StartUp Tools: Market Research Tools

.jpg)

Frost & Sullivan, founded in 1961, has more than 40 global offices with more than 1,800 industry consultants, market research analysts, technology analysts and economists. We are a growth partnership company focused on helping our clients achieve transformational growth as they work through an economic environment dominated by accelerating change, increasing risk and the powerful disruptive impact of the conversion of new business models, disruptive technologies and mega trends on their industry.

We are the world leader in growth consulting and the integrated areas of technology research, market research, mega trends, economic research, best practices, training, customer research, competitive intelligence, and corporate strategy.

Research

Monitoring and analyzing technical, economic, mega trends, competitive, customer, best practices and emerging markets research into one system which supports the entire "growth cycle" enables our clients to have a complete picture of their industry, as well as how all other industries are impacted by these factors.

Our proprietary 360° research provides our clients critical information that aids in development of the visionary skills necessary to develop a growth pipeline that meets or exceeds the company's growth targets.

Consulting

Growth Consulting services encompass customized research, business strategy, and organizational development initiatives. Growth Consulting provides uniquely powerful and practical solutions to help companies successfully address their growth challenges. These services are tailor-made.

Clients leverage our unique combination of market expertise, global presence, and relationships with key industry players to help them with a specific business decision or broader issues or challenges.

Events & Training

Our global events and training programs are focused on helping companies transform their organization through best practices and experiential learning. Our totally unique events are engineered to maximize interactivity, collaboration and networking in an environment that sparks innovation.

Our corporate training & development programs are interactive workshops aimed at maximizing change through experiential learning. We find that executives get the most value when they can learn by doing.

This site uses cookies. Cookies are used to track visitors to Frost.com so we can better understand which portions of our site best serve you. This data will be used for the following purposes: Completion and support of the current activity and Web site and system administration. This data will be used only by Frost & Sullivan.

Your Portal for Petroleum Statistics and Information

API is the premier source for petroleum industry data and information. API's data and statistics are accurate, comprehensive, timely, and quoted widely. For pricing and ordering information, please contact our primary distributor, Information Handling Services, at 1-800-854-7179 or visit the API-IHS Storefront for more information. Key statistical reports include the following:

reports total U.S. and regional data relating to refinery operations and the production of the five major petroleum products: oxygenated, reformulated, and other finished motor gasoline, naphtha, and kerosene jet fuel, distillate (by sulphur content) and residual fuel oil. These products represent more than 80% of total refinery production. Inventories of these products as well as crude oil and unfinished oils are also included, along with refinery input data.

Published weekly every Tuesday afternoon (published Wednesday afternoon in the event of a Monday holiday). Click here for the complete 2014 schedule.

If you are interested in purchasing the WSB early release (4:30 pm EST each Tuesday), please contact Lakshmy Mahon at [email protected].

the most reliable source for historical data on energy, reserves, exploration and drilling, production, finance, prices, demand, refining, imports, exports, offshore transportation, natural gas and the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

Published twice per year in February and August.

The imports report contains monthly data on the imports of crude oil and petroleum products by PADD. Details include importer, port of entry, country of origin, recipient, destination, quantity, API gravity and sulphur content (for crude oil and residual fuel oil).

The exports report contains monthly data on volumes of crude oil and petroleum product exports. Also included are data by place of exit and by destination.

Published in the second week of each month.

presents data on the inventory levels of ethane, propane, isobutane, normal butane and pentanes plus. These inventories, located at natural gas plants, refineries, bulk terminals and in underground storage, are grouped into eight regional areas.

Published in the final days of each month.

contains timely interpretation and analysis of recent developments for major products, production, imports, refinery operations, and inventories - accompanied by API's estimates of these data for the most recent month and graphs of major series, including product deliveries, crude oil production, imports, refinery activity, and inventories for the past 24 months.

The December issue, published in early January, presents year-end supply/demand estimates and summarizes developments of the year. Quarterly estimates are included four times per year. (See 2014 MSR schedule)

The QWCR provides detailed information on reported drilling activity and estimates the total number of wells and footage drilled. The estimates of quarterly completions and footage are displayed by well type, well class, and quarter for the ten years prior. More detailed estimates of quarterly completions and footage are disaggregated by well type, depth interval, and quarter for the current year and two years prior. In addition, wells reported to API (not estimates) are listed on a state and regional level, disaggregated by well class, well type, and quarter, for the current year and two years prior.

Published in the first week following the end of the quarter.

Contact: Franziska Economy at [email protected].

The JAS is an annual survey that contains the only long-term source of information of detailed U.S. drilling expenditures on wells, footage, and related expenditures in the United States. An Analysis & Trends section provides detailed information and graphs about offshore and onshore wells, shale wells, coalbed methane wells, and sidetrack wells. The data presented in the U.S. Summary Tables section are broken down by well type (oil wells, gas wells, and dry holes) and by depth interval. Additionally, the data in these tables are disaggregated by well class (exploratory wells and development wells) and offshore and onshore production. A few regional and state tables are also available in this report.

Prior year's survey is published in December of the current year.

Contact: Franziska Economy at [email protected].

is an annual sales of propane, butane, ethane, and pentanes plus; it is the only source of data of annual propane sales on a state level. Propane data are categorized by state and type of use, i.e., residential, commercial, sales to retail dispensers, internal-combustion engine fuel, industrial, agricultural, and chemical. It is published in cooperation with the Gas Processors Association, National Propane Gas Association, and the Propane Education & Research Council.

Prior year's survey is published in December of the current year.

Industry-Wide Surveys

Industry-wide surveys are described briefly below. If you know you are interested in a specific survey listed below, click on the title and you can obtain a copy of any free report or contact and ordering information for other reports.

Environmental Expenditures Survey (1990-2012)

Contact: Adebukola Adefemi at [email protected].

Workplace Injuries and Illnesses Safety (WIIS) Report 2003-2012

Contact: Adebukola Adefemi at [email protected].

Process Safety Performance Measurement Report

Contact: Adebukola Adefemi at [email protected].

