Global Gender Gap Report 2023

The Global Gender Gap Index annually benchmarks the current state and evolution of gender parity across four key dimensions (Economic Participation and Opportunity, Educational Attainment, Health and Survival, and Political Empowerment). It is the longest-standing index tracking the progress of numerous countries’ efforts towards closing these gaps over time since its inception in 2006.

INSIGHT REPORT JUNE 2023

June 2023 Global Gender Gap Report 2023 Terms of use and disclaimer The analysis presented in the Global Gender The World Economic Forum in no way represents Gap Report 2023 (herein: “Report”) is based on or warrants that it owns or controls all rights in all a methodology integrating the latest statistics Data, and the World Economic Forum will not be from international organizations and a survey of liable to users for any claims brought against users executives. by third parties in connection with their use of any Data. The World Economic Forum, its agents, The 昀椀ndings, interpretations and conclusions of昀椀cers and employees do not endorse or in any expressed in this work do not necessarily re昀氀ect the respect warrant any third-party products or services views of the World Economic Forum. The Report by virtue of any Data, material or content referred to presents information and data that were compiled or included in this Report. Users shall not infringe and/or collected by the World Economic Forum upon the integrity of the Data and in particular (all information and data referred herein as “Data”). shall refrain from any act of alteration of the Data Data in this Report is subject to change without that intentionally affects its nature or accuracy. If notice. The terms country and nation as used in the Data is materially transformed by the user, this this Report do not in all cases refer to a territorial must be stated explicitly along with the required entity that is a state as understood by international source citation. For Data compiled by parties other law and practice. The terms cover well-de昀椀ned, than the World Economic Forum, users must geographically self-contained economic areas that refer to these parties’ terms of use, in particular may not be states but for which statistical data are concerning the attribution, distribution, and maintained on a separate and independent basis. reproduction of the Data. When Data for which the World Economic Forum is the source (herein “World Although the World Economic Forum takes every Economic Forum”), is distributed or reproduced, reasonable step to ensure that the Data thus it must appear accurately and be attributed to the compiled and/or collected is accurately re昀氀ected World Economic Forum. This source attribution in this Report, the World Economic Forum, its requirement is attached to any use of Data, whether agents, of昀椀cers and employees: (i) provide the Data obtained directly from the World Economic Forum “as is, as available” and without warranty of any or from a user. Users who make World Economic kind, either express or implied, including, without Forum Data available to other users through any limitation, warranties of merchantability, 昀椀tness for a type of distribution or download environment agree particular purpose and non-infringement; (ii) make to make reasonable efforts to communicate and no representations, express or implied, as to the promote compliance by their end users with these accuracy of the Data contained in this Report or terms. its suitability for any particular purpose; (iii) accept no liability for any use of the said Data or reliance Users who intend to sell World Economic Forum placed on it, in particular, for any interpretation, Data as part of a database or as a stand-alone decisions, or actions based on the Data in this product must 昀椀rst obtain the permission from the Report. Other parties may have ownership interests World Economic Forum ([email protected]). in some of the Data contained in this Report. World Economic Forum All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, 91-93 route de la Capite or transmitted, in any form or by any means, CH-1223 Cologny/Geneva electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise Switzerland without the prior permission of the World Economic Tel.: +41 (0)22 869 1212 Forum. Fax: +41 (0)22 786 2744 E-mail: [email protected] ISBN-13: 978-2-940631-97-1 www.weforum.org The report and an interactive data platform are Copyright © 2022 available at http://reports.weforum.org/global- by the World Economic Forum gender-gap-report-2023. First part of the title: Second part of the title 2

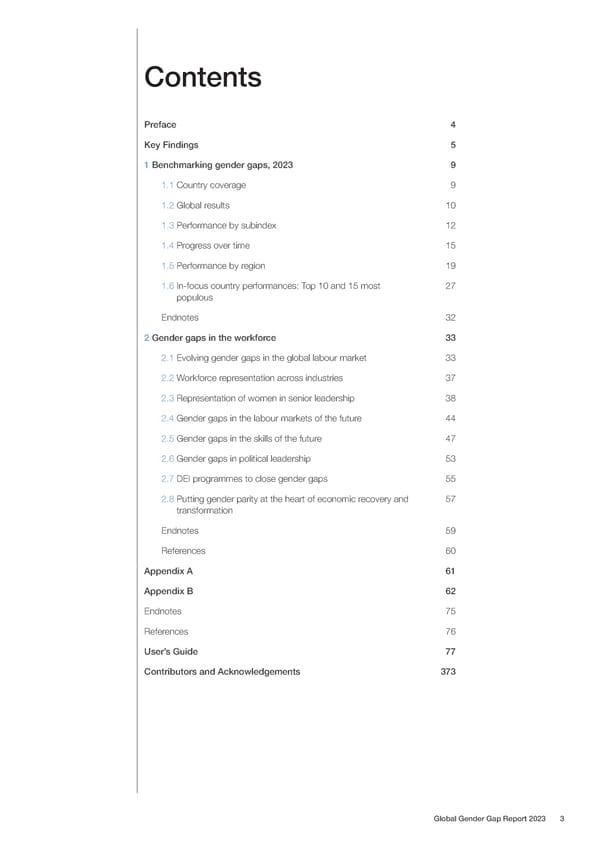

Contents Preface 4 Key Findings 5 1 Benchmarking gender gaps, 2023 9 1.1 Country coverage 9 1.2 Global results 10 1.3 Performance by subindex 12 1.4 Progress over time 15 1.5 Performance by region 19 1.6 In-focus country performances: Top 10 and 15 most 27 populous Endnotes 32 2 Gender gaps in the workforce 33 2.1 Evolving gender gaps in the global labour market 33 2.2 Workforce representation across industries 37 2.3 Representation of women in senior leadership 38 2.4 Gender gaps in the labour markets of the future 44 2.5 Gender gaps in the skills of the future 47 2.6 Gender gaps in political leadership 53 2.7 DEI programmes to close gender gaps 55 2.8 Putting gender parity at the heart of economic recovery and 57 transformation Endnotes 59 References 60 Appendix A 61 Appendix B 62 Endnotes 75 References 76 User’s Guide 77 Contributors and Acknowledgements 373 Global Gender Gap Report 2023 3

June 2023 Global Gender Gap Report 2023 Preface Saadia Zahidi Managing Director Recent years have been marked by major between participating countries and a wider setbacks for gender parity globally, with previous network of leaders. Focusing on corporate action, progress disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic’s the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) Lighthouse impact on women and girls in education and the Programme brings together a cross-industry group workforce, followed by economic and geopolitical of organizations taking action to drive better and crises. Today, some parts of the world are seeing faster DEI outcomes through CEO leadership, and partial recoveries while others are experiencing knowledge-sharing on initiatives that have achieved deteriorations as new crises unfold. Global gender signi昀椀cant, quanti昀椀able and sustained impact for gaps in health and education have narrowed underrepresented groups. over the past year, yet progress on political empowerment is effectively at a standstill, and This year’s edition of the Global Gender Gap women’s economic participation has regressed Report also analyses new data on labour market rather than recovered. outcomes for women, at both the macro-economic and industry level. We are grateful to LinkedIn The tepid progress on persistently large gaps and Coursera for their continued collaboration in documented in this seventeenth edition of the providing unique data and new measures to track Global Gender Gap Report creates an urgent case gender gaps in workforce participation, senior for renewed and concerted action. Accelerating leadership and online skilling. We also thank the progress towards gender parity will not only members of the Centre for the New Economy and improve outcomes for women and girls but bene昀椀t Society Advisory Board for their leadership, the over economies and societies more widely, reviving 150 partners of the Centre, and the Global Future growth, boosting innovation and increasing Council on the Future of the Care Economy and resilience. The report provides a tool for consistent Community of Chief Diversity and Inclusion Of昀椀cers tracking of gender gaps across the economic, for expert guidance, as well as a network of national political, health and education spheres, and is ministries of economy, education and labour for designed for leaders to identify areas for individual their commitment to advancing gender parity. and collective action. We would like to express our gratitude to Silja At the World Economic Forum, the Centre for Baller, Kusum Kali Pal, Kim Piaget and Ricky Li the New Economy and Society complements for their leadership of this project. We would also measurement of gender gaps with a set of initiatives like to thank our colleagues Attilio Di Battista, Eoin and coalitions dedicated to advancing progress. O’Cathasaigh, Gulipairi Maimaiti and Mark Rayner The Gender Parity Accelerators are working for their support. towards gender parity in economic participation – scaling policies and strategies to improve women’s We hope the data and analysis provided in this representation in the workforce and in leadership report can further accelerate the speed of travel – as well as pay equity. Accelerators are currently towards parity by catalysing and informing action present in 14 countries in Latin America and the by public- and private-sector leaders in their Caribbean, the Middle East and North Africa, efforts to close the global gender gap. With the Central Asia, East Asia and the Paci昀椀c, and Sub- myriad challenges the world faces, we need the full Saharan Africa. The Global Learning Network linked power of human creativity and collaboration to 昀椀nd to the Accelerators surfaces successful policies pathways to shared prosperity. and practices and promotes knowledge exchange Global Gender Gap Report 2023 4

