investigation. Brown ran at least 180 feet away from the SUV, as verified by the location of bloodstains on the roadway, which DNA analysis confirms was Brown’s blood. Brown then turned around and came back toward Wilson, falling to his death approximately 21.6 feet west of the blood in the roadway. Those witness accounts stating that Brown never moved back toward Wilson could not be relied upon in a prosecution because their accounts cannot be reconciled with the DNA bloodstain evidence and other credible witness accounts. As detailed throughout this report, several witnesses stated that Brown appeared to pose a physical threat to Wilson as he moved toward Wilson. According to these witnesses, who are corroborated by blood evidence in the roadway, as Brown continued to move toward Wilson, Wilson fired at Brown in what appeared to be selfdefense and stopped firing once Brown fell to the ground. Wilson stated that he feared Brown would again assault him because of Brown’s conduct at the SUV and because as Brown moved toward him, Wilson saw Brown reach his right hand under his tshirt into what appeared to be his waistband. There is no evidence upon which prosecutors can rely to disprove Wilson’s stated subjective belief that he feared for his safety. Ballistics analysis indicates that Wilson fired a total of 12 shots, two from the SUV and ten on the roadway. Witness accounts and an audio recording indicate that when Wilson and Brown were on the roadway, Wilson fired three gunshot volleys, pausing in between each one. According to the autopsy results, Wilson shot and hit Brown as few as six or as many as eight times, including the gunshot to Brown’s hand. Brown fell to the ground dead as a result of a gunshot to the apex of his head. With the exception of the first shot to Brown’s hand, all of the shots that struck Brown were fired from a distance of more than two feet. As documented by crime scene photographs, Brown fell to the ground with his left, uninjured hand balled up by his waistband, and his right, injured hand palm up by his side. Witness accounts and cellular phone video prove that Wilson did not touch Brown’s body after he fired the final shot and Brown fell to the ground. 7

Although there are several individuals who have stated that Brown held his hands up in an unambiguous sign of surrender prior to Wilson shooting him dead, their accounts do not support a prosecution of Wilson. As detailed throughout this report, some of those accounts are inaccurate because they are inconsistent with the physical and forensic evidence; some of those accounts are materially inconsistent with that witness’s own prior statements with no explanation, credible for otherwise, as to why those accounts changed over time. Certain other witnesses who originally stated Brown had his hands up in surrender recanted their original accounts, admitting that they did not witness the shooting or parts of it, despite what they initially reported either to federal or local law enforcement or to the media. Prosecutors did not rely on those accounts when making a prosecutive decision. ywvutsrponmlihgfedcbaYWVUTSRPONMLJIHGFEDCBAWhile credible witnesses gave varying accounts of exactly what Brown was doing with his hands as he moved toward Wilson – i.e., balling them, holding them out, or pulling up his pants up – and varying accounts of how he was moving – i.e., “charging,” moving in “slow motion,” or “running” – they all establish that Brown was moving toward Wilson when Wilson shot him. Although some witnesses state that Brown held his hands up at shoulder level with his palms facing outward for a brief moment, these same witnesses describe Brown then dropping his hands and “charging” at Wilson. B. Initial Law Enforcement Investigation Wilson shot Brown at about 12:02 p.m. on August 9, 2014. Within minutes, FPD officers responded to the scene, as they were already en route from Wilson’s initial radio call for assistance. Also within minutes, residents began pouring onto the street. At 12:08 p.m., FPD officers requested assistance from nearby SLCPD precincts. By 12:14 p.m., some members of the growing crowd became increasingly hostile in response to chants of “[We] need to kill these motherfuckers,” referring to the police officers on scene. At around the same time, about 12:15 p.m., Witness 147, an FPD sergeant, informed the FPD Chief that there had been a fatal officer involved shooting. At about 12:23 p.m., after speaking with one of his captains, the FPD Chief contacted the SLCPD Chief and turned over the homicide investigation to the SLCPD. Within twenty minutes of Brown’s death, paramedics covered Brown’s body with several white sheets. The SLCPD Division of Criminal Investigation, Bureau of Crimes Against Persons (“CAP”) was notified at 12:43 p.m. to report to the crime scene to begin a homicide investigation. When they received notification, SLCPD CAP detectives were investigating an armed, masked hostage situation in the hospice wing at St. Anthony’s Medical Center in the south part of St. Louis County, nearly 37 minutes from Canfield Drive. They arrived at Canfield Drive at approximately 1:30 p.m. During that time frame, between about 12:45 p.m. and 1:17 p.m., SLCPD reported gunfire in the area, putting both civilians and officers in danger. As a result, canine officers and additional patrol officers responded to assist with crowd control. SLCPD expanded the perimeter of the crime scene to move the crowd away from Brown’s body in an effort to preserve the crime scene for processing. Upon their arrival, SLCPD detectives from the Bureau of Criminal Identification Crime Scene Unit erected orange privacy screens around Brown’s body, and CAP detectives alerted the 8

St. Louis County Medical Examiner (“SCLME”) to respond to the scene. To further protect the integrity of the crime scene, and in accordance with common police practice, SLCPD personnel did not permit family members and concerned neighbors into the crime scene (with one brief exception). Also in accordance with common police practice, crime scene detectives processed the crime scene with Brown’s body present. According to SLCPD CAP detectives, they have one opportunity to thoroughly investigate a crime scene before it is forever changed upon the removal of the decedent’s body. Processing a homicide scene with the decedent’s body present allows detectives, for example, to accurately measure distances, precisely document body position, and note injury and other markings relative to other aspects of the crime scene that photographs may not capture. In this case, crime scene detectives had to stop processing the scene as a result of two more reports of what sounded like automatic weapons gunfire in the area at 1:55 p.m. and 2:11 p.m., as well as some individuals in the crowd encroaching on the crime scene and chanting, “Kill the Police,” as documented by cell phone video. At each of those times, having exhausted their existing resources, SLCPD personnel called emergency codes for additional patrol officers from throughout St. Louis County in increments of twentyfive. Livery drivers sent to transport Brown’s body upon completion of processing arrived at 2:20 p.m. Their customary practice is to wait on scene until the body is ready for transport. However, an SLCPD sergeant briefly stopped them from getting out of their vehicle until the gunfire abated and it was safe for them to do so. The SLCME medicolegal investigator arrived at 2:30 p.m. and began conducting his investigation when it was reasonably safe to do so. Detectives were at the crime scene for approximately five and a half hours, and throughout that time, SLCPD personnel continued to seek additional assistance, calling in the Highway Safety Unit at 2:38 p.m. and the Tactical Operations Unit at 2:44 p.m. Witnesses and detectives described the scene as volatile, causing concern for both their personal safety and the integrity of the crime scene. Crime scene detectives and the SLCME medicolegal investigator completed the processing of Brown’s body at approximately 4:00 p.m, at which time Brown’s body was transported to the Office of the SLCME. C. Legal Summary 1. The Law Governing Uses of Deadly Force by a Law Enforcement Officer The federal criminal statute that enforces Constitutional limits on uses of force by law enforcement officers is 18 U.S.C. § 242, which provides in relevant part, as follows: Whoever, under color of any law, . . . willfully subjects any person . . . to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States [shall be guilty of a crime]. To prove a violation of Section 242, the government must prove the following elements beyond a reasonable doubt: (1) that the defendant was acting under color of law, (2) that he deprived a victim of a right protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States, (3) that he acted willfully, and (4) that the deprivation resulted in bodily injury and/or death. There is no dispute that Wilson, who was on duty and working as a patrol officer for the FPD, acted under 9