Oil Spills in U.S. Navigable Waters (1997-2006)

Contact: Adebukola Adefemi at [email protected]

Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Contact: Adebukola Adefemi at [email protected]

Pipeline Performance Tracking System (PPTS)

This is an effort by the Pipeline segment to collect very detailed information about every pipeline incident since 1999. The Statistical Services group created a client-based software that is dynamically linked to API through the Internet to collect the data. The Statistical Services group maintains the software and handles technical support for the effort. Contact Hazem Arafa at [email protected].

Survey on Petroleum Industry Occupational Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities (OII)

The OII is an annual survey that collects data on Petroleum Industry Occupational Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities, both within the United States and internationally, as well as for both employees and contract workers. The Survey on Petroleum Industry Occupational Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities: Report to Participants is available only to participating companies and is available through the OII database website. The Aggregate Data Only version of the report, however, is available to the public. The last five annual reports are available below.

Prior year's survey is published in March of the current year.

Contact: Franziska Economy at [email protected].

The Survey on Petroleum Industry Occupational Injuries, Illnesses and Fatalities (OII) is conducted annually. Participation is voluntary and the number of participating companies varies from year to year. Below find the last 5 years of reports.

2005 Survey on Petroleum Industry Occupational Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities Summary Report: Aggregate Data Only

2006 Survey on Petroleum Industry Occupational Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities Summary Report: Aggregate Data Only

2007 Survey on Petroleum Industry Occupational Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities Summary Report: Aggregate Data Only

2008 Survey on Petroleum Industry Occupational Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities Summary Report: Aggregate Data Only

2009 Survey on Petroleum Industry Occupational Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities Summary Report: Aggregate Data Only

Electronic Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions calculator tool for the petroleum and natural gas industry

API Newsroom Update (October 17, 2014):

Petroleum Demand Falls in September and Third Quarter (includes Monthly Statistical Report)Petroleum Facts at a Glance

Monthly Statistical Report

Monthly Import Statistics for July 2014 (latest available)

Disclaimer: All data is based on information that has been voluntarily reported to API by petroleum companies operating in the U.S. API does not guarantee the accuracy of the data and disclaims any liability in connection with its use.

Rights of Information: All information offered in the statistical reports and surveys offered in this subscription service are the sole and exclusive property of API, its subcontractors, and other information providers who may, from time to time, supply information to API. You agree that, unless specific permission is granted in writing, you will not publish, broadcast, retransmit, store, reproduce, modify, upload, post, distribute in any way or resell such information or in any way violate the copyright of any provider of information to API. You may use this information solely within your company. This information may not be distributed or otherwise transferred outside your company without the express consent of the API. Reproduction for internal use only is permitted, provided that copies are made without modification and with all copyrighted notices preserved.

Since his first full day in office, President Obama has prioritized making government more open and accountable and has taken substantial steps to increase citizen participation, collaboration, and transparency in government.

Data.gov, the central site for U.S. Government data, is an important part of the Administration's overall effort to open government.

Open Data in the United States

A large number of cities, counties, and states have open data sites.

Download the full list of Open Data Sites in the following formats: [ CSV] | [ EXCEL]

A number of local governments in the United States have launched their own sites with access to machine-readable data.

U.S. States

U.S. Cities and Counties

Open Data Internationally

Nations around the world have followed the example of Data.gov in opening up a wide variety of data for citizens and businesses. Download the full list of open data sites in the following formats: [ CSV] | [ EXCEL]

Open Source

Data.gov was built with open source software, CKAN, and WordPress. Anyone, especially local, state, and foreign governments are welcome to borrow the code behind Data.gov.

Healthcare.gov

As the first website to be demonstrated by a sitting President of the United States, Healthcare.gov already occupies an unusual place in history. In October, it will take on an even more important historic role, guiding millions of Americans through the process of choosing health insurance.

How a website is built or designed may seem mundane to many people, but when the site in question is focused upon such an important function, what it looks like and how it works matter. Last week, the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) relaunched Healthcare.gov with a new appearance and modern technology that is unusual in federal-government websites.

"It's fast, built in static HTML, completely scalable and secure," said Bryan Sivak, chief technology officer of HHS, in an interview. "It's basically setting up a web server. That's the beauty of it." What makes such an ambitious experiment in social coding more unusual is that the larger political and health-care policy context that it's being been built within is more fraught with tension and scrutiny than any other arena in the federal government.

The implementation and outcomes of the Affordable Care Act -- AKA "Obamacare" -- will affect millions of people, from the premiums they pay to the incentives for the health care they receive. "The goal is get people enrolled," said Sivak. "A step to that goal is to build a health insurance marketplace. It is so much better to build it in a way that's open, transparent and enables updates. This is better than a big block of proprietary code locked up in a CMS [content management system]."

-thumb-570x335-125914.jpg)

Healthcare.gov

Thinking differently about a .gov

The new site has been built in public for months, iteratively created on Github using cutting edge open-source technologies. Healthcare.gov is the rarest of birds: a next-generation website that also happens to be a .gov.

"We needed to evolve from the previous site but didn't want a total departure," said Ed Mullen, a user experience designer who has worked on Healthcare.gov since it was first launched, in an interview. "The web has changed dramatically in that time. Part of adapting to that [change] has been creating a site that really understands consumers. Today, consumers are doing all kinds of things across the web. We're comparing ourselves to Rdio and similar services. We want to be aligned with the current thinking of the Web."

The people that helped to build the new Healthcare.gov are unusual: Instead of some obscure sub-contractor in a nameless office park in northern Virginia, the site was iteratively created by a cross-disciplinary team of developers and editors at HHS, and contractors at Teal Design, Edward Mullen Studio, and Development Seed, a scrappy startup in a garage in the District of Columbia.

"This is such a lean site," said Jon Booth, head of the web and new media group at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), in an interview. "HHS had a blanket contract when we when awarded this. Aquilent got creative and brought people on with powerful skills, like Ed and Jessica, a designer at Teal Media, and Development Seed. Most of my team is working on this site; we have internal UX, information architects, designers, developers, and infrastructure people that stood up the cloud environment. Their collaboration is one of the high points of this process."

The involvement of Development Seed drove specific technology choices that led to substantial improvements in design and function. The startup first made its mark in the DC tech scene consulting on Drupal, an open source content management system that has become popular in the federal government over the past several years. Recently, Development Seed has been pushing the limits of lightweight Web design, open data-driven maps and open-source code.