June 2023 Global Gender Gap Report 2023 Key Findings The Global Gender Gap Index annually benchmarks levels, the overall rate of change has slowed down the current state and evolution of gender parity signi昀椀cantly. Even reverting back to the time horizon across four key dimensions (Economic Participation of 100 years to parity projected in the 2020 edition and Opportunity, Educational Attainment, Health would require a signi昀椀cant acceleration of progress. and Survival, and Political Empowerment). It is the longest-standing index tracking the progress of – According to the 2023 Global Gender Gap numerous countries’ efforts towards closing these Index no country has yet achieved full gender gaps over time, since its inception in 2006. parity, although the top nine countries (Iceland, Norway, Finland, New Zealand, Sweden, This year, the 17th edition of the Global Gender Germany, Nicaragua, Namibia and Lithuania) Gap Index benchmarks gender parity across 146 have closed at least 80% of their gap. For the countries, providing a basis for robust cross- 14th year running, Iceland (91.2%) takes the top country analysis. Further, examining a subset of 102 position. It also continues to be the only country countries that have been included in every edition to have closed more than 90% of its gender of the index since 2006 provides a large constant gap. sample for time-series analysis. The Global Gender Gap Index measures scores on a 0 to 100 scale – The global top 昀椀ve is completed by three other and scores can be interpreted as the distance Nordic countries – Norway (87.9%, 2nd), covered towards parity (i.e. the percentage of the Finland (86.3%, 3rd) and Sweden (81.5%, gender gap that has been closed). Cross-country 5th) – with one country from East Asia and the comparisons support the identi昀椀cation of the most Paci昀椀c – New Zealand (85.6%, 4th) – ranked effective policies to close gender gaps. 4th. Additionally, from Europe, Germany (81.5%) moves up to 6th place (from 10th), Lithuania Key 昀椀ndings include the index results in 2023, trend (80.0.%) returns to the top 10 economies, analysis of the trajectory towards parity and data taking 9th place, and Belgium (79.6%) joins deep dives through new metrics partnerships and the top 10 for the 昀椀rst time in 10th place. One contextual data. country from Latin America (Nicaragua, 81.1%) and one from Sub-Saharan Africa (Namibia, 80.2%) – complete this year’s top 10, taking Global results and time to parity the 7th and 8th positions, respectively. The two countries that drop out of the top 10 in 2023 are Ireland (79.5%,11th, down from 9th in 2022) The global gender gap score in 2023 for all 146 and Rwanda (79.4%, 12th, down from 6th). countries included in this edition stands at 68.4% closed. Considering the constant sample of 145 – For the 146 countries covered in the 2023 countries covered in both the 2022 and 2023 index, the Health and Survival gender gap has editions, the overall score changed from 68.1% to closed by 96%, the Educational Attainment 68.4%, an improvement of 0.3 percentage points gap by 95.2%, Economic Participation and compared to last year’s edition. Opportunity gap by 60.1%, and Political Empowerment gap by 22.1%. When considering the 102 countries covered continuously from 2006 to 2023, the gap is 68.6% – Based on the constant sample of 102 countries closed in 2023, recovering to the level reported covered in all editions since 2006, there is in the 2020 edition and advancing by a modest an advancement from 95.3% to 96.1% on 4.1 percentage points since the 昀椀rst edition of the Educational Attainment between 2022 and report in 2006. At the current rate of progress, it 2023, moving beyond pre-pandemic levels, will take 131 years to reach full parity. While the and an improvement from 95.7% to 95.9% for global parity score has recovered to pre-pandemic the Health and Survival dimension. The Political Global Gender Gap Report 2023 5

Empowerment score edges up from 22.4% progress, Latin America and the Caribbean will to 22.5% and Economic Participation and take 53 years to attain full gender parity. Opportunity regresses from 60.0% in 2022 to 59.8% in 2023. – At 69% parity, Eurasia and Central Asia ranks 4th out of the eight regions on the overall – At the current rate of progress over the 2006- Gender Gap Index. Based on the aggregated 2023 span, it will take 162 years to close the scores of the constant sample of countries Political Empowerment gender gap, 169 years included since 2006, the parity score since the for the Economic Participation and Opportunity 2020 edition has stagnated, although there has gender gap, and 16 years for the Educational been an improvement of 3.2 percentage points Attainment gender gap. The time to close since 2006. Moldova, Belarus and Armenia the Health and Survival gender gap remains are the highest-ranking countries in the region, unde昀椀ned. while Azerbaijan, Tajikistan and Türkiye rank the lowest. The difference in parity between Regional results and time to the highest and the lowest ranked country is parity 14.9 percentage points. At the current rate of progress, it will take 167 years for the Eurasia and Central Asia region to reach gender parity. Gender parity in Europe (76.3%) surpasses the parity level in North America (75%) this year to rank – East Asia and the Paci昀椀c is at 68.8% parity, 昀椀rst of eight geographic regions. Closely behind marking the 昀椀fth-highest score out of the eight Europe and North America is Latin America and the regions. Progress towards parity has been Caribbean, with 74.3% parity. Trailing more than stagnating for over a decade and the region 5 percentage points behind Latin America and the registers a 0.2 percentage-point decline since Caribbean are Eurasia and Central Asia (69%) as the last edition. New Zealand, the Philippines well as East Asia and the Paci昀椀c (68.8%). Sub- and Australia have the highest parity at the Saharan Africa ranks 6th (68.2%), slightly below the regional level, with Australia and New Zealand global weighted average score (68.3%). Southern also being the two most-improved economies Asia (63.4%) overtakes the Middle East and North in the region. On the other hand, Fiji, Myanmar Africa (62.6%), which is, in 2023, the region furthest and Japan are at the bottom of the list, with away from parity. Fiji, Myanmar and Timor-Leste registering the largest declines. At the current rate of progress, – Across all subindexes, Europe has the highest it will take 189 years for the region to reach gender parity of all regions at 76.3%, with gender parity. one-third of countries in the region ranking in the top 20 and 20 out of 36 countries with at – Sub-Saharan Africa’s parity score is the sixth- least 75% parity. Iceland, Norway and Finland highest among the eight regions at 68.2%, are the best-performing countries, both in the ranking above Southern Asia and the Middle region and in the world, while Hungary, Czech East and North Africa. Progress in the region Republic and Cyprus rank at the bottom of has been uneven. Namibia, Rwanda and South the region. Overall, there is a decline of 0.2 Africa, along with 13 other countries, have percentage points in the regional score based closed more than 70% of the overall gender on the constant sample of countries. At the gap. The Democratic Republic of the Congo, current rate of progress, Europe is projected to Mali and Chad are the lowest-performing attain gender parity in 67 years. countries, with scores below 62%. Based on the constant sample, this marks a marginal – Just behind Europe, North America ranks improvement of 0.1 percentage points. At the second, having closed 75% of the gap, which is current rate of progress, it will take 102 years to 1.9 percentage points lower than the previous close the gender gap in Sub-Saharan Africa. edition. While Canada has registered a 0.2 percentage-point decline in the overall parity – Southern Asia has achieved 63.4% gender score since the last edition, the United States parity, the second-lowest score of the eight has seen a reduction of 2.1 percentage points. regions. The score has risen by 1.1 percentage At the current rate of progress, 95 years will be points since the last edition on the basis of the needed to close the gender gap for the region. constant sample of countries covered since 2006, which can be partially attributed to the – With incremental progress towards gender rise in scores of populous countries such as parity since 2017, Latin America and the India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Along with Caribbean has bridged 74.3% of its overall Bhutan, these are the countries in Southern gender gap, a 1.7 percentage-point increase Asia that have seen an improvement of 0.5 in overall gender parity since last year. After percentage points or more in their scores since Europe and North America, the region has the the last edition. Bangladesh, Bhutan and Sri third-highest level of parity. Nicaragua, Costa Lanka are the best-performing countries in the Rica and Jamaica register the highest parity region, while Pakistan, Iran and Afghanistan are scores in this region and Belize, Paraguay and at the bottom of both the regional and global Guatemala the lowest. At the current rate of ranking tables. At the current rate of progress, Global Gender Gap Report 2023 6

full parity in the region will be achieved in 149 nearly 10 percentage points lower. Women’s years. representation drops to 25% in C-suite positions on average, which is just more than half of the – In comparison to other regions, the Middle representation in entry-level positions, at 46%. East and North Africa remains the furthest Different industries display different intensities away from parity, with a 62.6% parity score. and patterns when it comes to this “drop This is a 0.9 percentage-point decline in parity to the top”. Women fare relatively better in since the last edition for this region, based on industries such as Consumer Services, Retail, the constant sample of countries covered since and Education, which register ratios of C-suite 2006. The United Arab Emirates, Israel and vs entry level representation between 64% and Bahrain have achieved the highest parity in the 68%. Construction, Financial Services, and region, while Morocco, Oman and Algeria rank Real Estate present the toughest conditions for the lowest. The region’s three most populous aspiring female leaders, with a ratio of C-suite to countries – Egypt, Algeria and Morocco – entry-level representation of less than 50%. For register declines in their parity scores since the the past eight years, the proportion of women last edition. At the current rate of progress, full hired into leadership positions has been steadily regional parity will be attained in 152 years. increasing by about 1% per year globally. However, this trend shows a clear reversal Evolving gender gaps in the starting in 2022, which brings the 2023 rate global labour market back to 2021 levels. – Gender gaps in the labour markets of the The state of gender parity in the labour market future: Science, technology, engineering remains a major challenge. Not only has women’s and mathematics (STEM) occupations are an participation in the labour market globally slipped important set of jobs that are well remunerated in recent years, but other markers of economic and expected to grow in signi昀椀cance and scope opportunity have been showing substantive in the future. Linkedin data on members’ job disparities between women and men. While women pro昀椀les show that women remain signi昀椀cantly have (re-)entered the labour force at higher rates underrepresented in the STEM workforce. than men globally, leading to a small recovery in Women make up almost half (49.3%) of total gender parity in the labour-force participation rate employment across non-STEM occupations, since the 2022 edition, gaps remain wide overall but just 29.2% of all STEM workers. While the and are apparent in several speci昀椀c dimensions. percentage of female STEM graduates entering into STEM employment is increasing with every – Evolving gender gaps in the global labour cohort, the numbers on the integration of STEM market: Women have been (re-)entering the university graduates into the labour market workforce at a slightly higher rate than men, show that the retention of women in STEM even resulting in a modest recovery from last year’s one year after graduating sees a signi昀椀cant low. Between the 2022 and 2023 edition, parity drop. Women currently account for 29.4% of in the labour-force participation rate increased entry-level workers; yet for high-level leadership from 63% to 64%. However, the recovery in roles such as VP and C-suite, representation women’s labour-force participation remains drops to 17.8% and 12.4%, respectively. When un昀椀nished, as parity is still at the second-lowest it comes to arti昀椀cial intelligence (AI) speci昀椀cally, point since the 昀椀rst edition of the index in 2006 talent availability overall has surged, increasing and signi昀椀cantly below its 2009 peak of 69%. six times between 2016 and 2022, yet female Compounding these patterns, women continue representation in AI is progressing very slowly. to face higher unemployment rates than men, The percentage of women working in AI today with a global unemployment rate at around is approximately 30%, roughly 4 percentage 4.5% for women and 4.3% for men. Even when points higher than it was in 2016. women secure employment, they often face substandard working conditions: a signi昀椀cant – Gender gaps in the skills of the future: portion of the recovery in employment since Online learning offers 昀氀exibility, accessibility 2020 can be attributed to informal employment, and customization, enabling learners to whereby out of every 昀椀ve jobs created for acquire knowledge in a manner that suits women, four are within the informal economy; their speci昀椀c needs and circumstances. for men, the ratio is two out of every three jobs. However, women and men currently do not have equal opportunties and access to – Workforce representation across industries: these online platforms, given the persistent Global data provided by LinkedIn shows digital divide. Even when they do use these persistent skewing in women’s representation platforms, there are gender gaps in skilling, in the workforce and leadership across especially those skills that are projected to industries. In LinkedIn’s sample, which covers grow in importance and demand. Data from 163 countries, women account for 41.9% of Coursera suggests that as of 2022, except the workforce in 2023, yet the share of women for teaching and mentoring courses, there is in senior leadership positions (Director, Vice- disparity in enrolment in every skill category. President (VP) or C-suite) is at 32.2% in 2023, For enrolment in technology skills such as Global Gender Gap Report 2023 7

