The Successful Leader (Part I)

Culture is hot. In our discussions and work with leaders in business, government, and not-for-profit organizations, we have observed a markedly increasing emphasis on culture-for a host of reasons.

Leaders trying to reshape their organization's culture are asking: How can we break down silos and become more collaborative or innovative? Others, struggling to execute strategy, are wondering: How do we reconnect with our customers or adapt more proactively to the new regulatory environment?

Leaders overseeing a major transformation want to know how to spark the behaviors that will deliver results during the transformation-and sustain them well beyond. Those involved with a postmerger integration grapple with how to align the two cultures with the new operating model-and reap the sought-after synergies. And those simply seeking operating improvements often ask: How can we become more agile? Accelerate decision making? Embed an obsession for continuous improvement throughout the organization?

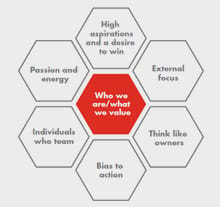

Regardless of the reasons, there's little debate about what culture is. Most agree that it's the values and characteristic set of behaviors that define how things get done in an organization. Nor is there any debating culture's importance. Most leaders recognize how critical a high-performance culture is to their organization's success. But many are discouraged by the yawning gap between their current and their target culture. Others are frustrated because they don't know why their culture is broken (or just suboptimal)-or what steps they might take to get and keep a high-performance culture.

Through our work with clients, we have found that culture change is not only achievable but entirely feasible within a reasonable amount of time. Any organization that is willing to make the necessary effort can realize its target culture by implementing change based on the answers to four questions:

While these questions seem fairly straightforward, they are often shrouded in myths. These myths create the hurdles that make the goal of a high-performance culture seem so elusive.

"Maintaining an effective culture is so important that it, in fact, trumps even strategy."

Culture. It's probably a word you hear often if you follow blogs on entrepreneurship or read articles on business and management. But what is it exactly?

According to Frances Frei and Anne Morriss at Harvard Business Review:

"Culture guides discretionary behavior and it picks up where the employee handbook leaves off. Culture tells us how to respond to an unprecedented service request. It tells us whether to risk telling our bosses about our new ideas, and whether to surface or hide problems. Employees make hundreds of decisions on their own every day, and culture is our guide. Culture tells us what to do when the CEO isn't in the room, which is of course most of the time."This post will cover all of the elements that make great culture. Each culture has different tactics and unique qualities. But, universally, culture is about the employees and making sure they have a fun and productive working environment.

Let's dive in.

Why Should You Care about Culture?

The workplace should not be something that people dread every day. Employees should look forward to going to their jobs. In fact, they should have a hard time leaving because they enjoy the challenges, their co-workers, and the atmosphere. Jobs shouldn't provoke stress in employees. While the work may be difficult, the culture shouldn't add to the stress of the work. On the contrary, the culture should be designed to alleviate the work related stress.

This is why culture matters. Culture sustains employee enthusiasm.

You want happy employees because happiness means more productivity. And when a business is more productive, that means it is working faster; and when it works faster, it can get a leg up on the competition. So it's worth the investment for companies to build and nourish their culture.

Culture is also a recruiting tool. If you're looking to hire talented people, it doesn't make sense to fill your office with cubicles and limit employee freedom. You'll attract mediocre employees, and you'll be a mediocre company. If, on the other hand, you have an open working environment with lots of transparency and employee freedom, you'll attract talent. From the minute people walk in the office, they should know that this is a different place with a unique culture.

When you put a focus on culture, you'll have guiding principles. People will know you for this. Employees will live by it. It'll help get you through difficult times. You'll base hiring and firing decisions on the principles. It'll help get all employees working on the same company mission. In some sense, it's the glue that keeps the company together.

A company culture that facilitates employee happiness means lower turnover and better company performance. Employees are loyal and companies perform better. It's a win-win.

If your company ramps up to more employees, the culture will become a self-selecting mechanism for employees and candidates. The people who would fit into your culture become attracted to it and may end up with a job. For example, at Amazon, they look for inventors and pioneers. People who want to work there know this and are attracted by it.

Now, let's get into the elements that make great company culture...

1. Hiring People Who Fit Your Culture

Tech Journalist Robert Scoble meets with a lot of CEOs. And when talking about hiring decisions, they always try to make sure they don't hire jerks. It's for this reason that companies have such a rigorous hiring process. Some companies like to bring job candidates in to work with their employees for a week. They give the candidates a project and see how they work and how they work with others.

In a post on Harvard Business Review, Eric Sinoway breaks down types of employees and how they impact company culture. The high performing employees who don't fit into your culture are known as vampires. These vampires must be terminated because, while performance is solid, they're attitude is detrimental to company culture, which is detrimental to business.

Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh, one of the strongest advocates of culture, makes a great point when he notes that the people you hire represent your company even outside of work. If you meet someone and they tell you where they work, your perception of that place will change based on your opinion of the person. If they're nice, you'll view the company in a positive light. If they're a jerk, you won't view the company favorably. This effect can be even greater when it's a company you've never heard of and didn't previously have any opinion of. If the person is helpful, you'll view the company as helpful. This is why it's important to hire people who share your company's values.

One bad hire can affect an entire department and possibly dozens of customers. And it can happen quickly, acting like a virus that spreads. The employees will talk about the bad hire; and if action isn't taken, it can get much worse.

But the good thing is that any damage can be reversed. And more than that, your values can be reinforced at the same time. If you release that toxic employee (the vampire), it'll show other employees that you appreciate them and are serious about your culture.

2. Having Employees Know the Values and the Mission of the Company

There's a question that often gets asked in job interviews:

Why do you want to work here?The purpose of the question is to provide the interviewer with a sense of what the interviewee knows about the company. If the interviewee can provide a specific, pointed reason for why they want to join that company, it shows the interviewer they've done research on the company and may be a fit for the position.

Of course, an interview will show only so much. A person can be whoever they want to be for 30-60 minutes. The only real way to know if someone is on board with the values and mission of a company is to watch them work for an extended period of time. Do they follow the same values in their personal life? This is why you need to really get to know the serious candidates.

Zappos has their core values. They guide how employees work and enjoy their personal lives.

