Startup Tools: Web Application Frameworks

By On December 18, 2012

By On December 18, 2012

When it comes to technology, it can be confusing out there for the business-minded (read: non-technical) co-founder.

When it comes to technology, it can be confusing out there for the business-minded (read: non-technical) co-founder.

Do those snowboard-loving, flip-flop wearing, EDM-listening, tattoo-having jackanapes-for-developers ridicule you with their fancy words and assault you with offensive acronyms? Do you think that JSON was that guy with the hockey mask and chainsaw in "Friday the 13th"? Thought Ruby was a reference to Grandma's dear friend at the nursing home?

Take heart, my friend, there is still hope. I am the co-founder and CTO of a startup called Speek, and I am here to help. Here is a quick guide to some of the popular technologies that today's startups use to change the world.

1. Node.jsNode.js is a platform built on Chrome's JavaScript runtime designed to easily build fast, scalable network applications. Node.js uses an event-driven, non-blocking I/O model that makes it lightweight and efficient, perfect for data-intensive real-time applications that run across distributed devices.

Translation: Node.js makes it much easier, faster and efficient for your development team to do cool shit in your app in real-time that will melt your users' faces.

Why should you care?Historically, it was fairly time-intensive and very resource-intensive to crunch data or logic or to otherwise do stuff in real time within your app. Developers had to either use a request/response pattern via web services, or use crazy AJAX-based black magic. Web services are asynchronous by nature, so this was problematic. AJAX could make things appear to be happening more real-time, but took a toll on server and/or client resources that made it harder to scale efficiently.

Node.js allows developers to do things in real-time more easily, in way that scales pretty damn well.

What's it good for?

- Chat apps

- Synchronous drawing or note-taking features

- Collaboration or communication apps

- Snazzy search and search results manipulation

- Anything that requires stuff to happen in a synchronous or real-time manner

Pretty much everyone is using Node in some way, shape or form these days. So many companies are using node in some way, shape, or form today that it would be easier to list those not using it. Some notable users are:

2. Ruby on RailsRuby on Rails is an open-source web framework optimized for programmer happiness and sustainable productivity. It lets you write beautiful code by favoring convention over configuration. Ruby on Rails was invented by 37 Signals - the same folks that make Basecamp, Highrise, Campfire and some other cool products.

Translation: Ruby on Rails lets your developers build cool shit really, really quickly. It will also help you recruit developers because they love Ruby on Rails.

Why should you care?Ruby on Rails should shorten your development cycles to build products and features. Added bonus: It will let you "fail fast" with concepts and features, because it makes it very easy to throw prototypes and tests together.

What's it good for?Ruby on Rails should be your main programming language for your Web app.

Who's using it? 3. NoSQLIn short, NoSQL database management systems are useful when working with a huge quantity of data when a relational model isn't required. The data can be structured, but NoSQL is most useful when what really matters is the ability to store and retrieve great quantities of data, not the relationships between elements.

Translation: NoSQL databases are great for storing mass amounts of data in a really dumb way.

Why should you care?Web and mobile products are starting to be expected to do more in real-time or at least very quickly. User expectations are very high. NoSQL, combined with Node, will save you a ton of development time.

What's it good for?Your typical relational databases like MySQL, SQL Server and Oracle are great for storing highly-structured and relational data but are not ideal great at storing up simple data very quickly so that the logic or interface layer of your app can manipulate it. NoSQL saves the day.

Where can I find it? Some popular NoSQL databases are:

Who's using it? Pretty much everyone is using NoSQL databases these days, but to name a few:

4. GithubGithub is a cloud-based implementation of the Git source code repository system. Git is a free and open source distributed version control system designed to handle a wide array of projects with speed and efficiency.

Translation: Github gives the source code behind your app a place to live. Since it's hosted, no setup or maintenance is needed. It also comes with some additional bells and whistles that make automating builds and deployments faster and easier, and is very conducive to distributed development teams. Lastly, developers love Github.