"This is our ultimate dogfooding experience," said Eric Gundersen, the co-founder of Development Seed, in an interview. "We're going to build it and then buy insurance through it."

"The work that they're doing is amazing," said Sivak, "like how they organize their sprints and code. It's incredible what can happen when you give a team of talented developers and managers and let them go."

The new Healthcare.gov will fill a yawning gap in the technology infrastructure deployed to support the mammoth law, providing a federal choice engine for the more than 30 different states that did not develop their own health-insurance exchanges, but the site is just one component of the insurance exchanges. Others may not be ready by the October deadline. According to a recent report from the Government Accountability Office, the Department of Health and Human Services' (HHS) Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is behind in implementing key aspects of the law, such as training the workers who will help people navigate the process, certifying the plans that will be sold on the exchanges, and determining the eligibility of consumers for federal subsidies. Despite all this, HHS expressed confidence to the GAO that exchanges will be open and functioning in every state on October 1.

On that day, Healthcare.gov will be the primary interface for Americans to learn about and shop for health insurance, as Dave Cole, a lead developer at Development Seed, wrote in a blog post this March. Cole, who served as a senior advisor to the United States chief information officer and deputy director of new media at the White House, was a key part of the team that moved WhiteHouse.gov to Drupal. As he explained, the code will be open in two important ways:

First, Bryan [Sivak] pledged, "everything we do will be published on GitHub," meaning the entire code-base will be available for reuse. This is incredibly valuable because some states will set up their own state-based health insurance marketplaces. They can easily check out and build upon the work being done at the federal level. GitHub is the new standard for sharing and collaborating on all sorts of projects, from city geographic data and laws to home renovation projects and even wedding planning, as well as traditional software projects.

Moreover, all content will be available through a JSON API, for even simpler reusability. Other government or private sector websites will be able to use the API to embed content from healthcare.gov. As official content gets updated on healthcare.gov, the updates will reflect through the API on all other websites. The White House has taken the lead in defining clear best practices for web APIs.

Putting open source to work

According to Sivak, his team didn't get directly involved in the new Healthcare.gov until November 2012.

After that, "we facilitated the right conversations around what to build and how to build it, emphasizing the consumer-facing aspects of it," he said. "The other part was to figure what the right infrastructure was going to be to build this thing."

That decision is where this story gets especially interesting, if you're interested in how government uses technology to deliver information to the people it serves.

Government websites have not, historically, been sterling examples of design or usability. Unfortunately, in many cases, they're also built at great expense, given the dependence of government agencies on contractors and systems integrators, and use technologies that are years behind the rest of the web.

Healthcare.gov could have gone in the same direction, but for the influence of its young chief technology officer, an "entrepreneur-in-residence" who had successfully navigated the bureaucracies of the District of Columbia and state of Maryland. "Our first plan was to leverage Percussion, a commercial CMS that we'd been using for a long time," said Sivak. "The problem I had with that plan was that it wasn't going to be easy to update the code. The process was complicated. Simple changes to navigation were going to take a month."

At that point, Sivak did what most people do in this new millennium when making a technology choice: He reached out to his social networks and went online. "We started talking to people about a better way, including people who had just come off the Obama campaign," he said. "I learned about the ground they had broken for the political space, from A/B testing to lightweight infrastructure, and started reading about where all that came from. We started thinking about Jekyll as a platform and using Prose.io."

After Sivak and his team read about Development Seed's work with Jekyll, they contacted the startup directly. After a little convincing, Development Seed agreed to consult on one more .gov project.

"A Presidential Innovation Fellow used same tech we're using for several of their projects," said Cole. "Bryan [Sivak] heard about it and talked to us. He asked where we would go. We wanted to be on Github. We knew there were performance and reliability benefits from building the stack on HTML."

Jekyll, for those who are unfamiliar with web-development trends, is a way for developers to build a static website from dynamic components. Instead of running a traditional website with a relational database and server-side code, using Jekyll enables programmers to create content like they create code. The end result of this approach is a site that loads faster for users, a crucial performance issue, particularly on mobile devices. "Instead of [running] farms of application servers to handle massive load, you're basically slimming down to two," said Sivak. "You're just using HTML5, CSS, and Javascript, all being done in responsive design. The way it's being built matters. You could in theory do the same with application servers and a CMS, but it would be much more complex. What we're doing here is giving anyone with basic skills to basic changes on the fly. You don't need expensive consultants."

That adds up to cost savings. Sites that are heavily trafficked -- as Healthcare.gov can reasonably expected to be - normally have to use a caching layer to serve static content and add more server capacity as demand increases.

"When we worked with the World Bank, they chose a plan from Rackspace for 16 servers," said Gundersen. "That added tens of thousands of dollars, with a huge hosting bill every month."

HHS had similar strategic plans for the new site, at least at first. "They were planning 32 servers, between staging, production and disaster recovery, with application servers for different environments," said Cole. "You're just talking about content. There just needs to be one server. We're going to have two, with one for backup. That's a deduction of 30 servers."

Why was Development Seed able to succeed in selling this approach to coding and collaboration with a federal agency and other contractors, in contrast to traditional systems integrators? Or to put it another way, what could a mapping startup teach the world about making government work better? Quite a lot, as it turns out.

"It helps that we're running a cloud SaaS business," said Cole, referring to MapBox. "If you're not doing your own products and using your own products, you're not going to have a sense of what the future is. You can put Wordpress into Amazon but then you'll have problems; it wasn't designed to be a cloud application. In this case, the code is completely cloud-ready and able to be scaled through a CDN [content delivery network], through Akamai. Understanding that comes from running a cloud company."

While Jekyll eliminates the need for a full-blown content management system for Healthcare.gov (and with it, related costs) people managing the site still need to be able to update it. That's where Prose.io comes in.

Prose.io is an open-source content editor developed by Development Seed that gives non-programmers a clean user interface to update pages. "If you create content and run Jekyll, it requires content editors to know code," said Cole. "Prose is the next piece. You can run it on your on own servers or use a hosted version. It gives access to content in a CMS-like interface, basically adding a WYSIWYG [What You See Is What You Get] skin, giving you a text editor in the browser."