When employees are passionate about the values and mission (like organizing the world's information at Google), they are dedicated to accomplishing the goal.

In a video on the Facebook Careers page, Mark Zuckerberg says:

"The reason why we've built a company is because I think a company is by far the best way to get the best people together and align their incentives around doing something great."At Facebook, it's about making the world more open and connected. These drive the employees, guide the product, and energize the entire company. If an employee isn't committed to the mission, it just becomes another job. And when it's just another job, it usually means the employee isn't happy.

On the other hand, when the employee is on board with the mission, they're engaged in the job and want to help the mission succeed, thus helping the company succeed.

3. Knowing That Good Decisions Can Come from Anywhere

No one has all the answers. A company where only management makes decisions is a surefire way to send A and B players away to other companies.

As some companies get bigger, they tend to limit employee freedom. The employees are less and less involved in key decisions and their impact on the business is drowned out. It becomes a part of the culture. Employees go to work, do what they're told, and just help someone else achieve their dream. The worker's impact on the business is minimal and they become "just another employee at just another company." And for some people, it's all they want: go into work, take orders, do the job, and wait for the clock to hit 5:00 P.M.

But this is not what the best employees want.

They want to have a voice and a meaningful impact on the company and its direction. They know that anyone can win a debate with the most senior person at a company. They also know they can create tools for the company without the need for management approval.

For instance, the Google News tool was created by a research scientist at Google named Krishna Bharat. Creating Google News wasn't something that came from a management meeting and descended upon Bharat. He invented it after the September 11 attacks because he figured "it would be useful to see news reporting from multiple sources on a given topic assembled in one place." It came from a problem that he was having; he wasn't instructed to create it.

Companies have greater success when employees are given this type of freedom that isn't ruled by a hierarchy, assuming they're talented employees who fit the culture. Knowing that good decisions can come from anywhere and expanding employee freedom are cornerstones of attracting talented individuals who will fit into the culture if you let them.

4. Realizing You're a Team and Not a Bunch of Individuals

Ever notice how many CEOs refer to their employees as a "team"?

On the Instagram jobs page, they refer to themselves as a team, not a company.

Quora has a "Team" page, not an "Employees" Page:

Refer.ly invites people to "Join Our Team":

The difference between being a team and just a bunch of individuals is that the individuals see themselves as separate from each other. Helping others is forced because you normally operate on your own projects, or your own part in a larger project.

Teams work together on all work related projects and help where necessary. It doesn't matter who gets credit for what because you accomplish everything together. You're knit together, not separated.

If you watch sports, you see how teams function. They work together (in the form of passes and assists), encourage each other, and communicate regularly (communication on the sidelines when they're not playing). There are always a few who get accused of putting themselves before the team, known as a ball hog in basketball. This is because they "hog" the ball and don't involve any of their teammates in the offense. This impairs the offense which cannot work at 100% because not all 5 players are fully involved.

These people are usually dealt with appropriately at the direction of the head coach. They usually see decreased playing time or are cut from the team. Teams work best when everyone is on board, feeding off each other, and playing together. If you have a bunch of individuals, or ball hogs, they'll break down from conflicts, become ineffective, and then irrelevant. Teams are the best and most efficient way to get things done.

Stay Tuned...

In the coming weeks, we'll be profiling different company cultures. We'll take a look at Google's culture and what makes it so effective and unique. We'll examine Zappos and their customer service centered culture, Facebook's engineering heavy culture, and many others. Stay tuned for more!

What other elements are important for company culture? Let me know in the comments!

About the Author: Zach Bulygo is a blogger for KISSmetrics, you can find him on Twitter here.

I often ask business leaders three simple questions. What are your company's ten most exciting value-creation opportunities? Who are your ten best people? How many of your ten best people are working on your ten most exciting opportunities? It's a rough and ready exercise, to be sure. But the answer to the last question-typically, no more than six-is usually expressed with ill-disguised frustration that demonstrates how difficult it is for senior executives to achieve organizational alignment.

What makes this problem particularly challenging is a number of paradoxes, many of them rooted in the eccentricity and unpredictability of human behavior, about how organizations really tick. Appealing as it is to believe that the workplace is economically rational, in reality it is not. As my colleague Scott Keller and I explained in our 2011 book, Beyond Performance, a decade's worth of data derived from more than 700 companies strongly suggests that the rational way to achieve superior performance-focusing on its financial and operational manifestations by pursuing multiple short-term revenue-generating initiatives and meeting tough individual targets-may not be the most effective one.

Rather, our research shows that the most successful organizations, over the long term, consistently focus on "enabling" things (leadership, purpose, employee motivation) whose immediate benefits aren't always clear. These healthy organizations, as we call them, are internally aligned around a clear vision and strategy; can execute to a high quality thanks to strong capabilities, management processes, and employee motivation; and renew themselves more effectively than their rivals do. In short, health today drives performance tomorrow.

Many CEOs instinctively understand the paradox of performance and health, though few have expressed or acted upon it better than John Mackey, founder and CEO of Whole Foods. "We have not achieved our tremendous increase in shareholder value," he once observed, "by making shareholder value the only purpose of our business."

In this article, I want to focus on three other paradoxes that, in my experience, are both particularly striking and quite difficult to reconcile. The first is that change comes about more easily and more quickly in organizations that keep some things stable. The second is that organizations are more likely to succeed if they simultaneously control and empower their employees. And the third is that business cultures that rightly encourage consistency (say, in the quality of services and products) must also allow for the sort of variability-and even failure-that goes with innovation and experimentation.

Coming to grips with these paradoxes will be invaluable for executives trying to keep their people and priorities in balance at a time when cultural and leadership change sometimes seems an existential imperative. Just as a circus performer deftly spins plates or bowls to keep them moving and upright, so must senior executives constantly intervene to encourage the sorts of behavior that align an organization with its top priorities.

Change and stability

Organizational change, obviously, is often imperative in response to emerging customer demands, new regulations, and fresh competitive threats. But constant or sudden change is unsettling and destabilizing for companies and individuals alike. Just as human beings tend to freeze when confronted with too many new things in their lives-a divorce, a house move, and a change of job, for example-so will organizations overwhelmed by change resist and frustrate transformation-minded chief executives set on radically overturning the established order. Burning platforms grab attention but do little to motivate creativity. Paradoxically, therefore, change leaders should try to promote a sense of stability at their company's core and, where possible, make changes seem relatively small, incremental, or even peripheral, while cumulatively achieving the transformation needed to drive high performance.