Why should you care?The days of having your entire development team sitting in the same room together are gone for most startups. Github makes it easier for distributed development teams to avoid source code messes. Further, since Github is a SaaS, you avoid spending precious time on keeping the source code management system up and running.

What's it good for?

- Distributed and non-distributed development teams

- Any kind of source code management

- Continuous deployment and integration environments

- Any Web or mobile development efforts

In 2006, Amazon Web Services (AWS) began offering IT infrastructure services to businesses in the form of web services- - now commonly known as cloud computing. One of the key benefits of cloud computing is the opportunity to replace up-front capital infrastructure expenses with low variable costs that scale with your business. EC2 stands for Elastic Cloud Compute and is one of several offerings that make up AWS.

Translation: AWS allows you to host your Web apps in a highly scalable way yet only paying for the resources you actually use. It also allows your tech team to help themselves in real time when they need to add servers.

Why should you care?AWS tends to be cheaper and faster than traditional hosting. It is also "elastic" in nature. This means that you can set up your AWS "servers" to spin up and spin down based on traffic and load so you can theoretically handle infinite load. AWS also saves you from being blocked, waiting for some low-level network engineer at your hosting company to plug a cord in. AWS has a full-blown API and admin panel that allows your techies to help themselves and change things instantly.

What's it good for?AWS is great for variable load or traffic. It's also good for sites that get have seasonal spikes. AWS will not save you any real money in the very early days, in terms of hosting. Nor will it likely AWS will likely not make financial sense when you hit super-high constant load. However, AWS is great fromor when you first start growing to when you've officially made it.

Who's using it?AWS is another one being used by that is pretty much being used by everyone these days, including my company Speek, as well as:

Here are some of the more popular examples:

6. JSONJSON (JavaScript Object Notation) is a lightweight data-interchange format. It is easy for humans to read and write., and It is easy for machines to parse and generate. It is based on a subset of the JavaScript pProgramming lLanguage. JSON is a text format that is completely language independent but uses conventions that are familiar to programmers of the C-family of languages, including C, C++, C#, Java, JavaScript, Perl, Python, and many others. These properties make JSON an ideal data-interchange language.

Translation: You've heard of SOAP and REST right? JSON plays nicely with REST is newer and better than traditional XML. It also plays very nicely with the fancy new UI interactivity that is all the rage these days.

Why should you care?All of that whiz-bang interactive stuff you want your web or mobile product do will be done faster, easier, better with JSON.

What's it good for?JSON is great for exchanging or retrieving data that needs to be manipulated, massaged, mashed up or otherwise tweaked.

Who's using it?EVERYONE.

7. Continuous Integration (CI) and Continuous Deployment (CD)In software engineering, continuous integration (CI) is the practice of merging all developer code with a shared mainline/trunk several times a day. Its main aim is to prevent integration problems.

CI intended to be used in combination with automated unit tests written through the practices of tTest- driven development. Initially, meant this was conceived of as running and verifying all unit tests and verifying they all passed before committing to the mainline. Later elaborations of the concept introduced build servers, which automatically run the unit tests periodically - or even after every commit- and report the results to the developers.

Continuous Deployment is a process by which software is released several times throughout the day - in minutes versus days, weeks, or months.

Translation: When more than one developer is writing code, it makes itis hell to merge everyone's code together and ensure shit didn't break. Continuous Integration is an automated process that ensures integration hell doesn't occur. Continuous Deployment takes CI one-step further and even by automatinges deploymenting stuff to live servers in small chunks so that you avoid the risks of big bang releases that can also break shit.

Why should you care?Continuous Integration and Continuous Deployment will allow your development team to get more stuff done, break less stuff and push to production very frequently. Also, since CI and CD typically require a suite of unit tests, they indirectly help you save time on regression testing.

What's it good for?Everything everywhere.

Who's using it?Everyone everywhere who builds software that doesn't suck.

8. WebRTCWebRTC is a free, open project that enables web browsers with Real-Time Communications (RTC) capabilities via simple Javascript APIs. The WebRTC components have been optimized to best serve this purpose.