technological literacy (43.7% parity) and AI and – DEI programmes to close gender gaps: In the big data (33.7%), which are among the top 10 private sector, the scope of gender parity action skills projected to grow, there is less than 50% by pioneering 昀椀rms has begun to broaden from parity and progress has been sluggish. Across a focus on the workforce to whole-of-business all skill categories, the gender gaps tend to approaches encompassing inclusive design, widen as pro昀椀ciency levels increase. However, inclusive supply chains and community impact. when women do enrol, they tend to attain The World Economic Forum’s 2023 Future of most pro昀椀ciency levels across skill categories Jobs Survey suggests that more than two-thirds studied in less time compared to men. of the organizations surveyed have implemented a Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) – Gender gaps in political leadership: Much programme. The majority (79%) of companies like in the case of representation of women in surveyed are implementing DEI programmes business leadership, gender gaps in political with a focus on women. leadership continue to persist. Although there has been an increase in the number Increasing women’s economic participation and of women holding political decision-making achieving gender parity in leadership, in both posts worldwide, achieving gender parity business and government, are two key levers for remains a distant goal and regional disparities addressing broader gender gaps in households, are signi昀椀cant. As of 31 December 2022, societies and economies. Collective, coordinated approximately 27.9% of the global population, and bold action by private- and public-sector equivalent to 2.12 billion people, live in countries leaders will be instrumental in accelerating progress with a female head of state. While this indicator towards gender parity and igniting renewed growth experienced stagnation between 2013 and and greater resilience. Recent years have seen 2021, 2022 witnessed a signi昀椀cant increase. major setbacks and the state of gender parity still Another recent positive trend is observed for the varies widely by company, industry and economy. share of women in parliaments. In 2013, only Yet, a growing number of actors have recognized 18.7% of parliament members globally were the importance and urgency of taking action, and women among the 76 countries with consistent evidence on effective gender parity initiatives is data. By 2022, this number had risen steadily to solidifying. We hope the data and analysis provided 22.9%. Signi昀椀cant strides have also been made in this report can further accelerate the speed of in terms of women’s representation in local travel towards parity by catalysing and informing government globally. Out of the 117 countries action by public- and private-sector leaders in their with available data since 2017, 18 countries, efforts to close the global gender gap. including Bolivia (50.4%), India (44.4%) and France (42.3%), have achieved representation of women of over 40% in local governance. Global Gender Gap Report 2023 8

June 2023 Global Gender Gap Report 2023 1 Benchmarking gender gaps, 2023 The Global Gender Gap Index was 昀椀rst introduced The goal of the report is to offer a consistent annual by the World Economic Forum in 2006 to metric for the assessment of progress over time. benchmark progress towards gender parity and Using the methodology introduced in 2006, the compare countries’ gender gaps across four index and the analysis focus on benchmarking dimensions: economic opportunities, education, parity between women and men across countries health and political leadership. and regions. FIGURE 1.1 The Global Gender Gap Index Framework The level of progress toward gender parity (the parity score) for each indicator is calculated as Subindex 1 the ratio of the value of each indicator for women Economic Participation and Opportunity to the value for men. A parity score of 1 indicates full parity. The gender gap is the distance from full Subindex 2 parity. Educational Attainment The analysis in this report is focused on assessing Subindex 3 gender gaps between women and men across Health and Survival economic, educational, health and political outcomes based on the data available (Figure 1.1). Subindex 4 Political Empowerment For further information on the index methodology, please refer to Appendix B. Source World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Index, 2023. 1.1 Country coverage To ensure a global representation of the gender It should be noted that there may be time lags in gap, the report aims to cover as many economies the data collection and validation processes across as possible. For a country to be included, it must the organizations from which the data is sourced, report data for a minimum 12 of the 14 indicators and that all results should be interpreted within a that comprise the index. We also aim to include range of global, regional and national contextual the latest data available, reported within the last 10 factors. The Economy Pro昀椀les at the end of the years. report provide a large range of additional data. The report this year covers 146 countries. In this edition, Croatia rejoins the index, whereas Guyana drops out. Among the 146 countries included this year are a set of 102 countries that have been covered in all editions since the inaugural one in 2006. Scores based on this constant set of countries are used to compare regional and global aggregates across time. Global Gender Gap Report 2023 9

1.2 Global results The Global Gender Gap score in 2023 for all 146 Table 1.1 shows the 2023 Global Gender Gap countries included in this edition stands at 68.4% rankings and the scores for all 146 countries closed. Considering the constant sample of 145 included in this year’s report. Although no country countries covered in the 2022 and 2023 editions, has yet achieved full gender parity, the top nine the overall score changed from 68.1% to 68.4%, an countries (Iceland, Norway, Finland, New Zealand, improvement of 0.3 percentage points compared Sweden, Germany, Nicaragua, Namibia and to last year’s edition. When considering the 102 Lithuania) have closed at least 80% of their gap. For countries covered continuously from 2006 to 2023, the 14th year running, Iceland (91.2%) takes the top the gap is 68.6% closed. position. It also continues to be the only country to have closed more than 90% of its gender gap. The Compared to last year, progress towards narrowing global top 昀椀ve is completed by three other Nordic the gender gap has been more widespread: 42 of countries – Norway (87.9%, 2nd), Finland (86.3%, the 145 economies covered in both the 2022 and 3rd) and Sweden (81.5%, 5th) – and one country 2023 editions improved their gender parity score from East Asia and the Paci昀椀c – New Zealand by at least 1 percentage point since the previous (85.6%, 4th). Additionally, from Europe, Germany edition and 40 other countries registered gains (81.5%) moves up to 6th place (from 10th), of less than 1 percentage point. The economies Lithuania (80.0.%) returns to the top 10 economies, with the greatest increase in score (gains of 4 taking 9th place, and Belgium (79.6%) joins the top percentage points or more) are Liberia (score: 10 for the 昀椀rst time in 10th place. One country from 76%, +5.1 percentage points since the previous Latin America (Nicaragua, 81.1%) and one from edition), Estonia (78.2%, +4.8 percentage points), Sub-Saharan Africa (Namibia, 80.2%) – complete Bhutan (68.2%, +4.5 percentage points), Malawi this year’s top 10, taking the 7th and 8th positions, (67.6%, +4.4 percentage points), Colombia (75.1%, respectively. The two countries that drop out of the +4.1 percentage points) and Chile (77.7%, +4.1 top 10 in 2023 are Ireland (79.5%,11th, down from percentage points). 9th place) and Rwanda (79.4%, 12th, down from 6th place in 2022). While there is an increase in the number of countries registering at least a marginal improvement, such progress is mitigated by an increase in the number of countries with declining scores steeper than 1 percentage point (from 12 in 2022 to 35 in 2023). Global Gender Gap Report 2023 10