yxwvutsrponmlkjihgfedcbaWVUTSRPONMLIHGFEDCBA color of law when he shot Brown, or that the shots resulted in Brown’s death. The determination of whether criminal prosecution is appropriate rests on whether there is sufficient evidence to establish that any of the shots fired by Wilson were unreasonable, as defined under federal law, given the facts known to Wilson at the time, and if so, whether Wilson fired the shots with the requisite “willful” criminal intent. i. The Shootings Were Not Objectively Unreasonable Uses of Force Under 18 U.S.C. § 242 In this case, the Constitutional right at issue is the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition against unreasonable seizures, which encompasses the right of an arrestee to be free from “objectively unreasonable” force. Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386, 39697 (1989). “The ‘reasonableness’ of a particular use of force must be judged from the perspective of a reasonable officer on the scene, rather than with the 20/20 vision of hindsight.” Id. at 396. “Careful attention” must be paid “to the facts and circumstances of each particular case, including the severity of the crime at issue, whether the suspect poses an immediate threat to the safety of the officers or others, and whether he is actively resisting arrest or attempting to evade arrest by flight.” Id. Allowance must be made for the fact that law enforcement officials are often forced to make splitsecond judgments in circumstances that are tense, uncertain, and rapidly evolving. Id. at 39697. The use of deadly force is justified when the officer has “probable cause to believe that the suspect pose[s] a threat of serious physical harm, either to the officer or to others.” Tennessee v. Garner, 471 U.S. 1, 11 (1985); see Nelson v. County of Wright, 162 F.3d 986, 990 (8th Cir. 1998); O’Bert v. Vargo, 331 F.3d 29, 36 (2d Cir. 2003) (same as Garner); Deluna v. City of Rockford, 447 F.3d 1008, 1010 (7th Cir. 2006), citing Scott v. Edinburg, 346 F.3d 752, 756 (7th Cir. 2003) (deadly force can be reasonably employed where an officer believes that the suspect’s actions place him, or others in the immediate vicinity, in imminent danger of death or serious bodily injury). As detailed throughout this report, the evidence does not establish that the shots fired by Wilson were objectively unreasonable under federal law. The physical evidence establishes that Wilson shot Brown once in the hand, at close range, while Wilson sat in his police SUV, struggling with Brown for control of Wilson’s gun. Wilson then shot Brown several more times from a distance of at least two feet after Brown ran away from Wilson and then turned and faced him. There are no witness accounts that federal prosecutors, and likewise a jury, would credit to support the conclusion that Wilson fired at Brown from behind. With the exception of the two wounds to Brown’s right arm, which indicate neither bullet trajectory nor the direction in which Brown was moving when he was struck, the medical examiners’ reports are in agreement that the entry wounds from the latter gunshots were to the front of Brown’s body, establishing that Brown was facing Wilson when these shots were fired. This includes the fatal shot to the top of Brown’s head. The physical evidence also establishes that Brown moved forward toward Wilson after he turned around to face him. The physical evidence is corroborated by multiple eyewitnesses. Applying the wellestablished controlling legal authority, including binding precedent from the United States Supreme Court and Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals, the evidence does 10

not establish that it was unreasonable for Wilson to perceive Brown as a threat while Brown was punching and grabbing him in the SUV and attempting to take his gun. Thereafter, when Brown started to flee, Wilson was aware that Brown had attempted to take his gun and suspected that Brown might have been part of a theft a few minutes before. Under the law, it was not unreasonable for Wilson to perceive that Brown posed a threat of serious physical harm, either to him or to others. When Brown turned around and moved toward Wilson, the applicable law and evidence do not support finding that Wilson was unreasonable in his fear that Brown would once again attempt to harm him and gain control of his gun. There are no credible witness accounts that state that Brown was clearly attempting to surrender when Wilson shot him. As detailed throughout this report, those witnesses who say so have given accounts that could not be relied upon in a prosecution because they are irreconcilable with the physical evidence, inconsistent with the credible accounts of other eyewitnesses, inconsistent with the witness’s own prior statements, or in some instances, because the witnesses have acknowledged that their initial accounts were untrue. ii. Wilson Did Not Willfully Violate Brown’s Constitutional Right to Be Free from Unreasonable Force Federal law requires that the government must also prove that the officer acted willfully, that is, “for the specific purpose of violating the law.” Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91, 101107 (1945) (discussing willfulness element of 18 U.S.C. § 242). The Supreme Court has held that an act is done willfully if it was “committed” either “in open defiance or in reckless disregard of a constitutional requirement which has been made specific or definite.” Screws, 325 U.S. at 105. The government need not show that the defendant knew a federal statute or law protected the right with which he intended to interfere. Id. at 10607 (“[t]he fact that the defendants may not have been thinking in constitutional terms is not material where their aim was not to enforce local law but to deprive a citizen of a right and that right was protected”); United States v. Walsh, 194 F.3d 37, 5253 (2d Cir. 1999) (holding that jury did not have to find defendant knew of the particular Constitutional provision at issue but that it had to find intent to invade interest protected by Constitution). However, we must prove that the defendant intended to engage in the conduct that violated the Constitution and that he did so knowing that it was a wrongful act. Id. “[A]ll the attendant circumstances” should be considered in determining whether an act was done willfully. Screws, 325 U.S. at 107. Evidence regarding the egregiousness of the conduct, its character and duration, the weapons employed and the provocation, if any, is therefore relevant to this inquiry. Id. Willfulness may be inferred from blatantly wrongful conduct. See id. at 106; see also United States v. Reese, 2 F.3d 870, 881 (9th Cir. 1993) (“Intentionally wrongful conduct, because it contravenes a right definitely established in law, evidences a reckless disregard for that right; such reckless disregard, in turn, is the legal equivalent of willfulness.”); United States v. Dise, 763 F.2d 586, 592 (3d Cir. 1985) (holding that when defendant “invades personal liberty of another, knowing that invasion is violation of state law, [defendant] has demonstrated bad faith and reckless disregard for [federal] constitutional rights”). Mistake, fear, misperception, or even poor judgment does not constitute willful conduct prosecutable under the statute. See United States v. McClean, 528 F.2d 1250, 1255 (2d Cir. 1976) (inadvertence or mistake negates willfulness for purposes of 18 U.S.C. § 242). 11