A large universal bank provides a case in point. Given the tumult in the financial-services sector in recent years, it needs to change, and change profoundly. But the cry of "let's change everything" will be counterproductive in an organization where staff members are mostly hard-working, committed people operating processes that involve millions of transactions per hour.

One large automotive company I'm familiar with, buffeted by three different owners and five different CEOs in the last decade, has recently embraced this paradox with a new management model dubbed "balance," a word loaded with meaning in the automotive industry because of its association with reducing drag and increasing speed. The simple idea behind the model is that any changes to a company's systems, structures, and processes should always be introduced in a consistent way, typically quarterly, as part of an explicit change package. If a proposed change isn't ready in time for one of these regular releases, it is either deferred to the next one or abandoned.

Previously, leaders of each of the company's functions had been inclined to introduce, on their own, changes they thought might generate value-for example, finance would launch a program to make costs variable, HR would announce an initiative to shake up performance management and compensation, and manufacturing would bring in new vendor-management systems. Hapless middle managers found themselves in a blizzard of change that made it difficult to focus on the organization's top priorities. Now, before change programs are rolled out more broadly, all of them are integrated, and the resulting complexities are addressed at the top of the organization.

In this way, the company's underlying operating model has remained more stable than it would otherwise have been, and more stable than it used to be when changes were announced in an uncoordinated fashion. Managers now understand and accept the rhythm of change, while managers and employees alike have gained new confidence that the different elements in the releases will be complementary and coherent.

The result is that a well-intentioned but disjointed flow of unending change has been converted into a well-structured one. Moreover, after years of lagging behind industry peers, the company has shortened its product-development cycles and increased the quality of its products. And it is running much more smoothly, with 20 percent fewer managers.

Control and empowerment

All organizations need at least a thread of control to link those who own the business to those charged with implementing its objectives. Companies that neglect mechanisms that enforce discipline, common standards, or compliance with external regulation do so at their peril. The share price of one global energy group, for example, collapsed when it came to light that poor oversight had allowed internal analysts to develop metrics based on optimistic assumptions and to overstate the company's oil and gas reserves substantially.

Yet excessive control, paradoxically, tends to drive dysfunctional behavior, to undermine people's sense of purpose, and to harm motivation by hemming employees into a corporate straitjacket. The trick for the CEO-cum-plate-spinner is to get the balance right in light of shifting corporate and market contexts. In general, a company will probably need more control when it must actually change direction and more empowerment when it is set on the new course.

The story of how a major global technology company recovered from a crisis four years ago is instructive. Forced to write off more than $2 billion of unmanageable contracts-and facing insolvency-a new management team took drastic and decisive action to strip out costs, renegotiate old agreements, change established practices, and impose stringent new controls. The company (with more than 100,000 employees) was saved but in the process found that it had lost the ability to deliver on its top priority: creative new ideas that would fuel organic growth. That's because an unintended consequence of the much-needed cost reductions had been the emergence of a "parent-child" relationship between the company's top team and middle managers. These managers had become so used to being told what to do, and had been given so little room to maneuver, that they eventually lost the ability to experiment. The "tree" of top management had grown so large that nothing could grow in its shade.

This company's solution was to introduce an "envelope" leadership approach, which first involved defining a set of borders. Employees could not go beyond them, but within them there was almost complete freedom to innovate and grow. Other businesses have attempted to copy the envelope idea but few have had the success of this global technology company, whose approach had real teeth. The flame of empowerment was fanned by first identifying some 600 leaders with the best capabilities and then rotating them around different businesses, with a mandate to shake things up. Meanwhile, the company's purpose, vision, mission, and values were all rewritten and drilled into leaders. Its "signature processes" (five core ones, where it aspired to be truly differentiated) were fundamentally reimagined. And evaluation and reward mechanisms were dramatically tightened to reward stars and actively manage people who seemed to be struggling. As the company added a greater degree of empowerment to the stricter controls-plates both balanced and spinning-its performance improved. Sales are growing again, and fresh energy is palpable throughout the organization.

Consistency and variability

Producing high-quality products and delivering them to customers on time and with the same level of consistency at every point in the value chain is critical to success in most industries. Variability is wasteful and time consuming, not to mention potentially alienating for customers. Most organizations therefore applaud behavior that attacks and eliminates it.

Yet in human terms, consistency too often hardens into rigid mind-sets characterized by fear of personal and organizational failure. It's been shown that we feel the pain of failure twice as much as we do the joy of success, so employees naturally tend to protect themselves and their teams, behavior that can inadvertently hamper innovation and calculated risk taking. After all, mistakes-from Edison's countless failed filaments to 3M's accidental creation of the adhesive behind Post-it notes-can sometimes be the mother of invention; as they say in the mountains, "If you're not falling, you're not skiing."

It's hard to think of a sector where it's more important to get the balance between consistency and variability right than it is in pharmaceuticals. Lives are at stake, and the development and launch costs of a new compound often run to billions of dollars. Faced with the approaching expiration of many licenses, one of the world's biggest pharma companies found that its tradition of reliability and consistency had become a limiting mind-set. Although it desperately needed to make new discoveries, a status quo bias took hold of the organization, which froze around a complex bundle of assurance, governance, and controls. Fear of failure and an obsession with getting these things right produced defensive 100-page PowerPoint presentations in abundance, but little meaningful product-development progress.

Behavioral problems didn't help, of course. An excessive "telling" rather than "listening" culture had degenerated into bullying; some senior executives literally shouted at their underlings. On one notorious "away day," a number of exercises revolved around cage fighting, a sport (dubbed "human cockfighting") that combines boxing, wrestling, and martial arts. The signal this sent from the top was that the culture really was dog eat dog.

Things came to a head when two scientists, frustrated by the time needed to get approvals, left to set up their own successful research business and were openly lauded by colleagues for breaking free of a stifling bureaucracy and dictatorial culture. The morale of those left behind suffered further, and energy drained out of the organization.