TABLE 1.1 The Global Gender Gap Index 2023 rankings Rank Country Score Rank Rank Country Score Rank Score change change Score change change 0–1 2022 2022 0–1 2022 2022 1 Iceland 0.912 +0.004 - 74 Thailand 0.711 +0.002 +5 █ █ 2 Norway 0.879 +0.034 +1 75 Ethiopia 0.711 +0.001 -1 █ █ 3 Finland 0.863 +0.003 -1 76 Georgia 0.708 -0.022 -21 █ █ 4 New Zealand 0.856 +0.014 - 77 Kenya 0.708 -0.021 -20 █ █ 5 Sweden 0.815 -0.007 - 78 Uganda 0.706 -0.017 -17 █ █ 6 Germany 0.815 +0.014 +4 79 Italy 0.705 -0.015 -16 █ █ 7 Nicaragua 0.811 +0.001 - 80 Mongolia 0.704 -0.010 -10 █ █ 8 Namibia 0.802 -0.005 - 81 Dominican Republic 0.704 +0.001 +3 █ █ 9 Lithuania 0.800 +0.001 +2 82 Lesotho 0.702 +0.002 +5 █ █ 10 Belgium 0.796 +0.003 +4 83 Israel 0.701 -0.026 -23 █ █ 11 Ireland 0.795 -0.010 -2 84 Kyrgyzstan 0.700 - +2 █ █ 12 Rwanda 0.794 -0.017 -6 85 Zambia 0.699 -0.025 -23 █ █ 13 Latvia 0.794 +0.023 +13 86 Bosnia and Herzegovina 0.698 -0.012 -13 █ █ 14 Costa Rica 0.793 -0.003 -2 87 Indonesia 0.697 +0.001 +5 █ █ 15 United Kingdom 0.792 +0.012 +7 88 Romania 0.697 -0.001 +2 █ █ 16 Philippines 0.791 +0.009 +3 89 Belize 0.696 +0.002 +6 █ █ 17 Albania 0.791 +0.004 +1 90 Togo 0.696 -0.001 +1 █ █ 18 Spain 0.791 +0.002 -1 91 Paraguay 0.695 -0.012 -11 █ █ 19 Moldova, Republic of 0.788 -0.001 -3 92 Cambodia 0.695 +0.005 +6 █ █ 20 South Africa 0.787 +0.005 - 93 Greece 0.693 +0.005 +7 █ █ 21 Switzerland 0.783 -0.012 -8 94 Cameroon 0.693 +0.002 +3 █ █ 22 Estonia 0.782 +0.048 +30 95 Timor-Leste 0.693 -0.037 -39 █ █ 23 Denmark 0.780 +0.017 +9 96 Brunei Darussalam 0.693 +0.013 +8 █ █ 24 Jamaica 0.779 +0.031 +14 97 Azerbaijan 0.692 +0.005 +4 █ █ 25 Mozambique 0.778 +0.025 +9 98 Mauritius 0.689 +0.011 +7 █ █ 26 Australia 0.778 +0.040 +17 99 Hungary 0.689 -0.010 -11 █ █ 27 Chile 0.777 +0.041 +20 100 Ghana 0.688 +0.016 +8 █ █ 28 Netherlands 0.777 +0.009 - 101 Czech Republic 0.685 -0.024 -25 █ █ 29 Slovenia 0.773 +0.029 +10 102 Malaysia 0.682 +0.001 +1 █ █ 30 Canada 0.770 -0.002 -5 103 Bhutan 0.682 +0.045 +23 █ █ 31 Barbados 0.769 +0.005 -1 104 Senegal 0.680 +0.012 +8 █ █ 32 Portugal 0.765 -0.001 -3 105 Korea, Republic of 0.680 -0.010 -6 █ █ 33 Mexico 0.765 +0.001 -2 106 Cyprus 0.678 -0.018 -13 █ █ 34 Peru 0.764 +0.015 +3 107 China 0.678 -0.004 -5 █ █ 35 Burundi 0.763 -0.013 -11 108 Vanuatu 0.678 +0.008 +3 █ █ 36 Argentina 0.762 +0.006 -3 109 Burkina Faso 0.676 +0.017 +6 █ █ 37 Cabo Verde 0.761 +0.024 +8 110 Malawi 0.676 +0.044 +22 █ █ 38 Serbia 0.760 -0.019 -15 111 Tajikistan 0.672 +0.009 +3 █ █ 39 Liberia 0.760 +0.051 +39 112 Sierra Leone 0.667 -0.005 -3 █ █ 40 France 0.756 -0.035 -25 113 Bahrain 0.666 +0.034 +18 █ █ 41 Belarus 0.752 +0.002 -5 114 Comoros 0.664 +0.033 +20 █ █ 42 Colombia 0.751 +0.041 +33 115 Sri Lanka 0.663 -0.007 -5 █ █ 43 United States of America 0.748 -0.021 -16 116 Nepal 0.659 -0.033 -20 █ █ 44 Luxembourg 0.747 +0.011 +2 117 Guatemala 0.659 -0.006 -4 █ █ 45 Zimbabwe 0.746 +0.012 +5 118 Angola 0.656 +0.018 +7 █ █ 46 Eswatini 0.745 +0.017 +12 119 Gambia 0.651 +0.010 +2 █ █ 47 Austria 0.740 -0.041 -26 120 Kuwait 0.651 +0.018 +10 █ █ 48 Tanzania, United Republic of 0.740 +0.020 +16 121 Fiji 0.650 -0.026 -14 █ █ 49 Singapore 0.739 +0.005 - 122 Côte d'Ivoire 0.650 +0.018 +11 █ █ 50 Ecuador 0.737 -0.005 -9 123 Myanmar 0.650 -0.027 -17 █ █ 51 Madagascar 0.737 +0.002 -3 124 Maldives 0.649 +0.001 -7 █ █ 52 Suriname 0.736 -0.002 -8 125 Japan 0.647 -0.002 -9 █ █ 53 Honduras 0.735 +0.030 +29 126 Jordan 0.646 +0.007 -4 █ █ 54 Lao People's Democratic Republic 0.733 - -1 127 India 0.643 +0.014 +8 █ █ 55 Croatia* 0.730 n/a n/a 128 Tunisia 0.642 -0.001 -8 █ █ 56 Bolivia (Plurinational State of) 0.730 -0.004 -5 129 Türkiye 0.638 -0.001 -5 █ █ 57 Brazil 0.726 +0.030 +37 130 Nigeria 0.637 -0.002 -7 █ █ 58 Panama 0.724 -0.019 -18 131 Saudi Arabia 0.637 +0.001 -4 █ █ 59 Bangladesh 0.722 +0.008 +12 132 Lebanon 0.628 -0.015 -13 █ █ 60 Poland 0.722 +0.012 +17 133 Qatar 0.627 +0.011 +4 █ █ 61 Armenia 0.721 +0.023 +28 134 Egypt 0.626 -0.008 -5 █ █ 62 Kazakhstan 0.721 +0.003 +3 135 Niger 0.622 -0.013 -7 █ █ 63 Slovakia 0.720 +0.003 +4 136 Morocco 0.621 -0.003 - █ █ 64 Botswana 0.719 - +2 137 Guinea 0.617 -0.030 -19 █ █ 65 Bulgaria 0.715 -0.025 -23 138 Benin 0.616 +0.004 - █ █ 66 Ukraine 0.714 +0.007 +15 139 Oman 0.614 +0.006 - █ █ 67 Uruguay 0.714 +0.004 +5 140 Congo, Democratic Republic of the 0.612 +0.036 +4 █ █ 68 El Salvador 0.714 -0.013 -9 141 Mali 0.605 +0.003 - █ █ 69 Montenegro 0.714 -0.018 -15 142 Pakistan 0.575 +0.011 +3 █ █ 70 Malta 0.713 +0.010 +15 143 Iran (Islamic Republic of) 0.575 -0.002 - █ █ 71 United Arab Emirates 0.712 -0.004 -3 144 Algeria 0.573 -0.030 -4 █ █ 72 Viet Nam 0.711 +0.006 +11 145 Chad 0.570 -0.008 -3 █ █ 73 North Macedonia 0.711 -0.005 -4 146 Afghanistan 0.405 -0.030 - █ █ Eurasia and East Asia Europe Latin America Middle East North America Southern Sub-Saharan Central Asia and the Pacific and the Caribbean and North Africa Asia Africa Source Note World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Index, 2023. “–” indicates score or rank is unchanged from the previous year. “n/a” indicates that the country was not covered in previous editions. * New to index in 2023 Global Gender Gap Report 2023 11

1.3 Performance by subindex This section discusses the global gender gap When looking at the sample of 145 countries scores across the four main components included in both the 2022 and 2023 editions, results (subindexes) of the index: Economic Participation show that this year’s progress is mainly caused and Opportunity, Educational Attainment, Health by a signi昀椀cant improvement on the Educational and Survival, and Political Empowerment. In doing Attainment gap and more modest increases for the so, it aims to illuminate and explore the factors that Health and Survival and Political Empowerment are driving the overall average global gender gap subindexes. The Economic Participation and score. Opportunity gender parity score has, however, receded since last year. Summarized in Figure 1.2, this year’s results show that across the 146 countries covered by the 2023 The score distributions across each subindex index, the Health and Survival gender gap has offer a more detailed picture of the disparities closed by 96%, Educational Attainment by 95.2%, in country-speci昀椀c gender gaps across the four Economic Participation and Opportunity by 60.1% dimensions. Figure 1.3 marks the distribution of and Political Empowerment by 22.1%. individual country scores attained both overall and by subindex. FIGURE 1.2 The state of gender gaps, by subindex Percentage of the gender gap closed to date, 2023 The Global Gender Gap Index 68.4% Economic Participation and 60.1% Opportunity subindex Educational Attainment subindex 95.2% Health and Survival subindex 96.0% Political Empowerment subindex 22.1% 0 25 50 75 100 Percentage points Source Note World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Index, 2023. Population-weighted averages, 146 countries. More than two-thirds (69.2%) of countries score and Opportunity has not changed since last year: above the 2023 population-weighted average the difference between the highest scores (89.5%) Gender Gap Index score (68.4%). Similar to 2022, and the country with the lowest scores (18.8%) Afghanistan (40.5%) ranks last, at the lower end of remains extensive (70.8%). the distribution, with a difference of 27.8 percentage points compared to the mean. In fact, Afghanistan Countries that report relatively even access for registers the lowest performance across all men and women when it comes to Economic subindexes, with the exception of the Health and Participation and Opportunity include economies Survival subindex, where it takes the 141st position, as varied as Liberia (89.5%), Jamaica (89.4%), ranking below the bottom 5th percentile. The Moldova (86.3%), Lao PDR (85.1%), Belarus country scoring penultimate in the global ranking (81.9%), Burundi (81.0%) and Norway (80%). At the is Chad (57.0%), which deviates from the average bottom of the distribution, apart from Afghanistan, score by 11.3 percentage points. the countries that attained less than 40% parity include Algeria (31.7%), Iran (34.4%), Pakistan Health and Survival, followed by Educational (36.2%) and India (36.7%). Attainment, continue to display the least amount of variation of scores, whereas the Economic A closer look at performance across the 昀椀ve Participation and Opportunity and Political indicators composing this subindex reveals that Empowerment subindexes continue to show the an important source of gender inequality stems widest dispersion of scores. The range of scores from the overall underrepresentation of women in in this year’s gender gap in Economic Participation the labour market. The global population-weighted Global Gender Gap Report 2023 12