As detailed below, Wilson has stated his intent in shooting Brown was in response to a perceived deadly threat. The only possible basis for prosecuting Wilson under 18 U.S.C. § 242 would therefore be if the government could prove that his account is not true – i.e., that Brown never punched and grabbed Wilson at the SUV, never attempted to gain control of Wilson’s gun, and thereafter clearly surrendered in a way that no reasonable officer could have failed to perceive. There is no credible evidence to refute Wilson’s stated subjective belief that he was acting in selfdefense. As discussed throughout this report, Wilson’s account is corroborated by physical evidence and his perception of a threat posed by Brown is corroborated by other credible eyewitness accounts. Even if Wilson was mistaken in his interpretation of Brown’s conduct, the fact that others interpreted that conduct the same way as Wilson precludes a determination that he acted for the purpose of violating the law. III. Summary of the Evidence As detailed below, Darren Wilson has stated that he shot Michael Brown in response to a perceived deadly threat. This section begins with Wilson’s account because the evidence that follows, in the form of forensic and physical evidence and witness accounts, must disprove his account beyond a reasonable doubt in order for the government to prosecute Wilson. A. Darren Wilson’s Account Darren Wilson made five voluntary statements following the shooting. Wilson’s first statement was to Witness 147, his supervising sergeant at the FPD, who responded to Canfield 3 Drive within minutes and immediately spoke to Wilson. Wilson’s second statement was made to an SLCPD detective about 90 minutes later, after Wilson returned to the FPD. This interview continued at a local hospital while Wilson was receiving medical treatment. Third, SLCPD detectives conducted a more thorough interview the following morning, on August 10, 2014. Fourth, federal prosecutors and FBI agents interviewed Wilson on August 22, 2014. Wilson’s attorney was present for both interviews with the SLCPD detectives. Two attorneys were present for his interview with federal agents and prosecutors. Wilson’s fifth statement occurred when he appeared before the county grand jury for approximately 90 minutes on September 16, 2014. According to Wilson, he was traveling westbound on Canfield Drive, having just finished another call, when he saw Brown and Witness 101 walking single file in the middle of the street on the yellow line. Wilson had never before met either Brown or Witness 101. Wilson approached Witness 101 first and told him to use the sidewalk because there had been cars trying to pass them. When pressed by federal prosecutors, Wilson denied using profane language, explaining that he was on his way to meet his fiancée for lunch, and did not want to antagonize the two subjects. Witness 101 responded to Wilson that he was almost to his destination, and Wilson replied, “What’s wrong with the sidewalk?” Wilson stated that Brown unexpectedly 3 Witness 147 was jointly interviewed by SLCPD detectives and federal agents and prosecutors on August 19, 2014. He then testified before the county grand jury on September 16, 2014. Witness 147 never documented what Wilson told him during those initial few minutes after the shooting. Witness 147 acknowledged that while talking to Wilson, he was also focused on the shooting scene and crowd safety. 12

responded, “Fuck what you have to say.” As Wilson drove past Brown, he saw cigarillos in Brown’s hand, which alerted him to a radio dispatch of a “stealing in progress” that he heard a few minutes prior while finishing his last call. Wilson then checked his rearview mirror, and realized that Witness 101 matched the description of the other subject on the radio dispatch. Wilson requested assistance over the radio, stating that he had two subjects on Canfield Drive. Wilson explained that he intended to stop Brown and Witness 101 and wait for backup before he did any further investigation into the theft. Wilson reversed his vehicle and parked in a manner to block Brown and Witness 101 from walking any further. Upon doing so, he attempted to open his driver’s door, and said, “Hey, come here.” Before Wilson got his leg out, Brown 4 responded, “What the fuck are you gonna do?” Brown then slammed the door shut and Wilson told him to “get back.” Wilson attempted to open the door again. Wilson told the county grand jury that he then told Brown, “Get the fuck back,” but Brown did not comply and, using his body, pushed the door closed on Wilson. Brown placed his hands on the window frame of the driver’s door, and again Wilson told Brown to “get back.” To Wilson’s surprise, Brown then leaned into the driver’s window, so that his arms and upper torso were inside the SUV. Brown started assaulting Wilson, “swinging wildly.” Brown, still with cigarillos in his hand, turned around and handed the items to Witness 101 using his left hand, telling Witness 101 “take these.” Wilson used the opportunity to grab Brown’s right arm, but Brown used his left hand to twice punch Wilson’s jaw. As Brown assaulted Wilson, Wilson leaned back, blocking the blows with his forearms. Brown hit Wilson on the side of his face and grabbed his shirt, hands, and arms. Wilson feared that Brown’s blows could potentially render him unconscious, leaving him vulnerable to additional harm. Wilson explained that he resorted to his training and the “use of force triangle” to determine how to properly defend himself. Wilson explained that he did not carry a taser, and therefore, his options were mace, his flashlight, his retractable asp baton, and his firearm. Wilson’s mace was on his left hip and Wilson explained that he knew that the space within the SUV was too small to use it without incapacitating himself in the process. Wilson’s asp baton was located on the back of his duty belt. Wilson determined that not only would he have to lean forward to reach it, giving more of an advantage to Brown, but there was not enough space in the SUV to expand the baton. Wilson’s flashlight was in his duty bag on the passenger seat, out of his reach. Wilson explained that his gun, located on his right hip, was his only readily accessible option. Consequently, while the assault was in progress and Brown was leaning in through the window with his arms, torso, and head inside the SUV, Wilson withdrew his gun and pointed it at Brown. Wilson warned Brown to stop or he was going to shoot him. Brown stated, “You are 4 The Ferguson Market store clerk’s daughter stated that Brown used a similar statement when her father tried to stop Brown from stealing cigarillos, i.e., “What you gonna do?” While it might seem odd that a person in Brown’s position would verbally confront a police officer, the fact that another witness at a separate location described Brown as speaking similarly a few minutes earlier tends to corroborate Wilson. 13