The solution the company devised combined building "slack" (additional people) into its resourcing-a bold move in austere times-with a direct attack on negative behavior. The worst offenders were removed, and it was made clear that cage-fighting attitudes were unacceptable.

Steps were taken to bump up the innovation rate by investing in smart people, but the top team went further. It set out fundamentally to alter what it called the organization's "social architecture" by building worldwide communities of scientists and encouraging exchanges between them across geographical boundaries and industry disciplines.

Successful experiments, to be sure, were more highly valued than failures, but both had their place in the company's culture. An emphasis in communications on "our wealth of ideas" promoted the simple notion that wealth (economic progress) arises from ideas (experimentation and innovation) and showed how carefully crafted language can help drive change. The result was an increase in the pipeline of products and, over time, a resumption of profit growth.

Embracing the paradoxes described in this article can be uncomfortable: it's counterintuitive to stimulate change by grounding it in sources of reassuring stability or to focus on boundaries and control when a company wants to stir up new ideas. Yet the act of trying to reconcile these tensions helps leaders keep their eyes on all their spinning plates and identify when interventions are needed to keep the organization lined up with its top priorities. Last, this approach makes it possible to avoid the frustration of many executives I've encountered, who pick an extreme: either they try to stifle complex behavior by building powerful and rigid top-down structures, or they express puzzlement and disappointment when looser, more laissez-faire styles of management expose the messy realities of human endeavor. Far more centered and high performing, in my experience, are those leaders who welcome the inconvenient contradictions of organizational life.

About the author

Colin Price is a director in McKinsey's London office.

Lessons on Leadership and Teamwork -- from 700 Meters Below the Earth's Surface

"We are well, the 33 of us, in the shelter." These words, written on a small piece of paper, created euphoria in Chile in early August and restored hope to the families of the 33 miners trapped in the San José copper mine in the heart of the Atacama Desert. The note emerged from a duct that is now used for communication with rescuers and for sending food and medicine to the miners, who are trapped 700 meters (nearly 2,300 feet) below the earth's surface in a small emergency shelter.

When the good news came to the outside that the miners were alive, a team led by engineer Andrés Sougarret labored to find the best alternative for reaching the tunnel of barely 30 square meters. The team was helped by experts in psychology, sociology, engineering and nutrition and by officials from NASA, who deal with similar situations of isolation encountered by astronauts. At first, it was estimated that the team would need four months for the rescue. Now, however, the Chilean government believes that it could extract the first miners in October, thanks to a tunneling machine able to drill through the surface of the earth.

Images recorded by the miners themselves have made clear the extreme conditions they are living under, and which they will have to bear until the rescue materializes: temperatures of up to 35 degrees Centigrade (95 degrees Fahrenheit); environmental humidity of 90% and rationing of food. Above all, it has become obvious that the miners are well organized. From the moment of the accident, they divided the shelter into zones devoted to an infirmary, recreational activity, food and dormitories. Some have assumed leadership positions that make survival possible. For example, Luis Urzúa Iribarren, who headed the shift of workers, assigned various roles to the other miners. One miner, Mario Sepulveda, received and handled cases of food and medication that arrived from outside the mine. From the outset, Victor Segovia wrote down everything that happened during and after August 5, the day of the disaster.

The skills and leadership exhibited by the miners will be crucial to their survival, experts say. In an interview with Universia Knowledge@Wharton, Francisco Javier Garrido, a professor of strategy in various MBA programs in Europe and the Americas and author of such management books as The Soul of Strategy, discusses the lessons that can be learned from their experience. Garrido is a partner and director of EBS Consulting Group (Spain-Chile), and managing director of the Business School at Universidad Mayor in Chile.

Universia-Knowledge @ Wharton: In your view, what have been the keys to the miners' survival, even when they didn't know if the outside world presumed them to be dead?

Francisco Javier Garrido: The keys to survival in an extreme experience such as this one ... can be summarized by three concepts [that] can be applied to the business world. First, there is the [background and expertise] of those who compose the group of people. [Those skills] have been vital for correctly understanding the context [the miners] find themselves in, as well as for grasping the real possibilities of being rescued. This has also been fundamental for keeping the group of people together and remaining hopeful about their chances to survive. Second, [the miners] figured out that it was vital to have [a leader] ... with the longest seniority in the ranks of the workers. This was critical for keeping the people on the team together [and] for creating trust in the possibility of emerging alive ... as well as [creating a system for] assigning tasks and the rationing of food.

It must be stressed that the components of experience and leadership are clear in this case. We need to point out the definition made by the head of the group, who acted as its spiritual guide. [He said] there was an upswing in what the [ancient] Greeks used to call "general wisdom." This happens whenever the people whom we recognize as capable of [best understanding] the working environment reach the best possible decisions for the group. Those are the people who carry the mandate for the best possible future ... on the battlefield or in the business world, where experienced managers play the same role.

UK@W: Do you believe that the importance of leadership -- and the role of the leader -- becomes clearer in crisis situations?

Garrido: These 33 men have given us a lesson not only in integrity, but in order and coordination. A spiritual leader has flourished: Luis Urzúa has taken charge of maintaining the cohesion of the group and keeping their spirits high. Meanwhile, the rest of the miners have contributed their own fair measure of effort ... in exchanging information with the rescue group; boosting their chances of survival by rationing food, and by paying special attention to those miners who are ... in the most precarious health, and [those] who are depressed. Without doubt, it is during a crisis when leadership [is most] tested ... whether they have been formally chosen to execute leadership roles, as is normally the case in organizations, or whether [their role] is the result of the natural effects of chance and circumstance.

UK@W: What characteristics and skills do leaders need to have in crisis situations?