score indicates that, on average, only 64.9% of at the subset of 145 countries included in both the gender gap in labour-force participation has 2022 and 2023, the number of economies with been closed. Comparing the 102-country constant full gender parity in Educational Attainment has sample scores of 63.8% for 2023 and 62.9% increased from 21 to 25. Cross-country scores for 2022, this marks a partial recovery. Chapter on this dimension are less dispersed than for the 2 examines recent dynamics in labour-force Economic Participation or Political Empowerment participation and related labour-market outcomes in subindices, with the majority (80.1%, or 117 out of more detail. 146) of participating countries having closed at least 95% of their educational gender gap. Similar to Though stark income gaps continue to hinder last year, Afghanistan is the only country where the economic gender parity, with almost half (48.1%) educational gender parity score is below the 50% of the overall earned income gap yet to close, mark, at 48.2%. At the bottom of the distribution, results indicate that many countries experienced we also encounter the Sub-Saharan countries improvements since last year. Ninety-six countries of Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, (out of the 145 included in 2022 and 2023) Guinea, Angola, Niger and Mali – all with scores progressed in bridging income gaps. The highest- above 60%, but below 80% in educational parity scoring countries on this dimension include Liberia, (between 63.7%-77.9%). followed by Zimbabwe (97.6%), Tanzania (90.3%), Burundi (88.3%), Barbados (88.1%) and Norway Across indicators of the subindex, gender parity is (85.1%), which all stand at above 85% parity. At lowest for literacy rate: globally, 94% of the gender the bottom of the distribution, Iran (17.1%), Algeria gap in the proportion of those over 15 years of (19.2%) and Egypt (19.7%) display some of the age who are literate has closed. Fifty-six countries largest inequalities between the incomes of men have achieved full parity in literacy rate, whereas and women, scoring less than 20% parity. Afghanistan and Sub-Saharan countries such as Mali, Liberia, Chad and Guinea all register parity When it comes to wages for similar work, the only scores below 55%. When it comes to enrolment countries in which the gender gap is perceived in primary education, full parity scores are more as more than 80% closed are Albania (85.8%) widespread: 65 countries register equivalent rates and Burundi (84.1%). Merely a quarter of the 146 of enrolment in primary education for boys and for economies included in this year’s edition score girls. The rest of the countries included this year between 70%-80% on this indicator. These include display at least 90% parity, apart from the Sub- some of the most advanced economies, such as Saharan countries of Mali, Guinea and Chad, which Iceland (78.4% of gap closed), Singapore (78.3%), score within the 80.4%-89.9% range. United Arab Emirates (77.6%), United States (77.3%), Finland (76.3%), Qatar (74.5%), Saudi Cross-national variation is wider for both secondary Arabia (74.1%), Lithuania (74.1%), Slovenia (73.5%), and tertiary enrolment. Whereas most countries Bahrain (72.8%), Estonia (71.4%), Barbados (135) included in this edition closed at least 80% (71.2%), Luxembourg (70.4%), New Zealand of their gender gap in secondary enrolment, a (70.4%), Switzerland (70.3%), and Latvia (70.1%). handful of countries remain below this threshold, The lowest-ranking countries on this dimension with Congo (64% of the gap closed), Chad (58.3%) are Croatia (49.7% of the gap closed) and Lesotho and Afghanistan (57.1) ranking last. Geographical (49.4%). Compared to last year’s performance, disparities are even starker for tertiary education. Bolivia, El Salvador and South Africa registered the While 101 countries display full parity on this largest improvements in score, of 5 percentage indicator, including Cambodia as the most recent to points or more. reach the 1 parity mark this year, 18 more countries stand within the 80.2%-99.5% range, while Cross-country disparities are more pronounced in several countries from Sub-Saharan Africa (such terms of the gender gap in senior, managerial and as Burkina Faso, Mali and Côte d’Ivoire), Southern legislative roles, which globally stands at 42.9%. Asia (Afghanistan), and Eurasia and Central Asia Ten countries assessed this year – six of which (Tajikistan) still have between 21.7% (Côte d’Ivoire) located in Sub-Saharan Africa – report parity on this and 71% (Afghanistan) of their gaps left to close. indicator. Afghanistan, Pakistan and Algeria rank at the bottom, with less than 5% of professionals The Health and Survival subindex displays the in senior positions being women. When it comes highest level of gender parity globally (at 96%) as to professional and technical positions, 71% well as the most clustered distribution of scores. of the gender gap has been closed globally. The majority of countries (91.1%) register at most Whereas women’s representation in managerial 2 percentage points above the average, and only roles relative to men’s has improved by at least 1 a handful of others (13 out of 146) register at most percentage points for 38 countries, gender parity 2.4 percentage points below the average. Twenty- in professional and technical roles has improved for six countries – most from Europe, Latin America only 20 countries by the same measure (at least 1 and the Caribbean, and Sub-Saharan Africa 1 percentage points). – display the top score of 98% parity, whereas Qatar, Viet Nam and populous countries such as Educational Attainment is the subindex with Azerbaijan, India and China all score below the 95% the second-highest global parity score, with only mark. 4.8% of the gender gap left to close. When looking Global Gender Gap Report 2023 13

Qatar’s lower overall ranking is driven by relatively Rica (52.4%), Sweden (51.2%) and Chile (50.2%). lower parity in terms of healthy life expectancy. The lowest parity scores are found for: Myanmar Though in most countries women tend to outlive (4.7%), Nigeria (4.1%), Iran (3.1%), Lebanon men, in 昀椀ve Middle Eastern and North African (2.1%), Vanuatu (0.6%) and Afghanistan (0%). countries (Morocco, 99.9%; Bahrain, 99.3%; Algeria, 99%; Jordan, 98.7%; Qatar, 95.5%), Iceland and Bangladesh are the only countries one from Sub-Saharan Africa (Mali, 99.3%) and where women have held the highest political two from Southern Asia (Pakistan, 99.9%, and position in a country for a higher number of years Afghanistan, 97.1%), the reverse is true. than men. In 67 other countries, women have never served as head of state in the past 50 years. For Viet Nam, Azerbaijan, India and China, the relatively low overall rankings on the Health and In terms of the share of women in ministerial Survival subindex is explained by skewed sex ratios positions, 11 out of 146 countries, led by Albania, at birth. Compared to top scoring countries that Finland and Spain, have 50% or more ministers register a 94.4% gender parity at birth, the indicator who are women. However, 75 countries have 20% stands at 92.7% for India (albeit an improvement or less female ministers. Further, populous countries over last edition) and below 90% for Viet Nam, such as India, Türkiye and China have less than China and Azerbaijan. 7% ministers who are women and countries like Azerbaijan, Saudi Arabia and Lebanon have none. Finally, the Political Empowerment subindex registers once again the largest gender gap, at As regards to parity in the number of seats in only 22.1% of the gap closed and the greatest national parliaments, 昀椀ve countries stand at full spread of scores across countries. Iceland parity: Mexico, Nicaragua, Rwanda, the United stands out as best performer, with a 90.1% parity Arab Emirates and (as of this year’s edition) New score, which is 13.6 percentage points greater Zealand. The countries with the least representation than the country ranking second (Norway) and of women in parliament (less than 5%) are Maldives 69 percentage points above the median global (4.8% of the gender gap closed), Qatar (4.6%), score (21.1%). In addition to the 昀椀rst two ranked, Nigeria (3.7%), Oman (2.4%) and Vanuatu (1.9%). only 10 other countries out of the 146 included Though still below the 40% parity threshold, Benin this year score above the 50% parity score: and Malta saw the largest improvements for this New Zealand (72.5%), Finland (70%), Germany indicator, experiencing a rise of 26.6 and 23.2 (63.4%), Nicaragua (62.6%), Bangladesh (55.2%), percentage points, respectively. Mozambique (54.2%), Rwanda (54.1%), Costa Global Gender Gap Report 2023 14

FIGURE 1.3 Range of scores, Global Gender Gap Index and subindexes, 2023 India Rwanda Global Gender Gap index 0.684 Saudi Arabia United States Iceland India Italy Germany Norway Lao, PDR Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex 0.601 Pakistan Mexico Indonesia United States Netherlands Educational Attainment subindex 0.952 Chad Nigeria Peru India Health and Survival subindex 0.960 China Viet Nam Japan United States Costa Rica Kenya Political Empowerment subindex 0.221 United Arab Emirates France Sweden Iceland 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 Score (0-1 scale) Population-weighted average Source Note World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Index, 2023. Blue diamonds correspond to population-weighted averages. 1.4 Progress over time By calculating how much the gap has, on average, The Economic Participation and Opportunity reduced each year since the report’s 昀椀rst edition in subindex now stands at 59.8% based on the 102 2006, using a constant sample of 102 countries, countries in the constant sample (non-constant it is possible to project how many years it will take score 60.1%). This subindex is the only one that to close each of the gender gaps for each of the receded compared to 2022. There is a drop of 0.2 dimensions tracked. The 17-year trajectory of global percentage points since 2022, but an improvement gender gaps is charted accordingly in Figure 1.4. of 4.1 percentage points since 2006. The ebbing of the upward trend seen in last year’s edition can This year’s results leave the total progress made be partially attributed to the drop in the subindex towards gender parity at an overall 4.1 percentage- scores for 66 economies including highly populated point gain since 2006. Hence, on average, over economies such as China, Indonesia, Nigeria, etc. the past 17 years, the gap has been reduced by As a result, it will take another 169 years to close only 0.24 percentage points per year. If progress the economic gender gap. towards gender parity proceeds at the same average speed observed between the 2006 and The Educational Attainment subindex displays the 2023 editions, the overall global gender gap is highest gender parity score (96.1%) on the basis of projected to close in 131 years, compared to a 102 countries in the constant sample (non-constant projection of 132 years in 2022. This suggests that score 95.2%). The 0.8 percentage-point increase the year in which the gender gap is expected to since last year places it from second to top-ranked close remains 2154, as progress is moving at the across all subindices. While the development has same rate as last year. not been unfaltering over time – accelerating then plateauing at various points in time and dropping Global Gender Gap Report 2023 15