5 6 too much of a pussy to shoot,” and put his right hand over Wilson’s right hand, gaining control of the gun. Brown then maneuvered the gun so that it was pointed down at Wilson’s left hip. Wilson explained that Brown’s size and strength, coupled with his standing position outside the SUV relative to Wilson’s seated position inside the SUV, rendered Wilson completely vulnerable. Wilson stated that he feared Brown was going to shoot him because Brown had control of the gun. Wilson managed to use his left elbow to brace against the seat, gaining enough leverage to push the gun forward until it lined up with the driver’s door, just under the handle. Wilson explained that he twice pulled the trigger but the gun did not fire, most likely because Brown’s hand was preventing the gun from functioning properly. Wilson pulled the trigger a third time and the gun fired into the door. Immediately, glass shattered because the window had been down, and Wilson noticed blood on his own hand. Wilson initially thought he had been cut by the glass. Brown appeared to be momentarily startled because he briefly backed up. Wilson saw Brown put his hand down to his right hip, and initially assumed the bullet went through the door and struck Brown there. Wilson then described Brown becoming enraged, and that Brown “looked like a demon.” Brown then leaned into the driver’s window so that his head and arms were inside the SUV and he assaulted Wilson again. Wilson explained that while blocking his face with his left hand, he tried to fire his gun with his right hand, but the gun jammed. Wilson lifted the gun, without looking, and used both hands to manually clear the gun while also trying to shield himself. He then successfully fired another shot, holding the gun in his right hand. According to Wilson, he could not see where he shot, but did not think that he struck Brown because he saw “smoke” outside the window, seemingly from the ground, indicating to him a point of impact that was farther away. Brown then took off running. Wilson radioed for additional assistance, calling out that shots were fired. Wilson then chased after Brown on foot. Federal prosecutors questioned Wilson as to why he did not drive away or wait for backup, but instead chose to pursue Brown despite the attack he just described. Wilson explained that he ran after Brown because Brown posed a danger to others, having just assaulted a police officer and likely stolen from Ferguson Market. Given Brown’s violent and otherwise erratic behavior, Wilson was concerned that Brown was a danger to anyone who crossed his path as he ran. Wilson denied firing any shots while Brown was running from him. Rather he kept his gun out, but down in a “low ready” position. Wilson explained that he chased after Brown, repeatedly yelling at him to stop and get on the ground. Brown kept running, but when he was about 20 to 30 feet from Wilson, abruptly stopped, and turned around toward Wilson, appearing “psychotic,” “hostile,” and “crazy,” as though he was “looking through” Wilson. While making 5 According to Wilson’s sergeant, Witness 147, Wilson told him that Brown made that comment later when Brown was charging at Wilson in the roadway. Witness 147 remembered this part of Wilson’s account when he testified before the county grand jury, and not when he was interviewed by state and federal authorities. In every other account, Wilson stated that Brown made that comment as soon as he withdrew his gun. 6 During his second interview with SLCPD detectives, Wilson stated he was unsure with which hand Brown reached for Wilson’s gun. During all other statements, when asked, Wilson said that Brown used his right hand. 14

a “grunting noise” and with what Wilson described as the “most intense aggressive face” that he ywvutsrponmlihgfedcbaYWVUTSRPONMLJIHGFEDCBA had ever seen on a person, Brown then made a hoplike movement, similar to what a person does when he starts running. Brown then started running at Wilson, closing the distance between them to about 15 feet. Wilson explained that he again feared for his life, and backed up as Brown came toward him, repeatedly ordering Brown to stop and get on the ground. Brown failed to comply and kept coming at Wilson. Wilson explained that he knew if Brown reached him, he “would be done.” During Brown’s initial strides, Brown put his right hand in what appeared to be his waistband, albeit covered by his shirt. Wilson thought Brown might be reaching for a weapon. Wilson fired multiple shots. Brown paused. Wilson explained that he then paused, again yelled for Brown to get on the ground, and again Brown charged at him, hand in waistband. Wilson backed up and fired again. The same thing happened a third time where Brown very briefly paused, and Wilson paused and yelled for Brown to get on the ground. Brown continued to “charge.” Wilson described having tunnel vision on Brown’s right arm, all the while backing up as Brown approached, not understanding why Brown had yet to stop. Wilson fired the last volley of shots when Brown was about eight to ten feet from him. When Wilson fired the last shot, he saw the bullet go into Brown’s head, and Brown “went down right there.” Wilson initially estimated that on the roadway, he fired five shots and then two shots, none of which had any effect on Brown. Then Brown leaned forward as though he was getting ready to “tackle” Wilson, and Wilson fired the last shot. Federal prosecutors questioned Wilson about his actions after the shooting. Wilson explained that he never touched Brown’s body. Using the microphone on his shoulder, Wilson radioed, “Send me every car we got and a supervisor.” Within seconds, additional officers and his sergeant arrived on scene. In response to specific questions by federal prosecutors, Wilson explained that he had left his keys in the ignition of his vehicle and the engine running during the pursuit, so he went back to his SUV to secure it. In so doing, he was careful only to touch the door and the keys. Wilson then walked over to his sergeant, Witness 147, and told him what 7 happened. Both Wilson and Witness 147 explained that Witness 147 told Wilson to wait in his SUV, but Wilson refused, explaining that if he waited there, it would be known to the neighborhood that he was the shooter. Wilson explained that the atmosphere was quickly becoming hostile, and he either needed to be put to work with his fellow officers or he needed to leave. Per Witness 147’s orders, Wilson drove Witness 147’s vehicle to the FPD. It was during the drive that Wilson realized he was not bleeding, but had what he thought was Brown’s blood on both hands. As soon as Wilson got to the police department, he scrubbed both hands. When federal prosecutors challenged why he did so in light of the potential evidentiary value, Wilson explained that he realized after the fact that he should not have done so, but at the time he was reacting to a potential biohazard while still under the stress of the moment. Wilson then rendered his gun safe and packaged it with the one remaining round in an evidence envelope. When federal prosecutors further questioned why he packaged his own gun, Wilson explained that he wanted to ensure its preservation for analysis because it would prove what happened. At first, he hoped Brown’s fingerprints or epithelial DNA from sweat on his hand might be present from when Brown grabbed the gun. But then Wilson actually saw blood on the gun, and 7 According to Witness 147, he spoke to Wilson while Wilson was seated in his SUV. 15