To non-technical users, Prose.io looks much like the standard "What you see is what you get" interface, familiar from Wordpress or Microsoft Word, with a couple bells and whistles, such as mobile editing.

"You can basically preview in live," said Cole. "You usually don't get a full in-browser preview. The difference is you have this with no backend CMS. It's just a directory and text files, with a web interface that exposes it. There are no servers, no infrastructure, and no monthly costs. All you need is a need free web app and Github. If you don't want to use that, use Git and Github Enterprise."

Prose was built by Development Seed to enable them to pass management of code off to the owners of websites. That's exactly how it's being used here.

"We were doing Jekyll sites and wanted to turn them over to clients who could then maintain them themselves," said Cole. "It's just a wrapper around the workflow, with design aesthetic to make it clean and something in the backend that's technical."

The technology behind Healthcare.gov also delivered on a crucial feature: a version geared toward a growing Spanish-speaking population that is quite likely to access the site on a mobile device.

"When you look at providing a Spanish translation or a mobile site, it becomes really complicated trying to have a site render in different ways, in different configurations," said Cole. "A CMS needs a different version for each one. That's not true here, with a responsive, easy-to-iterate upon design. A change is a quick process, not altering any application code."

The HHS tech team is now singing the praise of that choice.

"One of the strong attractions for working in Jekyll is that you can have multiple versions of everything," said Booth. "We can provide the exact same experience and mobile capacity on the Spanish website as on the English version."

While the front end of Healthcare.gov is distributed over Akamai, the back end of the site will be be hosted in a secure cloud.

"The servers are hosted in Terramark, a cloud computing firm that's a subsidiary of Verizon," said Booth. "When we got involved, Terramark had already been selected as the vendor. We inherited that; it was our first major cloud deployment. It's wonderful, compared to the traditional 'buy a lot of boxes and get the servers set up.' Percussion was fine as a CMS but the scalability issue was huge for us, really overarching."

Combining these two approaches finally realized some of the more aspirational rhetoric about the potential of "cloud computing" to deliver better savings and services that has bounced around Washington over the past four years.

"For us, it's a combination of Terramark as data center and Akamai as content distribution network," said Cole. "For the relaunch, no consumer traffic hits Terramark at all, with the exception of search queries. We have completely pushed the website out to Akamai, which gives us a lot of flexibility. This is by far the fastest site we've ever built. We wanted to make sure that this site is not adding any overhead, is as lightweight as it can be."

Embracing citizen-centric design

"Thinking differently" about this site went beyond technical choices for architecture or how rules and regulations were instantiated in code. If you visit Healthcare.gov on a smartphone or tablet, you'll notice how quickly it loads, how clean the design is on mobile, and how the site renders to fit the size of your screen.

That's no accident, as Mullen and Booth explained.

"Across the board, there was agreement that it needed to be all about the consumer," said Mullen. "That was the mantra from the beginning. It comes down to understanding the audience, from thinking about the reading level of all content to writing clear, declarative sentences."

Focusing on the consumer -- or the citizen -- as the primary driver for design and technical decisions may sound like common sense but it's not a principle that appears to have animated the construction of many .gov websites over the past two decades. In recent years, however, design principles are redefining how online government is created and delivered, with notable results.

"We knew, building this marketplace from scratch, that we needed to have consistency," said Mullen. "We had to make sure all efforts work together, from outreach, engagement, education, to enrollment. We knew there was an opportunity to make some changes and largely to simplify. The first time around, the site was a pretty big success. When it came time to reassess, what was the core mission? It boiled down to being a strictly consumer site."

"Before we made any decisions on what the site was going to be, we did a lot of research into the population we were going to try to reach," explained Booth. "One of our goals was to reach a much younger demographic," said Booth. "That pointed us to doing mobile. Mobile is growing, representing about 10 percent of the traffic to medicare.gov now."

The goal of speaking clearly to the people that HHS is trying to reach drove a series of choices for design and content.

"One of the things we saw was the need to explain the project really clearly to people, not to introduce other topics that might be confusing," said Booth. "The marketplace program was separate. We've moved away other parts, like the text of the law or implementation timeline. It's important to keep those materials online but on other properties. Policy guidelines also were moved over to other websites. We needed something that could speak clearly to the people we're trying to reach."

In design, choosing what not to include is as important as what elements do appear. The involvement of Teal Design early on and Edward Mullen throughout, focusing on user experience, made a difference in how Healthcare.gov looks and works on a mobile device today.

Code for the people, with the people

Performance, citzen-centric design, and management aside, there's a deeper importance to how Healthcare.gov is being built that will remain relevant for years to come, perhaps even setting a new standard for federal government as a whole: updates to the code repository on Github can be adopted by every health insurance exchange using this code. (The only difference between different state sites is a skin with the state logo.) "We have been working in the .gov space for a while," said Gundersen. "Government people want to make the right decisions. What's nice about what Bryan [Sivak] is doing is that he's trying to make sure that everyone can learn from what HHS is doing in real-time. From a process standpoint, what Bryan is doing is going to change how tech is built. FCC is watching the repository on Github. When agencies can collaborate around code, what will happen? The amount of money we have the opportunity to save agencies is huge. Think about servers alone."

The impact of this reduction in infrastructure on costs was a point he made repeatedly.

"You can't underestimate the cost of complexity," said Gundersen. "If you think the servers are expensive, consider the team required to maintain them."

With Healthcare.gov, something quite important happened that could also be lost in the mix: Code developed for the people, by the people, was released back to the people.

"There's an important legal detail here," said Cole. "Public domain doesn't apply to works for hire and it doesn't apply to code developed by a contractor. Healthcare.gov and other code was developed under BSD, the most permissive license possible."

While the website, funding from the federal government paid for the improvement of a series of open source software tools that it itself used.

"It's nice when government doesn't just take from open source but contributes code back to the community," said Gundersen.

The choice that HHS made in working with Development Seed meant that upgraded code for that tool was released on Github for the use of the public, over the course of the project.

"All of those contributions were made in real-time on Github as they were developed," said Cole. "The code now pulls in Google Analytics to analyze content for popularity."