FIGURE 1.4 Evolution of the Global Gender Gap Index and subindexes over time Evolution in scores, 2006-2023 1 Years to close the gap 16 Educational Attainment n.a. Health and Survival 0.9 0.8 0.7 131 Global Genger Gap Index 0.6 169 Economic Participation and Opportunity 0.5 e (0-1, parity) Scor 0.4 0.3 162 Political Empowerment 0.2 0.1 0 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019* 2020 2021 2022 2023 Edition Source Note World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Index, 2023. Population-weighted averages for the the 102 economies featured in all editions of the index, from 2006–2023. The fourteenth edition of the Global Gender Gap Index, titled The Global Gender Gap Report 2020, was released in December 2019. There is no corresponding edition for 2019. in 2017-2018 and 2022 – the time-series analysis Based on the constant sample of 102 countries shows a de昀椀nitive upward trend overall. Its included in each edition from 2006 to 2023, the improved performance as well as a steady pace of global Political Empowerment gender gap this progress on average over the 2006-2023 period year is 22.5% (non-constant score 22.1%), which is leads to an estimation of 16 years to close the gap. a slight improvement of 0.1 percentage points over 2022. A slower pace of improvement, however, The Health and Survival gender parity score means that it will now take another 162 years stands at 95.9% based on the constant sample to completely close this gap, a signi昀椀cant step of 102 countries (non-constant score 96%). It is backwards compared to the 2022 edition. Yet, the a modest improvement compared to last year 2023 score is the highest absolute increase of all (+0.2 percentage points) and an actual drop of 0.3 four subindexes since 2006: 8.2 percentage points percentage points compared to 2006. Despite this compared to 4.4 percentage points for Educational slight long-term drop, the index has consistently Attainment, which is the subindex with the second- stayed above the 95% mark since the inception of greatest improvement. the index in 2006. Global Gender Gap Report 2023 16

TABLE 1.2 The Global Gender Gap Index 2023, results by subindex Economic Participation and Opportunity Educational Attainment Rank Country Score (0–1) Rank Country Score (0–1) Rank Country Score (0–1) Rank Country Score (0–1) 1 Liberia 0.895 74 Austria 0.692 1 Argentina 1.000 74 Vanuatu 0.991 2 Jamaica 0.894 75 Israel 0.688 1 Belgium 1.000 75 Belarus 0.991 3 Moldova, Republic of 0.863 76 Paraguay 0.685 1 Botswana 1.000 76 Portugal 0.991 4 Barbados 0.860 77 Netherlands 0.684 1 Canada 1.000 77 Zimbabwe 0.991 5 Lao PDR 0.851 78 Sierra Leone 0.684 1 Colombia 1.000 78 Australia 0.991 6 Eswatini 0.838 79 Peru 0.683 1 Czech Republic 1.000 79 Iceland 0.991 7 Belarus 0.819 80 Ghana 0.682 1 Dominican Republic 1.000 80 Cyprus 0.990 8 Burundi 0.810 81 South Africa 0.676 1 Estonia 1.000 81 Greece 0.990 9 Botswana 0.807 82 Greece 0.676 1 Finland 1.000 82 Germany 0.989 10 Zimbabwe 0.801 83 Congo, Dem. Rep. of the 0.676 1 France 1.000 83 Lithuania 0.989 11 Norway 0.800 84 Costa Rica 0.676 1 Honduras 1.000 84 Norway 0.989 12 Madagascar 0.800 85 Panama 0.674 1 Ireland 1.000 85 Sri Lanka 0.988 13 Togo 0.796 86 Brazil 0.670 1 Israel 1.000 86 United Arab Emirates 0.988 14 Iceland 0.796 87 Indonesia 0.666 1 Latvia 1.000 87 Saudi Arabia 0.986 15 Sweden 0.795 88 Germany 0.665 1 Lesotho 1.000 88 Eswatini 0.985 16 Kenya 0.791 89 Malaysia 0.664 1 Malaysia 1.000 89 Viet Nam 0.985 17 Philippines 0.789 90 Bolivia (Plurinational State of) 0.658 1 Malta 1.000 90 Lebanon 0.984 18 Albania 0.786 91 Comoros 0.657 1 Namibia 1.000 91 Maldives 0.984 19 Namibia 0.784 92 Colombia 0.657 1 Netherlands 1.000 92 Bolivia (Plurinational State of) 0.984 20 Finland 0.783 93 Cyprus 0.652 1 New Zealand 1.000 93 Qatar 0.982 21 United States of America 0.780 94 Lesotho 0.648 1 Nicaragua 1.000 94 Guatemala 0.982 22 Latvia 0.775 95 Argentina 0.644 1 Slovakia 1.000 95 Cabo Verde 0.981 23 Singapore 0.774 96 Chile 0.642 1 Slovenia 1.000 96 Cambodia 0.981 24 Thailand 0.772 97 Malta 0.641 1 Sweden 1.000 97 Timor-Leste 0.980 25 Estonia 0.771 98 Nicaragua 0.640 1 Uruguay 1.000 98 Bosnia and Herzegovina 0.980 26 Lithuania 0.767 99 Croatia* 0.639 26 India 1.000 99 Türkiye 0.980 27 Azerbaijan 0.766 100 Mauritius 0.637 27 Kazakhstan 1.000 100 Madagascar 0.979 28 Kazakhstan 0.765 101 Czech Republic 0.636 28 Georgia 1.000 101 Zambia 0.979 29 Brunei Darussalam 0.760 102 Uganda 0.623 29 Kyrgyzstan 1.000 102 Switzerland 0.978 30 Slovenia 0.760 103 El Salvador 0.619 30 Luxembourg 1.000 103 Myanmar 0.977 31 Viet Nam 0.749 104 Italy 0.618 31 Costa Rica 0.999 104 Korea, Republic of 0.977 32 Cabo Verde 0.747 105 Tajikistan 0.618 32 Philippines 0.999 105 Ghana 0.974 33 Mongolia 0.745 106 Gambia 0.609 33 Albania 0.999 106 Indonesia 0.972 34 Portugal 0.745 107 Angola 0.605 34 United Kingdom 0.999 107 Lao PDR 0.964 35 Vanuatu 0.742 108 North Macedonia 0.605 35 Armenia 0.999 108 Tanzania, United Republic of 0.964 36 Canada 0.740 109 Malawi 0.602 36 Romania 0.999 109 Bhutan 0.963 37 Suriname 0.740 110 Mexico 0.601 37 Serbia 0.999 110 Rwanda 0.963 38 Australia 0.740 111 Côte d'Ivoire 0.601 38 Croatia* 0.998 111 Peru 0.960 39 Bulgaria 0.738 112 Bosnia and Herzegovina 0.601 39 Spain 0.998 112 Iran (Islamic Republic of) 0.960 40 Zambia 0.734 113 Myanmar 0.600 40 Denmark 0.998 113 Oman 0.957 41 Ireland 0.732 114 Korea, Republic of 0.597 41 Montenegro 0.998 114 Gambia 0.954 42 New Zealand 0.732 115 Fiji 0.588 42 Ecuador 0.998 115 Morocco 0.953 43 United Kingdom 0.731 116 Ethiopia 0.587 43 South Africa 0.998 116 Algeria 0.951 44 Belgium 0.728 117 Guatemala 0.580 44 Brunei Darussalam 0.997 117 Tunisia 0.950 45 China 0.727 118 Kuwait 0.579 45 Paraguay 0.997 118 Comoros 0.949 46 Denmark 0.727 119 Guinea 0.576 46 Fiji 0.997 119 Egypt 0.943 47 Uruguay 0.726 120 Timor-Leste 0.574 47 Japan 0.997 120 Burundi 0.942 48 Spain 0.722 121 Niger 0.570 48 North Macedonia 0.997 121 Tajikistan 0.942 49 Belize 0.720 122 Bahrain 0.564 49 Panama 0.997 122 Bangladesh 0.936 50 Slovakia 0.718 123 Japan 0.561 50 Poland 0.997 123 China 0.935 51 France 0.717 124 Sri Lanka 0.555 51 Kuwait 0.997 124 Sierra Leone 0.932 52 Armenia 0.716 125 Jordan 0.542 52 Belize 0.996 125 Senegal 0.926 53 Tanzania, United Republic of 0.715 126 Chad 0.538 53 Moldova, Republic of 0.996 126 Uganda 0.924 54 Nigeria 0.715 127 Lebanon 0.538 54 Azerbaijan 0.996 127 Nepal 0.918 55 Ukraine 0.714 128 United Arab Emirates 0.536 55 Austria 0.996 128 Côte d'Ivoire 0.902 56 Montenegro 0.710 129 Benin 0.530 56 Ukraine 0.996 129 Malawi 0.897 57 Luxembourg 0.710 130 Saudi Arabia 0.521 57 Bahrain 0.995 130 Mozambique 0.896 58 Cambodia 0.710 131 Maldives 0.512 58 Hungary 0.995 131 Liberia 0.896 59 Bhutan 0.708 132 Qatar 0.508 59 United States of America 0.995 132 Cameroon 0.895 60 Burkina Faso 0.708 133 Türkiye 0.500 60 Italy 0.995 133 Burkina Faso 0.893 61 Ecuador 0.705 134 Mali 0.489 61 Thailand 0.995 134 Kenya 0.858 62 Hungary 0.701 135 Oman 0.488 62 Mexico 0.994 135 Ethiopia 0.854 63 Switzerland 0.700 136 Nepal 0.476 63 Bulgaria 0.994 136 Togo 0.837 64 Poland 0.699 137 Senegal 0.475 64 Chile 0.994 137 Nigeria 0.826 65 Dominican Republic 0.699 138 Tunisia 0.451 65 Barbados 0.994 138 Pakistan 0.825 66 Honduras 0.699 139 Bangladesh 0.438 66 Jordan 0.994 139 Benin 0.802 67 Rwanda 0.699 140 Egypt 0.420 67 Mongolia 0.994 140 Mali 0.779 68 Georgia 0.697 141 Morocco 0.404 68 Jamaica 0.993 141 Niger 0.769 69 Serbia 0.697 142 India 0.367 69 El Salvador 0.993 142 Angola 0.738 70 Cameroon 0.694 143 Pakistan 0.362 70 Suriname 0.993 143 Guinea 0.710 71 Kyrgyzstan 0.694 144 Iran (Islamic Republic of) 0.344 71 Mauritius 0.993 144 Congo, Dem. Rep. of the 0.683 72 Romania 0.693 145 Algeria 0.317 72 Singapore 0.993 145 Chad 0.637 73 Mozambique 0.692 146 Afghanistan 0.188 73 Brazil 0.992 146 Afghanistan 0.482 Eurasia and East Asia Europe Latin America Middle East North America Southern Sub-Saharan Central Asia and the Pacific and the Caribbean and North Africa Asia Africa Source Note World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Index, 2023. * New to index in 2023 Global Gender Gap Report 2023 17