assumed that since he was not bleeding, the blood likely belonged to Brown, and therefore, Brown’s DNA would be present. During Wilson’s interview with federal authorities, prosecutors and agents focused on whether he was consistent with his previous statements, the motivation for his actions, and his training and experience relative to when the use of deadly force is appropriate. Federal prosecutors challenged Wilson with specificity about why he stopped Brown and whether he was aware that Brown and Witness 101 were suspects in the Ferguson Market robbery. Similarly, prosecutors challenged Wilson about his decision to use deadly force inside the SUV, to chase after Brown, and to again use deadly force on Brown in the roadway. Wilson responded to those challenges in a credible manner, offering reasonable explanations to the questions posed. ywvutsrponmlihgfedcbaYWVUTSRPONMLJIHGFEDCBA At the time of his interview, federal prosecutors and agents were aware of the autopsy, DNA, and ballistics results, as detailed below. Wilson’s account was consistent with those results, and consistent with the accounts of other independent eyewitnesses, whose accounts were also consistent with the physical evidence. Wilson’s statements were consistent with each other in all material ways, and would not be subject to effective impeachment for inconsistencies 8 or deviation from the physical evidence. Therefore, in analyzing all of the evidence, federal prosecutors found Wilson’s account to be credible. B. Physical and Forensic Evidence 1. Crime Scene As noted above, SLCPD detectives from the Bureau of Criminal Identification, Crime Scene Unit processed the scene of the shootings. During processing, they photographed and took video of the crime scene, including Brown’s body and Wilson’s SUV. They measured distances from Brown’s body, Wilson’s SUV, and various pieces of evidence. As described in detail 9 below, they recovered twelve spent shell casings. One was located on the ground between the driver’s door and back passenger door of the SUV and another was located near the sidewalk, diagonally across from the driver’s door. Seven casings and one spent projectile were located in the general vicinity of Brown’s body. Those casings were located on the ground next to the left side of his body (on the south side of Canfield Drive), with four closer to his body, and three in the grassy area of the sidewalk. The projectile was located on the right side of Brown’s body (on the north side of Canfield Drive). Three additional casings were further east, or further away from where Brown came to rest. Crime scene detectives also recovered a spent projectile fragment from the wall of an apartment building located east of Brown’s body, in the direction 8 Federal prosecutors were aware of and reviewed prior complaints against Wilson, as well as media reports, alleging Wilson engaged in misconduct. Such allegations were not substantiated, and do not contain information admissible in federal court in support of a prosecution. 9 The locations of the shell casings are consistent with Wilson’s account and the credible witness accounts. However, shell casings provide limited evidentiary value relative to the precise location of the shooter and bullet trajectory because they tend to bounce and roll unpredictably after being ejected from the firearm and before coming to rest. 16

10 toward which Wilson had been shooting. As described below, crime scene detectives noted 11 apparent blood in the roadway approximately 17 feet and 22 feet east of where Brown’s body was found and east of the casings that were recovered, consistent with Brown moving toward Wilson before his death. There was no other blood found in the roadway, other than the pool of blood surrounding Brown’s body. Crime scene detectives recovered Brown’s St. Louis Cardinals baseball cap by the driver’s door of the SUV. Two bracelets, one black and yellow, and the other beaded, were 12 found on either side of the SUV. Brown’s Nike flip flops were located in the roadway, the left one near the front of the driver’s side of the vehicle, approximately 126 feet west of where Brown’s head came to rest, and the right one in the center of the roadway, 82.5 feet west of where Brown’s head came to rest and just south of the center line. This is consistent with witness descriptions that Brown, wearing his socks, described as bright yellow with a marijuana leaf pattern, ran diagonally away from the SUV, crossing over the center line. Prior to transport of Brown’s body, the SLCME medicolegal investigator documented the position of Brown’s body on the ground. Brown was on his stomach with his right cheek on the ground, his buttocks partially in the air. His uninjured left arm was back and partially bent under his body with his left hand at his waistband, balled up in a fist. His injured right arm was back behind him, almost at his right side, with his injured right hand at hip level, palm up. Brown’s shorts were midway down his buttocks, as though they had partially fallen down. The forensic analysis of the seized evidence is detailed below: 2. Autopsy Findings There were three autopsies conducted on Michael Brown’s body. SLCME conducted the first autopsy. A private forensic pathologist conducted the second autopsy at the request of Brown’s family. AFMES conducted the third autopsy at the Department’s request. The SLCME, AFMES, and the private forensic pathologist were consistent in their findings unless otherwise noted. Brown was shot at least six and at most eight times. As described below, two entrance wounds may have been reentry wounds, accounting for why the number of shots that struck Brown is not definite. Of the eight gunshot wounds, two wounds, a penetrating gunshot wound to the apex of Brown’s head, and a graze or tangential wound to the base of Brown’s right thumb, have the most significant evidentiary value when determining the prosecutive merit of this matter. The former is significant because the gunshot to the head would have almost immediately 10 Crime scene detectives also noted a hole in the wall of an apartment building located on the south side of Canfield Drive, east of Wilson’s SUV. They removed a small section of siding, but were unable to determine whether there was a projectile within the wall without causing significant structural damage to the building. There is no evidence to indicate what caused the hole or when it was made. 11 As noted below, the blood in the roadway was determined to be Brown’s blood. 12 It was never determined to whom these bracelets belong or when they were left in the street. 17