"We got 10,000 authenticated users through Github and more through repository," said Cole. "Recently, we did a complete redesign, adding mobile and responsive development. HHS paid for that development. They also paid for enhancement of other open source tools that people are already using." Collaboration and cascading updates aren't an extra, in this context: they're mission-critical.

"This was a really distributed team, with design done by another party," said Cole."It started with a 'lock in' that laid out architecture and design, then tech followed. We wanted something really agile, to get it right first and keep iterating. After four months of development, we put together a site that's responsive and multilingual, and did so scalably."

Sivak said that he expects the new site to continue to be improved iteratively over time, in response to how people are actually using it. "We're going to be collecting all kinds of data," said Sivak. "We will be using tools like Optimizely to do A/B and multivariate testing, seeing what works on the fly and adapting from there. We're trying to treat this like a consumer website. The goal of this is to get people enrolled in health care coverage and get insurance. It's not simple. It's relatively complex process. We need to provide a lot of information to help people make decisions. The more this site can act in a consumer-friendly fashion, surfacing information, helping people in simple ways, tracking how people are using it and where they're getting stuck, the more we can improve."

Sivak is a fan of the agile development methodology that has become part of start-up development everywhere, including using analytics tools to track usage and design accordingly.

Notably, the HHS team has been using feedback to drive design choices from the beginning, applying the "lean startup" model to development.

"We did rounds of usability testing, starting early on with a card sort for taxonomy," said Booth. "We built out wireframes and did testing on look and feel. From my point of view, that was informed by a mix of designers, then getting user feedback."

This approach may be maturing in the private sector but still feels novel in some parts of government.

"One thing that has been nice that isn't always there on federal projects was a lot of support from leadership to look at user feedback, watch what users tell us and then go from that," he said. "It's not about what someone's favorite color might be."

The work of the team at HHS earned some praise from their collaborators at Development Seed.

"It's not a case where they needed developers," said Cole. "They just needed to adapt an agile workflow, have a good conversation and manage requirements dynamically, not create a huge spreadsheet of what they wanted and come back in two months.

Open by default

Using Jekyll and Prose.io to build the new Healthcare.gov is the latest chapter in government IT's quiet open source evolution. Across the federal government, judicious adoption of open source is slowly but surely leading to leaner, more interoperable systems.

An open, agile approach to development gave Sivak and his team transparency into the status of the project through issue trackers on Github.

"Put yourself in Bryan's perspective, with his ability to know what's going on," said Gundersen. "He could just open up an issue tracker and look at what's been done, not wait for a briefing."

Talking at length with HHS' CTO, it's clear that he's happy with the process and outcomes, though he emphasized repeatedly that the site will continue to improve. "The thing that Git is all about is social coding," said Sivak, "leveraging the community to help build projects in a better way. It's the embodiment of the open source movement, in many ways: it allows for truly democratic coding, sharing, modifications and updates in a nice interface that a lot of people use."

Sivak has high aspirations that publishing the code for Healthcare.gov will lead to a different kind of citizen engagement. "I have this idea that when we release this code, there may be people out there who will help make improvements, maybe fork the repository, and suggest changes we can choose to add," he said. "Instead of just internal consultants who help build this, we suddenly have legions of developers."

The long game for the code behind Healthcare.gov may be quite interesting, given the status of exchanges in the states. If their health insurance exchanges aren't ready or robust, they can simply pull this code and adopt it. While states and federal government sharing code might make for fertile fodder for constitutional scholars and philosophical discussions of federalism in the future, for the moment, the stakeholders all just need something that works.

"This is multi-lingual, 508-compliant, and hits on mobile," said Gundersen. "So many states and fed agencies can look at this as part of a new, different way of building websites. Part of that is process-based, from the start, using tech that is faster and more flexible."

In fact, Booth says that there have already been a couple of states that have asked CMS if they can pull the code on their sites.

"We don't have to ask if you're on Microsoft, Unix or Application Server Pages," he said. "It's on Github and you can pull it down. Open source is not always applicable but when it is, it's very powerful."

Not everything is innovative in the new Healthcare.gov, as Nick Judd reported at TechPresident in March: The procurement process that led to Development Seed is complicated, with some potential conflicts of interest present. The end result, however, is a small startup in a garage in DC collaborating with the federal government to relaunch one of the most important federal websites of the 21st century in a decidedly 21st-century way: cheaper, faster and scalable, using open source tools and open standards.

"This is the responsive Web of structured data," said Mullen. "Create once, publish everywhere."

That's a huge win for the American people, and while the vast majority of visitors to Healthcare.gov this fall will never know or perhaps care about how the site was built, the delivery of better service at lowered cost to taxpayers is an outcome that matters to everyone.

"Open by design, open by default," said Sivak. "That's what we're doing. It just makes a lot of sense. If you think about what should happen after this year, all of the states that didn't implement their systems, would it make sense for them to have code to use as their own? Or add to it? Think about the amount of money and effort that would save."

The Pew Research Center's Internet Project is pleased to offer scholars access to raw data sets from our research. All uses of this data should reference the Pew Research Center as the source of the data and acknowledge that the Pew Research bears no responsibility for interpretations presented or conclusions reached based on analysis of the data.

Our data sets are made available as single compressed archive files (.zip file). Pew Research is interested in learning about other ways that scholars use our data. If you publish something based on our data, please let us know by sending us an email. Individuals will need to fill out a brief registration before downloading data. Questions concerning the data sets may be directed to the Pew Research Center.

Since his first full day in office, President Obama has prioritized making government more open and accountable and has taken substantial steps to increase citizen participation, collaboration, and transparency in government.

Data.gov, the central site for U.S. Government data, is an important part of the Administration's overall effort to open government.

Open Data in the United States

A large number of cities, counties, and states have open data sites.

Download the full list of Open Data Sites in the following formats: [ CSV] | [ EXCEL]

A number of local governments in the United States have launched their own sites with access to machine-readable data.

U.S. States

U.S. Cities and Counties

Open Data Internationally

Nations around the world have followed the example of Data.gov in opening up a wide variety of data for citizens and businesses. Download the full list of open data sites in the following formats: [ CSV] | [ EXCEL]

Open Source

Data.gov was built with open source software, CKAN, and WordPress. Anyone, especially local, state, and foreign governments are welcome to borrow the code behind Data.gov.