TABLE 1.2 The Global Gender Gap Index 2023, results by subindex Health and Survival Political Empowerment Rank Country Score (0–1) Rank Country Score (0–1) Rank Country Score (0–1) Rank Country Score (0–1) 1 Belarus 0.980 74 Bosnia and Herzegovina 0.970 1 Iceland 0.901 74 Cameroon 0.210 1 Belize 0.980 75 Tanzania, United Republic of 0.970 2 Norway 0.765 75 Kenya 0.209 1 Botswana 0.980 76 France 0.970 3 New Zealand 0.725 76 Madagascar 0.201 1 Brazil 0.980 77 Austria 0.970 4 Finland 0.700 77 Tunisia 0.197 1 Cabo Verde 0.980 78 United States of America 0.970 5 Germany 0.634 78 Mali 0.192 1 Dominican Republic 0.980 79 Serbia 0.969 6 Nicaragua 0.626 79 Niger 0.185 1 El Salvador 0.980 80 Malaysia 0.969 7 Bangladesh 0.552 80 Slovakia 0.183 1 Eswatini 0.980 81 Tunisia 0.969 8 Mozambique 0.542 81 Indonesia 0.181 1 Guatemala 0.980 82 Nepal 0.969 9 Rwanda 0.541 82 Montenegro 0.180 1 Hungary 0.980 83 Gambia 0.968 10 Costa Rica 0.524 83 Lesotho 0.179 1 Kyrgyzstan 0.980 84 Comoros 0.968 11 Sweden 0.503 84 Eswatini 0.178 1 Lesotho 0.980 85 Ecuador 0.968 12 Chile 0.502 85 Egypt 0.175 1 Lithuania 0.980 86 Philippines 0.968 13 South Africa 0.497 86 Togo 0.173 1 Malawi 0.980 87 Kuwait 0.968 14 Switzerland 0.491 87 Ukraine 0.172 1 Mauritius 0.980 88 Montenegro 0.968 15 Mexico 0.490 88 Korea, Republic of 0.169 1 Mongolia 0.980 89 Australia 0.968 16 Belgium 0.486 89 Viet Nam 0.166 1 Mozambique 0.980 90 Egypt 0.968 17 Ireland 0.482 90 Morocco 0.165 1 Namibia 0.980 91 Belgium 0.968 18 Spain 0.475 91 Georgia 0.163 1 Poland 0.980 92 Barbados 0.968 19 United Kingdom 0.472 92 Benin 0.159 1 Romania 0.980 93 Canada 0.968 20 Lithuania 0.466 93 Tajikistan 0.156 1 Slovakia 0.980 94 Jamaica 0.967 21 Netherlands 0.460 94 Uruguay 0.152 1 Sri Lanka 0.980 95 Italy 0.967 22 Peru 0.450 95 Pakistan 0.152 1 Uganda 0.980 96 Greece 0.967 23 Namibia 0.443 96 Israel 0.150 1 Uruguay 0.980 97 Senegal 0.967 24 Denmark 0.432 97 Mauritius 0.148 1 Zambia 0.980 98 Spain 0.967 25 Ethiopia 0.431 98 Bulgaria 0.148 1 Zimbabwe 0.980 99 Nigeria 0.967 26 Argentina 0.429 99 Bahrain 0.146 27 Burundi 0.979 100 Türkiye 0.966 27 Latvia 0.424 100 Kazakhstan 0.146 28 Bulgaria 0.979 101 New Zealand 0.966 28 Albania 0.419 101 Lao PDR 0.140 29 South Africa 0.979 102 Guinea 0.966 29 Australia 0.412 102 Greece 0.140 30 Togo 0.979 103 Madagascar 0.966 30 Philippines 0.409 103 Maldives 0.139 31 Suriname 0.979 104 Sierra Leone 0.966 31 Estonia 0.377 104 Dominican Republic 0.138 32 Estonia 0.979 105 United Kingdom 0.965 32 Serbia 0.376 105 Chad 0.137 33 Côte d'Ivoire 0.978 106 Timor-Leste 0.965 33 Canada 0.374 106 Sri Lanka 0.130 34 Nicaragua 0.978 107 Fiji 0.965 34 Colombia 0.373 107 Kyrgyzstan 0.128 35 Croatia* 0.978 108 Luxembourg 0.965 35 United Arab Emirates 0.363 108 Czech Republic 0.128 36 Ghana 0.978 109 Israel 0.964 36 Slovenia 0.358 109 Burkina Faso 0.125 37 Czech Republic 0.978 110 Honduras 0.964 37 Senegal 0.353 110 Paraguay 0.125 38 Cambodia 0.978 111 Ireland 0.964 38 Portugal 0.352 111 Ghana 0.119 39 Burkina Faso 0.978 112 Denmark 0.964 39 France 0.338 112 Côte d'Ivoire 0.118 40 Moldova, Republic of 0.977 113 Niger 0.964 40 Cabo Verde 0.334 113 Romania 0.117 41 Argentina 0.977 114 Saudi Arabia 0.964 41 Burundi 0.320 114 China 0.114 42 Thailand 0.977 115 Switzerland 0.964 42 Bolivia (Plurinational State of) 0.317 115 Cambodia 0.112 43 Congo, Dem. Rep. of the 0.976 116 Iran (Islamic Republic of) 0.964 43 Luxembourg 0.315 116 Congo, Dem. Rep. of the 0.111 44 Angola 0.976 117 Peru 0.964 44 Moldova, Republic of 0.314 117 Cyprus 0.109 45 Ukraine 0.976 118 Sweden 0.963 45 Tanzania, United Republic of 0.309 118 Türkiye 0.106 46 Korea, Republic of 0.976 119 United Arab Emirates 0.963 46 Angola 0.305 119 Zambia 0.102 47 Kazakhstan 0.975 120 Cyprus 0.963 47 Croatia 0.305 120 Thailand 0.101 47 Myanmar 0.975 121 Maldives 0.962 48 Austria 0.303 121 Mongolia 0.099 49 Mexico 0.975 122 Bhutan 0.962 49 Uganda 0.297 122 Malaysia 0.098 50 Lao PDR 0.975 123 Liberia 0.962 50 Liberia 0.287 123 Guatemala 0.094 51 Colombia 0.975 124 Netherlands 0.962 51 North Macedonia 0.283 124 Jordan 0.093 52 Latvia 0.975 125 Bolivia (Plurinational State of) 0.962 52 Honduras 0.278 125 Bhutan 0.093 53 Kenya 0.975 126 Bangladesh 0.962 53 Ecuador 0.278 126 Belize 0.090 54 Paraguay 0.975 127 Norway 0.961 54 Nepal 0.276 127 Botswana 0.088 55 Rwanda 0.974 128 Iceland 0.961 55 El Salvador 0.265 128 Sierra Leone 0.087 56 Georgia 0.974 129 Oman 0.961 56 Brazil 0.263 129 Comoros 0.083 57 Cameroon 0.973 130 Morocco 0.961 57 Jamaica 0.263 130 Hungary 0.079 58 Panama 0.973 131 Malta 0.961 58 Barbados 0.256 131 Saudi Arabia 0.077 59 Japan 0.973 132 Pakistan 0.961 59 India 0.253 132 Gambia 0.073 60 Costa Rica 0.973 133 Albania 0.960 60 Timor-Leste 0.253 133 Qatar 0.071 61 Benin 0.973 134 North Macedonia 0.960 61 Panama 0.252 134 Azerbaijan 0.071 62 Portugal 0.973 135 Mali 0.959 62 Malta 0.251 135 Algeria 0.065 63 Slovenia 0.972 136 Bahrain 0.959 63 United States of America 0.248 136 Brunei Darussalam 0.061 64 Germany 0.972 137 Algeria 0.958 64 Italy 0.241 137 Kuwait 0.059 65 Vanuatu 0.971 138 Jordan 0.957 65 Bosnia and Herzegovina 0.240 138 Japan 0.057 66 Singapore 0.971 139 Armenia 0.955 66 Suriname 0.232 139 Fiji 0.052 67 Ethiopia 0.971 140 Brunei Darussalam 0.953 67 Malawi 0.224 140 Oman 0.051 68 Lebanon 0.971 141 Afghanistan 0.952 68 Singapore 0.220 141 Myanmar 0.047 69 Chile 0.970 142 India 0.950 69 Belarus 0.217 142 Nigeria 0.041 70 Tajikistan 0.970 143 Qatar 0.947 70 Guinea 0.217 143 Iran (Islamic Republic of) 0.031 71 Finland 0.970 144 Viet Nam 0.946 71 Armenia 0.215 144 Lebanon 0.021 72 Chad 0.970 145 China 0.937 72 Zimbabwe 0.214 145 Vanuatu 0.006 73 Indonesia 0.970 146 Azerbaijan 0.936 73 Poland 0.211 146 Afghanistan 0.000 Eurasia and East Asia Europe Latin America Middle East North America Southern Sub-Saharan Central Asia and the Pacific and the Caribbean and North Africa Asia Africa Source Note World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Index, 2023. * New to index in 2023 Global Gender Gap Report 2023 18