incapacitated and immobilized Brown; the latter is significant because it is consistent with Brown’s hand being in close range or having nearcontact with the muzzle of Wilson’s gun and corroborates Wilson’s account that Brown struggled with him to gain control of the gun in the SUV. The skin tags, or flaps of skin created by the graze of the bullet associated with the right thumb wound, indicate bullet trajectory. They were oriented toward the tip of the right thumb, indicating the path of the bullet went from the tip of the thumb toward the base. Microscopic analysis of the wound indicates that Brown’s hand was near the muzzle of the gun when Wilson pulled the trigger. Both AFMES and SLCME pathologists observed numerous deposits of dark particulate foreign debris, consistent with gunpowder soot from the muzzle of the gun embedded in and around the wound. The private forensic pathologist called it gunshot residue, opining that Brown’s right hand was less than a foot from the gun. The SLCME pathologist opined that the muzzle of the gun was likely six to nine inches from Brown’s hand when it fired. AFMES pathologists opined that the particulate matter was, in fact, soot and was found at the exact point of entry of the wound. The soot, along with the thermal change in the skin resulting from heat discharge of the firearm, indicates that the base of Brown’s right hand was within inches of the muzzle of Wilson’s gun when it fired. AFMES pathologists further opined that, given the tangential nature of the wound, the fact that the soot was concentrated on one side of the wound, and the bullet trajectory as detailed below, the wound to the thumb is consistent with Brown’s hand being on the barrel of the gun itself, though not the muzzle, at the time the shot was fired. The presence of soot also proves that the wound to the thumb was the result of the 13 gunshot at the SUV. As detailed below, several witnesses described Brown at or in Wilson’s SUV when the first shot was fired, and a bullet was recovered from within the driver’s door of the SUV. There is no evidence that Wilson was within inches of Brown’s thumb other than in the SUV at the outset of the incident. Additionally, according to the SLCME pathologist and the private forensic pathologist, a piece of Brown’s skin recovered from the exterior of the driver’s door of the SUV is consistent with skin from the part of Brown’s thumb that was wounded. It is therefore a virtual certainty that the first shot fired was the one that caused the tangential thumb wound. The order of the remaining shots cannot be determined, though the shot to Brown’s head would have killed him where he stood, preventing him from making any additional purposeful 14 movement toward Wilson after the final shots were fired. The fatal bullet entered the skull, the brain, and the base of the skull, and came to rest in the soft tissues of the right face. The trajectory of the bullet was downward, forward, and to the right. Brown could not have been standing straight when Wilson fired this bullet because Wilson is slightly shorter than Brown. Brown was likely bent at the waist or falling forward when he received this wound. It is also possible, although not consistent with credible eyewitness accounts, that Brown had fallen to his knees with his head forward when Wilson fired this shot. However, the lack of stippling and soot indicates that Wilson was at least two to three feet from Brown when he fired. 13 Soot typically appears if the muzzle is within less than one foot of the target and stippling typically appears if the muzzle is within two to three feet of the target. 14 This fact was critical for prosecutors in evaluating the credibility of witness accounts that stated that Brown continued moving toward Wilson after Wilson ceased firing shots. 18

The remaining gunshots, like the thumb wound, were all on Brown’s right side and none of them would have necessarily immediately immobilized Brown. The lack of soot and stippling indicates that the shots were fired from a distance of at least two to three feet. However, as described below, because of environmental conditions and because Brown’s shirt was blood soaked, it was not suitable for gunshot residue analysis to determine muzzletotarget distance. Therefore, we cannot reliably say whether gunshot residue on Brown’s shirt might have provided evidence of muzzletotarget distance. Regardless, gunshot residue is inherently delicate and 15 easily transferrable. ywvutsrponmlihgfedcbaYWVUTSRPONMLJIHGFEDCBA In addition to the thumb wound and the fatal shot to the head, Brown sustained a gunshot wound to his central forehead, with a corresponding exit wound of the right jaw. The bullet tracked through the right eye and right orbital bone, causing fractures of the facial bones. Brown sustained another gunshot wound to the upper right chest, near the neck. The bullet tracked though the right clavicle and upper lobe of the right lung, and came to rest in the right chest. Brown sustained another entrance wound to his lateral right chest. The bullet tracked through and fractured the eighth right rib, puncturing the lower lobe of the right lung. The bullet was recovered from the soft tissue of the right back. The AFMES pathologists and the private forensic pathologist opined that the right chest wound could have been a reentry wound from an arm wound as described below, and the clavicle wound could have been a reentry wound from the bullet that entered Brown’s forehead and exited his jaw. The SLCME pathologist also allowed for the possibility of reentry wounds, but did not opine with specificity due to the variability of such wounds. Brown also sustained a gunshot wound to the front of the upper right arm, near the armpit, with a corresponding gunshot exit wound of the back of the upper right arm. The remaining gunshot wounds were also to the right arm. These bullet trajectories are described according to the standard anatomic diagram, that is, standing, arms at sides, palms facing forward. That said, Brown sustained a gunshot wound to the dorsal (back) right forearm, below the elbow. The bullet tracked through the bone in the forearm, fracturing it, and exiting through the ventral (front) right forearm. Finally, Brown sustained a tangential or graze gunshot wound to the right bicep, above the elbow. Given the mobility of the arm, it is impossible to determine the position of the body relative to the shooter at the time the arm wounds were inflicted. Therefore, the autopsy results do not indicate whether Brown was facing Wilson or had his back to him. They do not indicate whether Brown sustained those two arm wounds while his hands were up, down, or by his waistband. The private forensic pathologist opined that he would expect a reentry wound across Brown’s stomach if Brown’s hand was at his waistband at the time Wilson fired. However, as mentioned, there is no way to know the exact position of Brown’s arm relative to his waistband 15 Although Brown’s shirt was blood soaked, the private forensic pathologist noted the following with regard to Brown’s shorts and socks, “Examination of the clothing…shows small dried blood drops on his khaki shorts and yellow socks most consistent with drops from the hand wound.” This was significant to prosecutors because it is not inconsistent with Brown lowering his hands and/or putting his hand(s) near his waistband. 19