Garrido: In adverse conditions and in a context of a crisis such as this one, the leader of a team must, above everything else, validate his [or her] skills, experience and training for the entire team by providing evidence of his skill for assuming leadership beyond his formal authority. After his voice has been validated by his equals, this leader has to demonstrate true "strategic wisdom" by putting it to use for the survival of the group through such skills and abilities as:

The leader needs to analyze ... the scenarios that the team members confront, selecting viable routes for the survival of the entire team of people; and using his or her skills to recognize the strengths and weaknesses of every member of the team. Analytical skill:

He or she needs to demonstrate to the team ... a deep understanding of the reality they are confronted with, so he or she can bring confidence to the team by providing [solutions to problems] ... [such as] rationing or overcoming the natural anguish and uncertainties that emerge within the group. Overcome elementary responses:

The leader searches for collective benefits without drowning ... in perfectionism that could undermine the various contributions of the team. He or she knows that he or she has to devote time [for people] to express themselves in both leisure and work. He or she must provide multidisciplinary tasks that keep the team busy and focused on achievements .... View efforts as a function of goals:

: Even during moments when the team must merely observe his or her decisions ... the leader ... must develop a collaborative team that enables opinions and experience to emerge, along with a stronger sense of intuition. This adds to the leader's flexibility and openness, since expressions of rigidity are not effective during stressful circumstances. Know how to work as a team

: The leader of the team must be capable of showing integrity in his or her decision making, in such a way that he or she preserves the moral coherence of comrades and acts as a behavioral model for them. Ethical coherence and integrity

: Usually, I tell my MBA students that communicating ... motivation and goals to each member of the team is among the most important strategic and leadership skills. That's because developing a working plan and searching for goals of collective interest requires clarity as well as attention to feedback .... Skill at communications

UK@W: Are the skills that are important in handling a crisis similar to those required of a leader in the business world?

Garrido: Clearly. These qualities have been reiterated throughout more than 2,000 years of human history, from the great generals on the battlefield to various teams of people who act under adverse conditions, and to businesses and other modern organizations, where we will certainly be able to apply much of what has been documented [about the miners' experience] in order to motivate people to improve, to overcome obstacles and to work together as a team.

UK@W: What, in your opinion, must be the message that the leader needs to communicate inside the mine?

Garrido: We know that the initial message has been cohesion. In this situation, personal ties and relationships play a fundamental role, along with motivation and keeping the group focused on the goal of the rescue. The leader needs to be able to bring together the collective forces to show a "possible future." He has to be able to explain that the possibility of a potentially successful rescue is close to becoming reality. He needs to convince the group of the need to remain united and act together as a function of that goal. More specifically, this is the essence of that approach: Starting with an idea, explain, communicate and motivate the team to act toward a goal that provides a greater benefit for the entire group. It is vital for the voice of the leader to flow, just as it should be so in today's business world.

In November 2007, participants in a conference of managers at IESE in Barcelona commented that "a strategy that is not communicated is like a beautiful musical score that is not performed." It is worth saying that ideas about a "possible future" have no value if they are not communicated efficiently. In the words of management guru David Norton, "The strategy must be the task of everyone, and the way to achieve it is to let people know what it is and what contribution [they] can provide." This is essential for understanding the tremendous pressures that a leader faces in these circumstances, where 33 people are below ground. The message must be permanent, motivational and sustainable for relationships of mutual survival. In his capacity as a motivator of the team, the leader [in the mine] must balance the following elements of the message that I have described in my book, The Soul of Strategy:

: [Convey] what has happened [in the past], what is happening to us now and what will happen to us in the future. Information

: Being able to accept and discard ideas without reducing participation and motivation. Evaluation

In this type of relationship with people, the leader maintains the message of staying together in a group. Collective survival requires clear leadership that enables everyone to express themselves without encouraging new leaders whose presence would make it easier for people to express views that lead to a breakdown in their goals.

The appropriate communication of roles and status, and of specific hierarchies and functions that each of the miners fulfills in his daily tasks.

The messages [that people listen to] must be specifically targeted at each of the key talents of the organization. In the case of these mining professionals, there has been a clearly hierarchical decision when choosing those who have communicated with the authorities on the surface.

UK@W: Outside the mine, what has to be the message from rescuers and government officials? What is the best way to communicate it? Through a single spokesman? With the participation of the family?

Garrido: The communication [by] technical spokespeople from the government has been consistently appropriate, avoiding [too much] eagerness for a successful rescue [on the one hand] or demoralization and despair [on the other hand], which would send the wrong messages to the 33 people still below the earth. The experience of communicating with the families has been mediated by mining and health authorities who, in the company of a team of national and international experts, have been able to learn the condition of the miners as each message arrived on the surface. This permits people [on the outside] to make the right moves at the right time for [the miners'] mental and physical health. Although the group of people who are buried below the earth have some experience when it comes to the hard mining work that they carry out on a daily basis, they must spend two months under adverse conditions until the promised rescue.

UK@W: Do you believe that there is a parallel between the current case of the 33 Chilean miners and the airplane accident in the Cordillera mountain chain in the Andes in 1972? On that occasion, a Uruguayan airplane bound for Chile blew up with 45 passengers on board. After 72 days in the mountains, only 16 people survived.

Garrido: The similarities can be seen in the extremely difficult conditions that the survivors in that case were forced to face.... I think that in [the miners'] case the possibilities of connecting with the surface that have emerged over the past two weeks have made a great deal of difference. The levels of uncertainty and isolation have [been lessened], not to mention the fact that the [current] group [of miners] has not been forced to suffer the death of any of its members, as was the case with the accident of the Uruguayan airplane.

UK@W: The rescue of the miners could take a very long time. What lessons about survival can we learn from extreme situations such as the 1972 plane crash?

Garrido: The first lesson for the business world is that you need to act with flexibility when it comes to achieving your goals. The sorts of management teams that are most likely to succeed are those composed in a heterogeneous way. Heterogeneity, or the idea of cognitive diversity, increases the probability of creative and diverse impulses. The adaptive flexibility of the team is a necessary condition for achieving the goals of survival -- an essential condition of the strategist and the strategy.

UK@W: What will be the main challenges for organizing the group of miners from within and from the outside?

Garrido: We have already mentioned that the motivation of the group, just as in the business world, is essential for maintaining hope for a [rescue.]

The challenge will be to maintain an ordered mind, with a sense of orientation to achievement; the spirit of the body and coherence for fulfilling the goal. [That] effort that must be reiterated and experienced, case by case, by focusing on possible instances of depression that have been detected by reading the behavior of some miners. At any moment, the team on the surface must be able to evaluate potential health conditions among the miners, both mental and physical, as well as foresee and improve [the group's] behavior despite its isolated condition, while also focusing on the complex task of rescuing [the miners]. The team in charge of the rescue must also be concerned with emotionally restraining the families; preparing conditions for the miners to get out [of the mine] and foreseeing conditions that people will face after they leave [the mine], when they will surely go from being in a condition of forced isolation to one of extreme exposure to the public.