You'll find over 1 million statistics from over 600 areas on our portal: market data, consumer data, revenue figures and trends. Our customized search enables you to find what you're looking for in a quick and easy way.

Publications

If you find yourself curious to learn more about an industry but simply lack the time to research, our industry reports can help you out. In 40 pages you'll gain a complete and comprehensive insight into the latest key figures, developments, trends and forecasts relating to the industry of your choice.

Recently Naval Ravikant, cofounder of the startup network AngelList, said he was "selling his cars" in favor of using Uber and other transportation services. He calculated that his BMW 3-series convertible cost him $1200-$1500 per month: $300 garage at work, $300 garage at home, $600 car payment, $200-$300 registration, fuel, insurance, and maintenance. He uses uberX 3x per day (~$54/day; fewer times on weekends). He adds, "I can relax in the back on phone or iPad, no road rage on arrival, no hunting for parking, door to door service."

So what do the economics of such a decision look like? While I've done this before for taxis, cars are more complex.

In this post we look at how much owning a car in San Francisco really costs and compare that to using Uber instead.

Cars are tricky beasts because, much like housing, the decision to own one is often not one of economics (even though housing and transportation are top two expenses in the average American's budget). Clearly there are cheaper options to owning a car. However public transportation is limited and, in San Francisco at least, MUNI can be unreliable with only a 52.7% on-time rate. There's a strong psychological factor to car ownership as well, and a status signal.

In fact, a 2010 British Journal of Psychology study, the "Effect of manipulated prestige-car ownership on both sex attractiveness ratings", experimentally tested the perceived attractiveness effect cars have. The study had heterosexual men and women rate the perceived attractiveness of the opposite sex. Researchers manipulated the surrounding environment in the photographs of the men and women receiving the ratings such that the people were shown seated in either a Bentley Continental GT or a Ford Fiesta ST:

Okay, here are actual examples of the stimuli used:

Overall, men tended to rate women as more attractive than women rated the men. Car type had no effect on how men rated women's attractiveness, but women rated men pictured in a Bentley Continental as more attractive than the same men pictured in a Ford Fiesta ST. Here are the results in bar chart form:

This tells us that there is a certain status appeal to being in a nice car. With those psychological effects in mind, let's now look at the economics of car ownership in the Bay Area. The true cost of car ownership has to account for real-world costs including depreciation of car's value, fuel, insurance, maintenance and repair, taxes and fees, etc.

Owning a car costs somewhere between $5,000 and $15,000 per year.

Cars depreciate in value. A lot. New cars really are pretty bad financial decisions (but of course, it's not just about the finances). Unsurprisingly, this cost scales with income, as people with more money buy more expensive cars that are also more expensive to own and operate. Meaning Uber's demographic probably tends toward the higher end of the $5,000-$15,000 range. Of course these numbers depend on the type of car, driving habits, etc., so caveat lector.

The estimates do not account for parking, tickets, and tolls, which also tend to be pretty high in San Francisco ( which is among the expensive places to park in the US).

For those who drive, their daily commute averages around 50-60 minutes roundtrip, and public transportation users spend almost twice as long each day getting to and from work. Only about 15% of San Franciscans use public transportation to get to work.

Given all of this information, how does Uber compare? Well by January 2013, the average SF driver partnering with Uber took only 2 min 40 sec to arrive after they agreed to pick you up.

This means that the average wait time for an Uber is essentially no more than what it would take you to walk to your car and start it up yourself. And far better than what you'd get compared to calling a cab (good luck) or even with a street hail. There's a hugely significant time savings with using Uber. Is it worth it? The answer to that depends on the cost.

So how much does Uber cost? Again, for San Francisco, the median fare is only $22. For uberX it's $17. That means that 50% of uberX trips cost less than $17 (and 50% more) but you can expect to pay around $17 for any given trip. The math here is simple:

Ditch your car, and you save enough money every year to afford up to 882 uberX rides per year.

That's enough to use Uber to get to and from work each and every day, with another 382 trips left for whatever else you wanted to do. That's enough to support an Uber-only transportation model. Even at the lower end of car ownership costs of $5,000/year, which I think is fairly unlikely for San Francisco, that comes out to 292 uberX rides per year.

The math doesn't lie. In a city with with a fast, practical (and cool) alternative like Uber, it would very much be worth your time to crunch the numbers and see how much you're really spending on your gas, parking, maintenance, etc. and how much time you spend doing those things. Because having your own personal driver pick you up in a slick car each and every day is a hell of an appealing alternative.

Standard & Poor's Industry Surveys track more than 50 North American industries and 10 Global Industries and are ideal for management consultants, strategic planners, money managers, public and academic libraries, students, and business faculty. Standard & Poor's Industry Surveys enable readers to think and act like industry insiders.

Each report is authored by a Standard & Poor's industry research analyst and includes information about the current industry environment, industry trends, key industry ratios and statistics, how to analyze a company, a glossary of terms and a comparative company financial analysis.

Subscribers to Standard & Poor's Industry Surveys also receive Standard & Poor's Trends & Projections, which is a monthly newsletter written by Standard & Poor's top economists that offers insight and commentary on macroeconomic topics such as GDP growth, inflation, unemployment, interest rates, and the stock market.

Subscribers access Standard & Poor's Industry Surveys via MarketScope Advisor or NetAdvantage.

Offered by Equity Research Services

3 years ago, we published a report on 2011 Facebook Demographics & Statistics that covered gender, location, education, and more (US only). Recently we dove into Facebook's Social Advertising platform to get a refreshed snapshot of the same data points to see what exactly has happened over time and to look at the numbers behind many recent claims: teenagers are leaving by the millions. Enjoy!

Top Insights:

Top Insights: 1) Teens (13-17) on Facebook have declined - 25.3% over the last 3 years.

2) Over the same period of time, 55+ has exploded with + 80.4% growth in the last 3 years.

3) Of the major metropolitan areas, San Francisco saw the highest growth with + 148.6%, a stark contrast with Houston which saw + 23.8% growth.