at the time the bullets struck. Therefore, these gunshot wounds neither corroborate nor discredit Wilson’s account or the account of any other witness. However, the concentration of bullet wounds on Brown’s right side is consistent with Wilson’s description that he focused on Brown’s right arm while shooting. 16 The autopsy established that Brown did not sustain gunshot wounds to his back. There was no evidence to corroborate that Wilson choked, strangled, or tightly grasped Brown on or around his neck, as described by Witness 101 in the summary of his account below. There were no bruises, abrasions, hemorrhaging of soft tissues, or any other injuries to the neck, nor was there evidence of petechial hemorrhaging of Brown’s remaining left eye. The private forensic pathologist opined that although the lack of injury does not signify the absence of strangulation, it would be “surprising,” given Brown’s size, if Wilson attempted to strangle Brown. The private forensic pathologist explained that the act of strangling is often committed by the stronger person, as it is rarely effective if attempted by the person of smaller size or weaker 17 strength. Brown sustained a one inch superficial incised wound to the right middle of the front of his left arm. SCLME differed with AFMES, characterizing this wound as an abrasion, but AFMES opined that this was more like a cut, consistent with being caused by broken window glass. Brown also sustained abrasions to the right side of the head and face, including abrasions near the right forehead, the lateral right face, and the upper right cheek, consistent with Brown falling and impacting the ground with his face. The private forensic pathologist opined that the severity of these abrasions could have been caused by involuntary seizures as Brown died. He also opined, as did the SLCME pathologist, that these abrasions were consistent with Brown impacting the ground upon death and sliding on the roadway due to the momentum from quickly moving forward. According to the AFMES and SCLME pathologists, Brown also had small knuckle abrasions, but the pathologists could not link them to any specific source. The SLCME pathologist opined they may have been inflicted post mortem, while the AFMES pathologist 18 opined that they were too small to determine whether they were caused pre or postmortem. ywvutsrponmlihgfedcbaYWVUTSRPONMLJIHGFEDCBA The private forensic pathologist did not note any knuckle abrasions or injury to Brown’s hands, explaining that he would expect Brown to have knuckle injury if Wilson sustained broken bones, but not necessarily bruising. AFMES pathologists likewise concurred that lack of injury to Brown’s hands is not inconsistent with bruising to Wilson’s face. 3. DNA Analysis 16 This evidence was significant to prosecutors when determining the credibility of those witness accounts that stated that Wilson shot Brown in the back. 17 This evidence was significant to prosecutors when determining the credibility of those witness accounts that stated that Wilson choked or grabbed Brown by the neck at the outset of the struggle at the SUV. 18 Post mortem abrasions are consistent with Brown’s hands hitting the ground after the final shot to the vortex of the head. It is less likely that they were inflicted during removal of Brown’s body because Brown’s hands were secured in brown paper bags prior to transport. 20

The SLCPD Crime Laboratory conducted DNA analysis on swabs taken from Wilson, Brown, Wilson’s gun, and the crime scene. Brown’s DNA was found at four significant locations: on Wilson’s gun; on the roadway further away from where he died; on the SUV driver’s door and inside the driver’s cabin area of the SUV; and on Wilson’s clothes. A DNA mixture from which Wilson’s DNA could not be excluded was found on Brown’s left palm. Analysis of DNA on Wilson’s gun revealed a major mixture profile that is 2.1 octillion times more likely a mixture of DNA from Wilson and DNA from Brown than from Wilson and 19 anyone else. This is conclusive evidence that Brown’s DNA was on Wilson’s gun. Brown is the source of the DNA found in two bloodstains on Canfield Drive, approximately 17 and 22 feet east of where Brown fell to his death, proving that Brown moved forward toward Wilson prior to the fatal shot to his head. Brown’s DNA was found both on the inside and outside of the driver’s side of the SUV. Brown is the source of DNA in blood found on the exterior of the passenger door of the driver’s side of the SUV. Likewise, a piece of Brown’s skin was recovered from the exterior of the driver’s door of the SUV, consistent with Brown sustaining injury while at that door. Brown is also the source of the major contributor of a DNA mixture found on the interior driver’s door handle of the SUV. A DNA mixture obtained from the top of the exterior of the driver’s door revealed a major mixture profile that is 6.9 million times more likely a mixture of DNA from Wilson and DNA from Brown than from Wilson and anyone else. Brown’s DNA was found on Wilson’s uniform shirt collar and pants. With respect to the left side of Wilson’s shirt and collar, it is 2.1 trillion times more likely that the recovered DNA mixture is DNA from Wilson and DNA from Brown than from Wilson and anyone else. Similarly, with respect to a DNA mixture obtained from the left side of Wilson’s pants, it is 34 sextillion times more likely that the mixture is DNA from Wilson and DNA from Brown than from Wilson and anyone else. Brown is also the source of the major male profile found in a DNA mixture found in a bloodstain on the upper left thigh of Wilson’s pants. DNA analysis of Brown’s left palm revealed a DNA mixture with Brown as the major contributor, and Wilson being 98 times more likely the minor contributor than anyone else. DNA analysis of Brown’s clothes, right hand, fingernails, and clothes excluded Wilson as a possible contributor. 4. Dispatch Recordings 19 While it is possible that Wilson inadvertently transferred Brown’s blood from his own hand to his gun either after the struggle or while packaging his gun (even though Wilson claimed to have already washed his hands), such a possibility is speculative. The autopsy results and bullet trajectory are consistent with Brown’s DNA being present on the gun as a result of the struggle over the gun. Regardless, the absence of Brown’s DNA on Wilson’s gun would not change the prosecutive decision. 21

According to FPD records, at about 11:53 a.m., a dispatcher called out a “stealing in progress” at the address of Ferguson Market while Wilson was in the midst of a sick infant call. During his interview with federal officials, Wilson told prosecutors and agents that he heard the call on his portable radio, but did not hear the specifics about the location of the “stealing in progress.” He also stated that he heard that one of the suspects was wearing a “black shirt,” that they had stolen cigarillos, and were going toward the QuickTrip. The actual description given was that of a “black male in a white tshirt,” “running toward the QuickTrip,” and that “he took a whole box of Swisher cigars.” Two officers, Witness 145 and Witness 146, the same two FPD officers who first responded to Canfield Drive after the shooting, responded to the Ferguson Market. At approximately 11:56 a.m., Witness 145, via radio, added, “He’s with another male. He’s got a red Cardinals hat, white tshirt, yellow socks, and khaki shorts.” Wilson left the sick call at approximately 11:58 a.m., after EMS arrived to transport the mother and sick child to the hospital. Twentyseven seconds later, Wilson radioed to Witness 145 and Witness 146, “Do you guys need me?,” corroborating that Wilson was aware of the theft at Ferguson Market prior to his encounter with Brown. Witness 145 responded that the suspect “disappeared into the woodwork.” Wilson, having not heard him, asked the dispatcher to “relay.” The dispatcher then clarified, “He thinks that they…disappeared.” Wilson then said “clear,” indicating that he understood. Wilson drove his police SUV west on Canfield Drive, where he encountered Brown and Witness 101 walking east in the middle of the street. Wilson’s last recorded radio transmission occurred at approximately noon when he called out, “Put me on Canfield with two and send me another car,” consistent with Wilson’s account that he radioed for backup once he interacted with Brown and Witness 101. Several radio transmissions followed from dispatch and from Officer 145 seeking a response from Wilson to no avail. About one minute and forty seconds following Wilson’s last transmission, Witness 145 called out to send the supervising sergeant to Canfield Drive and Copper Creek Court, the location of the shooting incident. There were no recorded radio transmissions from Wilson from the time Wilson called for assistance to the time that Witness 145 called for a supervisor. As noted above, Wilson stated that he also radioed for backup after the initial shots when Brown ran from the SUV, and then again after he shot Brown to death. According to Wilson, as he left the shooting scene, he realized that his radio must have switched from channel 1, which he had been using, to channel 3 during the initial struggle. Channel 3 is a dedicated channel for the North County Fire Department. It only receives transmissions, and therefore, officers cannot use that channel to transmit messages to dispatch. While this is not definitive evidence that Wilson attempted to call for assistance both after the initial shots in the SUV and after he killed Brown, it offers a plausible explanation for the lack of radio transmissions. Moreover, as detailed below, there are several witnesses who state that Wilson paused in the SUV after Brown took off running, arguably giving him enough time to attempt to radio dispatch. Likewise, several witnesses saw Wilson appear to use his shoulder microphone after Brown fell to the ground, presumably to radio dispatch. 22