UK@W: The experiences of people who survive extreme situations often serve as case studies for students in business schools around the world. What lessons can be learned in the business world from the experience of the 33 trapped miners?

Garrido: The main lesson in this case can be summed up without doubt by the way they have overcome the crisis. There are lessons here that transcend the world of business instruction when it comes to [defining] such expressions as "decision making," "leadership" and "teamwork." Clearly, the implementation of a plan requires someone who assumes risks. We know that both the plans we make and the risks that we assume ultimately lead us to make the necessary decisions.

This is precisely where I believe there emerges a ... lesson for those who deal with teams of human beings on a daily basis. For example, in the business world, you often have to battle against adverse conditions. Strategy without decision-making is the equivalent of decision-making without action; ultimately, it is useless. A leader can choose the route of not taking action toward an achievement or ... he can act in search of the goal. The decision-making of a leader or strategist depends on his capacity for thinking about and sensing a central goal on a regular basis.... It is not very different from what we know in the world of business strategy and management about decision-making.... Without any doubt, [the miners] have given us some major lessons about management from 700 meters below the earth.

Published: July 03, 2012 in Knowledge@Wharton

Jeffrey S. Ashby is a former NASA space shuttle commander, the typical hero-type astronaut -- ex-Top Gun former Navy pilot, combat missions in the Middle East, three Space Shuttle missions. John Kanengieter is cut from that same cloth, but more earth-bound. He is director of leadership at the National Outdoor Leadership School -- climbing mountains, leading expeditions, following the adventure path. Stephen Girsky is vice chairman of GM with overall responsibility for corporate strategy, business alliances, new business development and other areas, and also holds the title of chairman of the Adam Opel AG Supervisory Board.

All three spoke at the recent 16th Annual Wharton Leadership Conference -- sponsored by Wharton's Center for Leadership and Change Management and Center for Human Resources -- whose theme was "Leading in a World of Conflict."

In an interview that same day, Girsky spoke with Wharton management professor John Paul MacDuffie about GM's renewed emphasis on the customer even as it faces such challenges as industry-wide overcapacity, strong competition from rivals both in the U.S. and Europe, and slower-than-expected sales of the Chevy Volt. Click here for that interview in both print and audio format.

Meanwhile, Ashby and Kanengieter offered leadership lessons that they noted apply not only to their outsized adventure worlds, but also to the boardroom and conference tables of the more conventional business community. Essentially, Ashby and Kanengieter said, it comes down to preparation, a single-minded focus on the goal and a team of what they called "active followers."

Each of the men made their points by talking about key moments in their respective careers. In Ashby's case, it was commanding an International Space Station docking-and-repair mission -- number 112, on the Atlantis in October 2002. For Kanengieter, it was his part in an Indian/American attempt to scale Panwali Dwar -- at 21,000-plus feet, one of the tallest and most difficult mountains to climb in the Indian portion of the Himalayas.

Cold MountainAshby began his saga by noting that NASA puts together its most important crews -- those who take on Space Shuttle missions -- in a way that would seem unconventional in a normal corporate setting. Approximately nine months before Mission 112 was to take off, Ashby received an 11 p.m. call from NASA headquarters congratulating him on being named Mission commander. But headquarters also told him that it had already picked his crew -- i.e., he would have no say in who would be on that crew, and yet he would be expected to make sure everyone worked well together and completed the mission successfully.

In the early days of NASA space missions, Ashby said, the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo astronauts were assumed to be leaders. "They were all military pilots, and all had military leadership training." By the 1990s, the commanders were still military, but "it was a different kind of setting with the International Space Station." Now, instead of all military people, there were scientists and other mission specialists who were important -- and not necessarily motivated by military-type leadership. There needed to be a different way to mold the six or seven crew members -- each one of them responsible for delicate and complex tasks -- into a cohesive unit.

That is where Ashby said his path crossed with Kanengieter and the National Outdoor Leadership School. He decided to take his diverse crew --- one woman, a Russian who spoke no English, his pilot and a medical doctor among them -- to the Canyonlands of Utah for an 11-day wilderness trek, the same length as their future Space Shuttle mission.

Ashby intended to make it as arduous and challenging as possible. He knew that seven days together on a mission was just about the limit before breakdowns -- arguments, resentments and the like -- would occur. In addition, he took the crew to Utah's mountains in November, just as it was getting cold and damp. Each day, he changed leaders -- the mission was to traverse a set of canyons and mountains across the National Park -- so everyone would get a chance to be at the head and also in the "active following" positions.

At one point, near a passage filled with cascading water, the group was strung out so that those in front could not see or hear those in back. One of those in the back suggested returning the way they had come and circling around -- taking the longer, but safer, route. He was eventually overruled, and the group decided to slog through the rushing water to the more direct route.

What was key for Ashby, though, was that the overruled crew member -- instead of sulking or arguing -- volunteered to be the person who would lift and guide everyone through the most dangerous part of the rock wall where the water was rushing down. "He disagreed, and yet he gave his full commitment," noted Ashby. "I knew then that we would be a team and we would make it. Even [though there was] disagreement, it set the tone for the trip -- and later the mission. The behavior was [defined by a sense of] respect and cooperation."

According to Ashby, these qualities were especially important once the mission began. The most crucial part would be docking with the repair materials for the International Space Station. It is a two-day trek from take-off to docking -- an almost incomprehensible piece of precision, hooking together 240 miles up at 18,000 miles per hour.

Everything was fine until about three miles away and three minutes out when it suddenly became apparent from computer readouts that a calculation was wrong. "You only get one shot at docking, because that is all the fuel you have in the thrusters," said Ashby. It was not that they faced a death-defying situation, he added. Nevertheless, aborting a billion-dollar mission because of a miscalculation was not what leadership was about. For several minutes, Ashby went back and forth with his crew, trying to figure out what was wrong with the readout, the computers, the mission itself. Finally, the word came from Houston, with about a minute to go: "Do what you think is right."