We also took a closer look at the Teens (13-17 year olds) and the Folks (55+) to get a better understanding of their current representation on Facebook. Here you go:

UPDATE - Thanks for all the feedback and comments on this post, here's a quick clarification:

Many have commented on the fact that "Teens" (age 13-17 in this post) as we recorded in 2011 have now grown into the 18-24 year old demographic. While that's true, the primary point of this post was simply to draw attention to the fact that Facebook's Social Advertising platform shows 3 million fewer addressable 13-17 year olds today compared to 2011.

Mobile Commerce

This report explores the continued evolution of the online shopper and the impact of the mobile shopper. Download our report today for insights, tips and recommendations to help retailers and brands prepare for the shift into m-commerce. Free download >

Channel Optimization

This ebook focuses on four crucial areas of digital marketing and gives you the knowledge and tools you'll need to support you on your journey to marketing optimization.

Free download >

Path to Purchase

Today, the consumer path to purchase is as complex as ever. Shifting consumer attitudes and multiple connected devices create a chaotic reality. This ebook gives marketers context and insight into the evolving path to purchase as well as advice on building a strategy to better shape their marketing efforts. Free download >

Advertising ROI

Ad Impact quantifies the lift achieved by online advertising. Marketers, publishers and advertising agencies can pair Ad Impact with their own media budget data to calculate campaign ROI and separate winning strategies from ineffective strategies. All data and analyses are presented in a concise, easy-to-read and easy-to-share format. Learn more >

Competitive Benchmarking

Online Channel Effectiveness (OCE) allows brands and websites to develop online growth and channel strategies that guide consumers towards deeper online marketing interactions. OCE enables marketers to reverse-engineer their competitors' online performance to optimize their own online marketing, sales, service and loyalty programs. Learn more >

Campaign Optimization

Through a real-time dashboard, agencies and advertisers can address, in-flight, how a campaign is reaching and impacting the audiences they care about most and optimize the delivery of visible ads to a specific audience, creating behaviors and attitudes that drive purchase intent. Learn more >

welcome

ChangeDetection.com provides page change monitoring and notification services to internet users worldwide. Anyone can use our service to monitor any website page for changes. Just fill in the form below, we will create a change log for the page and alert you by email when we detect a change in the page text. We've been doing it since 1999. It's free.

monitor a page

recent changes to the internet

HTML changes are shown hilighted on the original version of the HTML document

A block of text is returned with spans indicating existing, new, and deleted text. Text is ellipsed and limited in size.

A block of text is returned with spans indicating existing, new and deleted text. All text is included.

log in

search

Copyright 1999-2010 FreeFind.com. ChangeDetection and ChangeDetection.com are trademarks of FreeFind.com.

home faq policies contact website panels tag reference

Site search technology provided by FreeFind.com and Findia.Net net search

Office of Trade Policy & Analysis

Browse by Subject

Our Offices

International Trade Statistics

Trade Policy Information System

Tables profiling state imports by product and market of origination.

Infographic: U.S. Trade in Services, 2012

Free Trade Agreement Trade Tables

Infographic: Benefits of Trade Agreements, 2013

Small and Medium-sized Companies

Small & Medium-Sized Exporting Companies: Statistical Overview, 2011

A report analyzing 2011 data from the Census Bureau.

Tables profiling SMEs (small & medium-sized enterprises) by market, product, and U.S. state.

Sub-National Trade Statistics

For all 50 states, export data on industries and major markets; percentages of export-related jobs; numbers of companies that export; and how foreign investment influences exports.

Exports from U.S. Metropolitan Areas

Metropolitan Export Series Database

Tables containing merchandise export values for 367 metropolitan areas. The series includes metro area exports as a percent of the state total, where possible; product exports to individual countries for the 50 largest metropolitan areas; top global export product categories; and total exports to ten regional destinations.

Manufacturing Statistics

Tables showing jobs by state and by industry.

Shows market indicators for the following U.S. manufacturing trends for current period and year-to-date: wage rates, profits, employment, production, capacity utilization, productivity, exports, goods shipments. Includes supporting documentation, tables, and charts.

For more information please contact: Michael Greene

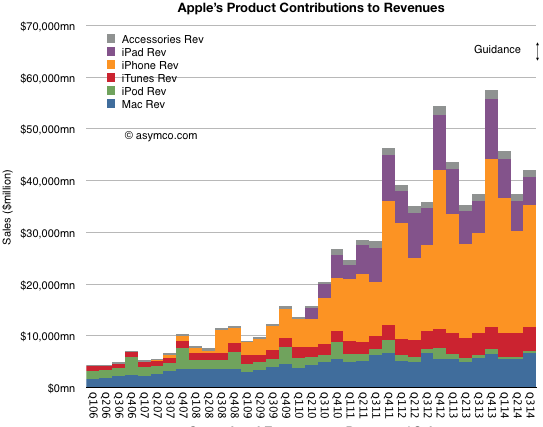

Apple has declared that what used to be "Other Music Related Products and Services"[] plus "Software, Service and Other Sales"[] which was formerly known as "iTunes/Software/Services"[] is about to become "Services".

"We'll also have a category that we refer to as services and this will encompass everything we report under the heading of iTunes software and services today including content, apps, licensing and other services and beginning this month it will also include Apple Pay."

"Services" will therefore encompass a massive amount of revenue. The reported revenues for the fiscal 2014 were $18 billion. Including all billings, the turnover in sales is over $28 billion. For next year, assuming that Apple Pay, which is just getting started, is unlikely to contribute greatly to revenues, Services turnover will top over $35 billion. That figure would make Apple Services alone one of the top 90 companies in the Fortune 500.

Regardless, as a component of overall sales, the group formerly known as iTunes/Software/Services (shown in red above) was a modest 7% of total sales in the last quarter. Using all available information regarding downloads, payouts and reported financials, an estimate can be obtained on how this 7% is itself divisible into nine sub-segments:

Notes:

What motivates a company to destroy its brand?

We start with Mini's plans to sell 100,000 cars in the States by 2020, nearly double today's pace and remember how Cadillac destroyed their brand and how Mercedes, Porsche, Ferrari et. al. can't wait to do the same.