5. Ballistics Witness 143, a firearms and toolmarks examiner with the SLCPD, conducted the ballistics analysis for the St. Louis County Police Laboratory. Witness 144, an FBI firearms and toolmarks examiner, conducted gunshot residue analysis and reconstructed the shooting incident. i. Wilson’s Firearm and Projectiles Fired There were a total of five projectiles, and a fragment from another projectile, recovered from the crime scene and Brown’s autopsy. There were a total of 12 shell casings recovered from the crime scene. Wilson’s gun can hold up to 13 rounds, 12 in the magazine and one in the chamber. Witness 143 testfired Wilson’s Sig Sauer S&W .40 caliber semiautomatic pistol, noting apparent blood on the gun. He compared the test bullets and casings to those seized as evidence from Brown’s body and the crime scene. Witness 143 confirmed that all 12 shell casings were fired from Wilson’s gun, consistent with the one round remaining in the gun after the shooting. Witness 143 also confirmed that four of the recovered projectiles, as well as the recovered fragment, were fired from Wilson’s gun. The remaining projectile, recovered from the inside of the driver’s door of Wilson’s SUV, was too damaged to conclusively find that it came from Wilson’s gun. ii. Projectile Recovered from SUV Witness 144 conducted a shooting incident reconstruction of the interior driver’s door panel of Wilson’s SUV to determine the trajectory of the bullet that was recovered there. The trajectory of the bullet was at a downward angle from left to right, striking the armrest near the interior door handle, entering the door from inside the SUV, and coming to rest inside the door. This is consistent with Wilson’s description of the initial gunshot. Witness 144 conducted gunshot residue analysis on the inside of the driver’s door. Particulate and vaporous lead residues found on the interior driver’s door panel near the interior window weather stripping and on the interior side frame of the driver’s door were, like the recovery of the bullet itself, consistent with the discharge of a firearm. These residues were unsuitable for muzzletotarget distance determinations. However, vaporous lead residues rarely are deposited at a distance greater than 24 inches, consistent with Wilson discharging his firearm while seated in the driver’s seat, less than two feet from the driver’s door. iii. Gunshot Residue on Brown’s Shirt Witness 144 conducted gunshot residue analysis on Brown’s shirt. For the most part, gunshot residue analysis can only determine whether defects in an item, i.e., the holes in his shirt, are the result of gunshots. Analysis cannot determine the directional travel of bullets. Witness 144 examined seven holes in the shirt. Gunshot residues in the form of nitrite and bullet wipe lead residues were found near some of the holes. This does not necessarily suggest that the remaining holes were not created by bullets. According to Witness 144, lack of 23

gunshot residue could be due to the possibility of intervening conditions, like large amounts of blood, environmental conditions, or the way the shirt was folded and packaged. Likewise, the presence of nitrite residues tells very little. Nitrite residues were found near three holes in Brown’s right sleeve, and one hole in the right chest of this shirt. Testfiring of the gun showed that nitrite residues appear at a muzzletotarget distance of eight feet or less, consistent with Wilson’s description and several other witness descriptions that Wilson and Brown were about eight feet apart during the final shots. However, the residues were not in a measurable pattern. This means that they may not even be associated with the specific holes in the shirt that they are near, but rather may be just indiscriminate residue from any of the shots, including the close range shots at the SUV, or transferred from one shot to another during the handling and packaging of the clothes. 6. Fingerprints Wilson’s gun was not tested for the presence of Brown’s fingerprints. After SLCPD crime scene detectives recovered Wilson’s gun, they submitted the gun for DNA analysis rather than for fingerprints analysis. The detectives told federal prosecutors that they knew that typically testing for one would preclude testing for the other, and there was a high likelihood of DNA given the presence of apparent blood on the gun. They also knew that even according to Wilson, Brown never had sole possession of the gun, and if Brown ever had control of the gun at all, it was only when Brown’s hand was over Wilson’s hand during a struggle for the gun, lessening the likelihood of fingerprints. Furthermore, based on their training and experience, there was a greater likelihood of finding a DNA profile on the gun than lifting fingerprints with 20 enough fine ridge detail to make it suitable for comparison. Because the gun was swabbed in 21 its entirety, it could not later undergo latent fingerprint analysis. SLCPD crime scene detectives lifted five latent fingerprints from the outside of the driver’s door of the SUV. Two were unsuitable for comparison; one was determined to be Wilson’s fingerprint; and the remaining two prints, although suitable for comparison, belonged to neither Brown nor Wilson. The leather interior of the SUV was unsuitable for recovering latent prints. Fingerprint examiners also tested Wilson’s duty belt for fingerprints, but none recovered was suitable for comparison. 7. Audio Recording of Shots Fired Witness 136 was in his apartment using a video chat application on his mobile phone when the shooting occurred. According to Witness 136, he heard “maybe three” gunshots followed by a five to six second pause. After those first gunshots, Witness 136 recorded the remainder of his chat and turned it over to the FBI. The recording is about 12 seconds long and captured a total of 10 gunshots. The gunshots begin after the first four seconds. The recording 20 The grips and hammer, the latter of which was where blood was recovered on Wilson’s gun, are textured, making it difficult to lift latent prints. 21 Fingerprint analysis would not have changed the prosecutive decision. Had the gun yielded Brown’s fingerprints, such evidence would further corroborate Wilson’s account. If the gun did not test positive for Brown’s fingerprints, the state of the evidence would remain the same. 24