"What do you want from a leader then?" Ashby asked. Everything comes "down to a moment." Right about then, he added, everything they had worked for -- from that trek in the Canyonlands to the trust they had given each other -- came to the fore. One crew member flashed through the readouts; another put his use of radar to the test, and all stated that they had confidence in Ashby's decision-making. In the end, rather than depend on mere computers, Ashby led the pilot manually, to the point of looking out the window like a parent instructing his teenager to drive. The mission was saved.

Trapped by AvalanchesKanengieter's mountain climb was not a billion-dollar effort, but it would be high up on the mountaineering scale since only one team had ever scaled Panwali Dwar before. It had taken a month to establish three base camps at various altitudes. The team finally made it to the third camp at 18,000 feet.

Then a series of snowstorms, creating several avalanches, trapped the team for several days. There was only so much time they could spend in the rare air and freezing cold of 18,000 feet. But on the last possible day, a clearing came, and Kanengieter and the team leader set out to rappel the last leg of the journey.

Minutes after they were lined up by rope, about 150 feet up-and-down from one another, they heard a cracking sound. The snow that had come down from the avalanches was fissuring, caused by an air pocket below. About 15 feet ahead of the leader, the ice was starting to fracture. "My life was hanging by a thread, but which way should we go -- up or down?" said Kanengieter. In this case, each of the people had significant knowledge about mountain climbing, but the point was to make a decision. The leader wanted to go on, but Kanengieter -- intuiting that the fracture would, at best, thwart the route to the top and, at worst, cause an avalanche that would kill the men -- overruled him.

"I was a follower there -- an active follower -- and my job was to figure out how to help support the leader to make a critical decision," said Kanengieter, who noted that he could see better from below the real danger they were in. "Our leadership model leverages the strength of active followers, which is highly effective during uncertainty and times of conflicting options." Though the mission had to be aborted and the goal was never reached, the leader and the rest of the team members respected Kanengieter's knowledge and former leadership skills.

As Ashby and Kanengieter noted, leadership is not one-dimensional and autocratic. Yes, the leader has to make the final decision, but not without real input, which cannot be given by team members unless they are empowered all along the way by the leader. It is this concept of the active follower that Ashby and Kanengieter claim is essential. They gain it by trust, a focus on the goal and proper communication, not just at the crisis moment, but from the first day of the team's selection. Even if the goal, as in the mountain climb, has to be abandoned, the entire group buys in.

"It works in mountaineering, in space and in the business world," said Ashby. "Everyone considers me to be a leader only after I give them the power to be active followers. They can challenge my decision, but they support my leadership once we make that decision, and then they support every member of the team enthusiastically."

Published: May 03, 2012 in Knowledge@Wharton

The second segment of Knowledge@Wharton's interview with Google's Chade-Meng Tan, best-selling author of Search Inside Yourself, focuses on the role that emotional intelligence can play in helping managers resolve conflicts within high performance teams. It also shows how the Google SIY program, through compassion training, has helped managers become more successful and even more charismatic.

To read more, check out the first part of the interview, Google's Chade-Meng Tan Wants You to Search Inside Yourself for Inner (and World) Peace and the third, How Emotional Intelligence Helps the Bottom Line.Knowledge@Wharton: How has the Search Inside Yourself (SIY) program helped Google employees deal with issues such as having difficult conversations? For example, has it helped resolve conflicts that might emerge in high-performance teams whose members might be passionate about their work but find it hard to get along?

Meng: There's one situation where this happens a lot -- and for understandable reasons. Google has product engineers whose job is to build features for our products. We also have production engineers who are responsible for making sure that Google doesn't break. As you can imagine, the people who build features tend to be very aggressive; that makes sense because they want to create new features to benefit our users. They're always thinking, "Let's create as many features as we can." In contrast, production engineers are very conservative, and again, for very good reasons. They care about Google not breaking; if Google breaks, nobody benefits. So, even though on both sides there are very smart people who want to do the right thing, you find them in conflict. If you are not careful and if this persists for a long time, you get a tendency, whichever side you're on, to think, "The other guys are trying to screw with me." Then it becomes personal because it's about me. "They hate me. They're screwing with me."

I had a person in my class who felt this way. He was one of those over-achievers and always performed very well, but he had a lot of problems with the other side. After going through SIY, he realized that the person on the other side was not trying to screw with him. I mean, no one wakes up in the morning and says, "I'm going to screw with Jim. That's what I'm going to do for the rest of my day." He also realized that if he were in the other person's shoes, he would be saying exactly the same things -- because he, too, would be trying to do the right thing. Once he figured that out, he learned how to discern the story from reality. He realized that the belief that the other guy's trying to screw with me -- that's a story. The reality was different. Once he figured that out, the whole work relationship changed and then everything worked more smoothly.

That's a good example of how emotional intelligence resolves conflicts that lead to higher performance. That is, in fact, one of the best-selling points of emotional intelligence -- it reduces friction. If people have high emotional intelligence, they have less friction. And if there's less friction -- I mean, from a system point of view -- you lose less energy and get more done.

Knowledge@Wharton: How has cultivating compassion through meditation helped Google employees hone their leadership skills?

Meng: This has happened in a couple of ways -- some are visible and others are less visible. What is most visible to me is charisma. When employees took the SIY course and worked on their compassionate practices, their charisma seemed to increase -- and later I realized how. My friend Olivia Fox Cabane, who wrote the book, The Charisma Myth, taught that charisma has three components: Presence, confidence or power and warmth. Presence means when you're talking to somebody and interacting with them, you are there, your full attention and energy are on that person and the other person perceives you as caring for him or her. That helps in your charisma. The other things that really help are your confidence and warmth. If you have all three, the other person perceives you as being very charismatic.

The most charismatic leaders I have met are Bill Clinton, Barack Obama and the Dalai Lama. All three of them are strong in these three factors. Now, let's take these three factors and compare them with compassion. Presence is part of the compassion training. Concentrating attention through mindfulness is the basic training that leads to compassion. So, if you training people to nurture compassion, you are already training them to develop presence.