Also, might retail power in the form of strong dealer regulation limit brand's ability to improve or address customer experiences? What motivated Warren Buffet to enter the American car dealer business? (With a long aside on what Buffett investment logic is all about and why it's not contradictory to a growth investor).

via Asymcar 19: About that Ferrari SUV... | Asymcar.

Horace and Anders discuss Apple Watch pricing, Consumerism and Planned Obsolescence. In the closing segment Horace presents a new dichotomy of company values.

via 5by5 | The Critical Path #130: Determinism vs. Probabilism.

We talk about Samsung, Apple Pay (vs. CurrentC) and Xiaomi.

via 5by5 | The Critical Path #129: The Right Incentives.

When the Apple Watch was launched, all eyes turned to the Swiss watch industry. Analysts measured it and asked if it's big enough to be interesting. Industry observers questioned the competitiveness of an entrant vis-à-vis the ancien régime. Marketers weighed in with segmentation hypotheses and how Apple's queer new device might best fit.

These are all mistakes in analysis.

The market for Apple Watch is not the Swiss (or Chinese) watch market. The market for Apple Watch is the number of wrists in the world. To the extent that those wrists will be covered with Apple hardware will determine whether it is successful or not.

Measuring the existing market is a mistake because the existing products are hired for different jobs. Those measurements will yield only an answer to how big that job is.

Assessing competitiveness vs. incumbents is a mistake because incumbents have perfected solving the problems of wrist-worn timekeeping devices over a century. Apple's watch is not a wrist-worn timekeeping device any more than the iPhone is a phone or the iPad is a pad.

Segmenting the market by whatever means are convenient today is irrelevant because the segments are currently positioned on the current jobs to be done. It's no more relevant than classifying the iPhone along the segments defined for phones in 2007.[]

Some have tried to wedge the Apple Watch among the "fitness tracker" market. This is no more plausible given that fitness tracking is no more interesting than timekeeping is to Watch.

The best way to measure the opportunity is to quantify the "wrist-space-time" continuum and deciding what is and what isn't addressable. The wrist is an interesting place to put a computer and Apple makes computers. The rest is left as an exercise to the reader.

Notes:

Ben Bajarin:

A few weeks back Horace Dediu of Asymco and I were having dinner and we got to discussing some of this updated thoughts on disruption theory. One bit in particular was how the luxury tech market was causing him to evolve some thinking on the theory as it relates to consumer markets. I thought it would be great to have him on and we could chat more about disruption and the role it plays in the technology industry in the 21st century.

via Podcast: Discussing Disruption Theory | Tech.pinions - Perspective, Insight, Analysis.

Samsung's smartphone ascent was breathtaking. From having essentially zero market share in the category in late 2010 to becoming the largest vendor took less than two years. In doing so it grew to become the largest phone vendor, smart or not-a goal which eluded them during the previous decade of effort. Samsung went on to capture not only the lion's share of unit volumes, they also took almost all the profits in the Android mobile phone market.

And in a market filled with competitors. Literally hundreds of vendors and thousands of products were available at every conceivable price point. Samsung did away with HTC, LG, and Motorola. HTC, the first Android vendor (and first to market with Windows Mobile), Motorola, Google's launch partner in the US and "Droid" brand partner (and future owner). Google's own Nexus products. Samsung Galaxy ruled them all.

Galaxy swamped the Chinese market and the Indian market, the largest in the world. They were so powerful that they were singled out both by Microsoft and Apple for IP royalties.

All within two years or the average life-span of one smartphone.

But something went wrong in 2014. Growth in shipments suddenly stopped. This was not a problem with the overall market, which kept growing. The slowdown did not affect other vendors, especially the up-and-coming Lenovo and Xiaomi and the second and third tier vendors whose names are known only in the local markets they serve.

The result of this slowdown is shown in the following graphs:

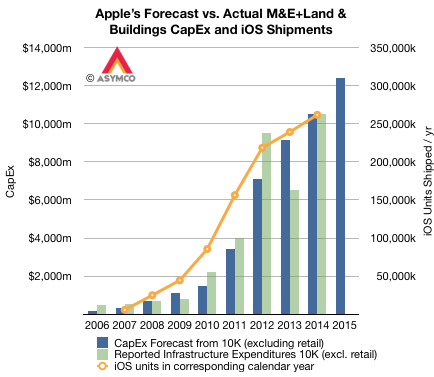

12 months ago I asked How many iOS devices will be produced in the next 12 months?

Based on the analysis of Capital Expenditures (as forecast by Apple in their annual 10K report) I concluded "iOS unit shipments should be between 250 million and 285 million."

The answer turned out to be 247 million.[] Including Apple TV the total would probably be around 251 million.

Since last year, I adjusted my model by observing corresponding iOS unit shipments for the calendar year corresponding to each fiscal year. Since the calendar year is offset by one quarter (FQ1 = CQ4) looking at calendar year means looking forward one quarter post-spending. I believe this is more accurate as spending generally happens in advance of production.

The resulting pattern is shown below:

Notes:

We go over Apple's last earnings report. Is significant growth conceivable for the next quarter? Plus the new iMac and the end of visible pixels.

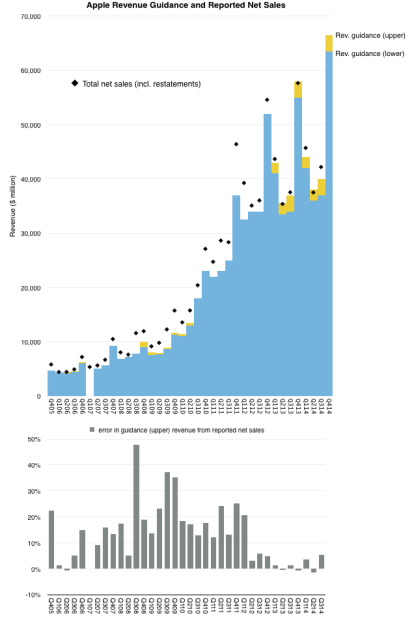

via 5by5 | The Critical Path #128: The Upper End of Guidance.

In Q3 2014 Apple's revenues were 5.3% higher than the upper end of their guidance. This is the highest error in guidance since the new range-bound reporting regime started two years ago.

The following graph shows the guidances given since 2005 and the actual revenues. The error (as a percent of upper guidance) is given in the second graph.