1.5 Performance by region The Global Gender Gap Report 2023 categorizes decline. North America (-1.9 percentage points) and countries into eight regions: Eurasia and Central the Middle East and North Africa (-0.09 percentage Asia, East Asia and the Paci昀椀c, Europe, Latin points) suffer more signi昀椀cant setbacks in overall America and the Caribbean, Middle East and North gender parity. Africa, North America, Southern Asia, and Sub- Saharan Africa. Countries in each regional group The longer-term trends offer further insights into are listed in Appendix A. progress in the regional gender parity pro昀椀les. In comparison to the inaugural edition in 2006, Gender parity in Europe (76.3%) surpasses the the Latin America and the Caribbean region parity level in North America (75%) this year to rank has improved the most, with an increase of 8.4 昀椀rst among regions. Closely behind Europe and percentage points over the past 17 years. Europe North America is Latin America and the Caribbean, (+6.1 percentage points) and Sub-Saharan Africa with 74.3% parity. Trailing more than 5 percentage (+5.2 percentage points) are the other two regions points behind Latin America and the Caribbean are that have improved by more than 5 percentage Eurasia and Central Asia (69%) as well as East Asia points. North America (+4.5 percentage points), and the Paci昀椀c (68.8%). Sub-Saharan Africa ranks the Middle East and North Africa (+4.2 percentage 6th (68.2%), slightly below the global weighted points) and Southern Asia (+4.1 percentage points) average score (68.3%). Southern Asia (63.4%) have improved by more than 4 percentage points, overtakes the Middle East and North Africa (62.6%), though parity scores in all three regions have which is, in 2023, the region furthest away from backslid in recent editions. Eurasia and Central parity. Asia (+ 3.2 percentage points) and East Asia and the Paci昀椀c (+ 2.8 percentage points) have seen the Using the 102-country constant sample to slowest to progress since 2006. assess trends over time suggests that Southern Asia as well as Latin America and the Caribbean A more nuanced picture emerges from the experienced an improvement of 1.1 percentage heat map in Figure 1.6, which disaggregates points and 1.7 percentage points, respectively, regional scores by subindex and represents since the last edition. Sub-Saharan Africa improves higher levels of parity using a darker colour. Most marginally (+0.1 percentage points) while Eurasia regions have achieved relatively higher parity in and Central Asia (-0.01 percentage points), East Educational Attainment and Health and Survival. Asia and the Paci昀椀c (-0.02 percentage points), and The advancement in Economic Participation Europe (-0.02 percentage points) show a slight and Opportunity is more uneven, with Southern FIGURE 1.5 Gender gap closed to date, by region Europe 76.3% North America 75.0% Latin America and 74.3% the Caribbean Eurasia and 69.0% Central Asia East Asia and 68.8% the Pacific Sub-Saharan Africa 68.2% Southern Asia 63.4% Middle East and 62.6% North Africa 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 Percentage points Source Note World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Index, 2023. Population-weighted averages for the 146 economies featured in the Global Gender Gap Index 2023. Global Gender Gap Report 2023 19

FIGURE 1.6 Regional performance 2023, by subindex Subindexes Overall Index Economic Participation Educational Health Political and Opportunity Attainment and Survival Empowerment Eurasia and Central Asia 69.0% 68.8% 98.9% 97.4% 10.9% East Asia and the Pacific 68.8% 71.0% 95.5% 94.9% 14.0% Europe 76.3% 69.7% 99.6% 97.0% 39.1% Latin America and the Caribbean 74.3% 65.2% 99.2% 97.6% 35.0% Middle East and North Africa 62.6% 44.0% 95.9% 96.4% 14.0% North America 75.0% 77.6% 99.5% 96.9% 26.1% Southern Asia 63.4% 37.2% 96.0% 95.3% 25.1% Sub-Saharan Africa 68.2% 67.2% 86.0% 97.2% 22.6% Global average 68.4% 60.1% 95.2% 96.0% 22.1% Parity 0% 50% 100% Source Note World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Index, 2023. Population-weighted averages for the 146 economies featured in the Global Gender Gap Index 2023. The percentages are indicative of the gender gap that has been closed. FIGURE 1.7 Regional gender gaps Evolution in scores, 2006–2023 1 0.9 0.8 0.7 e (0-1, parity)0.6 Scor 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019* 2020 2021 2022 2023 Edition Eurasia and Central Asia East Asia and the Pacific Europe Latin America and the Caribbean Middle East and North Africa North America Southern Asia Sub-Saharan Africa Source Note World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Index, 2023. Population-weighted averages for the 102 economies featured in all editions of the Global Gender Gap Index, from 2006–2023. The fourteenth edition of the Global Gender Gap Index, titled The Global Gender Gap Report 2020, was released in December 2019. There is no corresponding edition for 2019. Global Gender Gap Report 2023 20

Asia closing 37.2% of the gender gap and North and Tajikistan have made at least a 1 percentage- America closing more than double. Regions point improvement. While more than one-昀椀fth of continue to have the most signi昀椀cant gaps in the ministers in Moldova and Ukraine are women, Political Empowerment subindex, with only Latin Azerbaijan continues to be one of the handful America and the Caribbean as well as Europe countries with a male-only cabinet. Further, 昀椀ve of recording more than 35% parity. the 10 countries in the region have more than 25% women parliamentarians. With female presidents in Georgia and Moldova, there has been some Eurasia and Central Asia improvement in female head-of-state representation in the last 50 years. At 69% parity, Eurasia and Central Asia ranks 4th out of the eight regions on the overall Gender East Asia and the Paci昀椀c Gap Index. Based on the aggregated scores of the constant sample of countries included since 2006, the parity score since the 2020 edition East Asia and Paci昀椀c is at 68.8% parity, marking the has stagnated, although there has been an 昀椀fth-highest score out of the eight regions. Progress improvement of 3.2 percentage points since 2006. towards parity has been stagnating for over a Moldova, Belarus and Armenia are the highest- decade and the region registers a 0.2 percentage- ranking countries in the region, while Azerbaijan, point decline since the last edition. While 11 out of Tajikistan and Türkiye rank the lowest. The 19 countries improve, one stays the same and eight difference in parity between the highest- and the (including China, the world’s second-most populous lowest-ranked country is 14.9 percentage points. At country) recede on the overall index. New Zealand, the current rate of progress, it will take 167 years for the Philippines and Australia have the highest parity the Eurasia and Central Asia region to reach gender at the regional level, with Australia and New Zealand parity. also being the two most-improved economies in the region. On the other hand, Fiji, Myanmar and Japan Regional gender parity on Economic Participation are at the bottom of the list, with Fiji, Myanmar and and Opportunity has been steadily increasing. Timor-Leste registering the highest declines. At the Overall, 68.8% of the gender gap has closed, current rate of progress, it will take 189 years for the which is a 0.5 percentage-point improvement since region to reach gender parity. the last edition. Six out of 10 countries, led by Moldova, Belarus and Azerbaijan, have at least 70% Compared to the last edition, six out of 19 countries parity on this subindex. All countries in the region improved on the Economic Participation and except Kyrgyzstan have made varying degrees of Opportunity subindex, depleting the regional parity progress since the 2022 edition, with Moldova and score by 1.1% to 71.1%. Nine out of 17 countries Armenia making the most progress. Furthermore, that have the data have shown drops in the share of all countries in the region have advanced towards women in senior of昀椀cial positions. However, 13 out parity in estimated earned income. Türkiye and of 19 countries improved parity in estimated earned Tajikistan demonstrate the least parity on Economic income since the last edition. Overall, Lao PDR, the Participation and Opportunity, with Türkiye being Philippines and Singapore register the highest parity the only country that has closed less than 60% of for the subindex and Fiji, Timor-Leste and Japan the gap on this subindex. register the lowest. Eight out of 10 countries have more than 99% At 95.5%, East Asia and the Paci昀椀c has the parity on the Educational Attainment subindex, second-lowest score on the Educational Attainment resulting in 98.9% parity for the region. Türkiye and subindex compared to other regions. Malaysia and Ukraine, the region’s two most populous countries, New Zealand are at full parity, along with nine other have a persistent disparity in secondary enrolment. countries in the region, with more than 99% scores. Barring Türkiye and Tajikistan, all countries have China, Lao PDR and Indonesia, with more than 1.7 attained parity in enrolment in tertiary education. billion people, have the lowest parity. Cambodia and Thailand are the only countries in this region At 97.4% parity, Eurasia and Central Asia has with more than 1 percentage-point increase in parity only three out of 10 countries that have less than over 2022. Thailand improves parity in enrolment in 97% parity for the Health and Survival subindex. secondary education while Cambodia improves on Azerbaijan and Armenia, home to more than 13 literacy rate and enrolment in primary and tertiary million people combined, have some of the lowest education. sex ratios at birth in the world. Finally, seven out of the 10 countries have reached parity in healthy life On the Health and Survival subindex, Singapore expectancy. attains gender parity in sex ratio at birth, joining seven other countries across the world with the Compared to other regions, Eurasia and Central same achievement. However, 11 out of 19 countries Asia has the lowest gender parity in Political saw declining parity in sex ratio. This contributes Empowerment and suffers a 1 percentage-point to the region’s slight depletion of parity on this setback since 2022. Its score of 10.9% is barely half subindex, by 0.02% to 94.9%. the global score of 22.1%. Only Armenia, Ukraine Global Gender Gap Report 2023 21