Now let's take confidence. I've found that compassion training has been very helpful in creating confidence. This is a bit counterintuitive, but here's why. I discovered this within myself. I went through a compassion exercise and discovered immediately the first time I did the exercise, that confidence increased substantially. Over time, I discovered it was permanent, which is fascinating. Do five minutes of exercise and you have a permanent increase in confidence. And why is that so? I realized that part of what's holding me back from self-confidence is fear of suffering. In practicing compassion, you create the ability to identify with and relieve other people's suffering. Once you do that, once you find that you can experience other people's suffering, that reduces your own fear of suffering, and it increases your confidence. That is how compassion creates confidence. As for warmth, that's very obvious. Compassionate people are very warm. So, by cultivating compassion, the first effect is your charisma will increase. That's the visible part.

There's another important leadership quality, but it is less visible. This quality is level-five leadership as defined by Jim Collins in his book Good to Great. Collins defines level-five leadership as the most effective form of leadership. Level five leaders have two important qualities, which seem to be paradoxical. These leaders are very ambitious, and at the same time, they are personally very humble. Their ambition is for the greater good, which is why they don't feel the need to glorify themselves and they're personally humble at the same time.

Now, if you tease out the components of compassion, there are three of them. The first is the affective component, which is "I care about you." There's the cognitive component compassion, which is "I understand you" or "I want to understand you." And then there's the motivational component, which is "I want to help you." Now, if you superimpose the three compassion components with the two level-five leadership qualities, you find that that the first two components of compassion -- the affective and the cognitive elements -- they increase personal humility. The motivational component of compassion increases your ambition for the greater good. That's why it is obvious that compassion training is necessary for organizations that want to build level five leadership. That is the theory.

In practice, at Google, I don't see that it's very visible and the reason is because it's already widespread. We tend to hire the type of people who are very, very smart and very ambitious to want to change the world, but personally, quite humble. So they're already halfway there or 75% there. That's why the training did not create an impact that's visible to me.

There's one other thing, and it's not about compassion alone. The entire SIY training, with compassion playing the biggest part, has helped some people become better managers. I have an example. One manager, after compassion training, discovered that he needed to do something for his people. He asked his people, "What am I doing for you that creates the most value for you? And what am I doing that creates no value?" Through their answers, he found the ability to work less and get more done. For example, he realized it didn't create any value for his team if he read every e-mail that came in. The team said, "We don't need you to read every e-mail. All we need is for you to solve the problems we cannot solve. That's where your value is." When he learned that, he began to spend less time on stuff that did not matter. And whatever stuff he worked on, it created more value. After a while, his team kept getting bigger and he found he had a lot of free time. In his case, compassion -- because it gave him the incentive to step back and think, "What more can I do for my people?" -- helped him become a better manager, and, of course, he got a promotion.

Knowledge@Wharton: In principle, everyone agrees that kindness and compassion are good qualities. But very often in business they are viewed as weaknesses. Kind managers are seen as being weak, soft or at least tolerant of failure, which de-motivates high performers. Such managers are accused of being "too nice." In contrast, so-called "tough managers" who bully or browbeat their subordinates are seen as star performers who know how to crack the whip and get the job done. Did you face such issues at Google? If so, how did you make the link between a program that aims at cultivating attentiveness and kindness and the company's performance and profit goals?

Meng: I want to challenge the premise of this question. I think it is possible to be tough and to be kind and compassionate at the same time. The two are not mutually exclusive.

I can think of two examples. The first example is of two guys named Bill and Dave. Their last names are Hewlett and Packard. They started this company called HP in 1939, if I remember correctly. In the early 1940s the had an idea that was radical for its time. They said, "Let's treat our employees nicely, let's be fair to them, let's reward them well, let's listen to their opinions." Back then, people must have thought, "What are these guys smoking? This is the craziest thing we've ever heard. If you're not tough on your people, how do you get them to do stuff?" But it turns out that they were right. Now when we fast-forward and look back, it's something we take for granted at least in a tech company. We say, "Of course we treat our people well. Of course we respect them. How else do we get them to do good work?" But the point is, back in their time, Bill and Dave might have been considered the type of people whom we would criticize today as being too nice, soft and weak. But it turns out they were not softies at all. Dave Packard, for example, had the reputation that he would fire people in person. If any manager at HP crossed an ethical line, Dave personally would fly over to the site and fire that guy. He was no softie. Bill and Dave personified a combination of being tough and being nice. They had a very successful company for many, many years.

The second example is what we talked about earlier -- naval officers. The nicest naval officers are the most effective, and nobody accuses them of being soft. You can be as tough as nails as well as kind and compassionate. If you do both at the same time, you can do amazing work. If you have to choose one or the other, it reflects a lack of skillfulness in managing.

The problem with just being tough, when you browbeat and bully people, is that you create at least three costs. The first is long-term sustainability. When people don't like working for you, they work only because they have to and if they can leave, they will. You're going to have a retention issue. Even if you do retain people, you are going to have a sustainability issue because they will not work very hard for very long. That is the visible cost.

Other costs are less visible. They are quality and commitment. If people are not happy, they're not going to commit. If they're not going to commit, quality is going to suffer. This may be reflected in poor quality of customer service. If your people are not happy, they're not going to treat customers well and you're going to lose your customers. Then you're going to have to spend a lot of money on "marketing." But if you treat your customers well, you won't lose them in the first place and you won't have to spend that much on marketing.

There's a third aspect, which is even less visible. It impacts companies like Google, which rely on creativity. If all your managers do is bully, your people are less likely to be creative problem solvers. Then you lose a lot of creative energy. I have pondered on why this is so widespread. Why are there so many managers who only know how to bully? I think it's because the short-term gain of bullying is very visible. In the next quarter, if you bully your people, you're going to get higher numbers. What is lost is in the long-term and it's not very visible. For example, what I just said about the opportunity cost of losing commitment, quality and creativity, you don't see them easily. So, if you're an unskilled manager, if all you can see are short-term gains, then you tend to reward bullies because the good things that you lose -- the opportunity costs -- are invisible to you. The biggest opportunity cost, if you only have managers who drive performance through bullying, is that you never go from good to great. Your company will always be average. Average is not bad, right? You may pay dividends every so often, but you'll only be average.