Translation: You know how bad it sucks to try and do real-time audio or video in a web browser using flash? WebRTC makes it so that you no longer need to use flash. You can now do things like VoIP and Video Chat natively inside the browser.

Why should you care?WebRTC is HOT right now and is moving very quickly. It is already supported in Opera browsers and in Chrome 23. Firefox will likely fully support it next, with Safari to follow. IE may or may not ever support it, but who cares about them, anyway?.

There are major players backing WebRTC like Google. Also, major players in the telephony space have already released WebRTC clients - like Twilio.

WebRTC is going to be a total game changer.

What's it good for?WebRTC will be good for a real-time communications in a web or mobile browser. It will be specifically good for real-time audio and video communication using nothing more than a browser (no downloads or installs required).

Who's using it?[Original image courtesy CircaSassy]

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page.

A web application framework ( WAF) is a software framework that is designed to support the development of dynamic websites, web applications, web services and web resources. The framework aims to alleviate the overhead associated with common activities performed in web development. For example, many frameworks provide libraries for database access, templating frameworks and session management, and they often promote code reuse. For a comparison of concrete web application frameworks, see Comparison of web application frameworks.

This article Please help to lacks historical information on the subject. Specifically: sources and the dates some of the ideas arose should be added. add historical material to help counter systemic bias towards recent information. (June 2013)

As the design of the World Wide Web was not inherently dynamic, early hypertext consisted of hand-coded HTML that was published on web servers. Any modifications to published pages needed to be performed by the pages' author. To provide a dynamic web page that reflected user inputs, the Common Gateway Interface (CGI) standard was introduced for interfacing external applications with web servers. CGI could adversely affect server load, though, since each request had to start a separate process.

Programmers wanted tighter integration with the web server to enable high-traffic web applications. The Apache HTTP Server, for example, supports modules that can extend the web server with arbitrary code executions (such as mod perl) or forward specific requests to a web server that can handle dynamic content (such as mod jk). Some web servers (such as Apache Tomcat) were specifically designed to handle dynamic content by executing code written in some languages, such as Java.

Around the same time, full integrated server/language development environments first emerged, such as WebBase and new languages specifically for use in the web started to emerge, such as ColdFusion, PHP and Active Server Pages.

While the vast majority of languages available to programmers to use in creating dynamic web pages have libraries to help with common tasks, web applications often require specific libraries that are useful in web applications, such as creating HTML (for example, JavaServer Faces). Eventually, mature, "full stack" frameworks appeared, that often gathered multiple libraries useful for web development into a single cohesive software stack for web developers to use. Examples of this include ASP.NET, JavaEE (Servlets), WebObjects, web2py, OpenACS, Catalyst, Mojolicious, Ruby on Rails, Django, Zend Framework, Yii, CakePHP and Symfony.

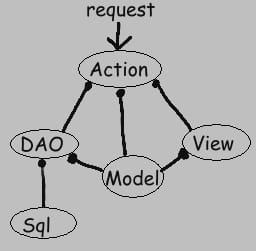

Most web application frameworks are based on the model-view-controller (MVC) pattern.

Many frameworks follow the MVC architectural pattern to separate the data model with business rules from the user interface. This is generally considered a good practice as it modularizes code, promotes code reuse, and allows multiple interfaces to be applied. In web applications, this permits different views to be presented, such as web pages for humans, and web service interfaces for remote applications.

Push-based vs. pull-based

Most MVC frameworks follow a push-based architecture also called "action-based". These frameworks use actions that do the required processing, and then "push" the data to the view layer to render the results. Struts, Django, Ruby on Rails, Symfony, Yii, Spring MVC, Stripes, Play, CodeIgniter are good examples of this architecture. An alternative to this is pull-based architecture, sometimes also called "component-based". These frameworks start with the view layer, which can then "pull" results from multiple controllers as needed. In this architecture, multiple controllers can be involved with a single view. Struts2, Lift, Tapestry, JBoss Seam, JavaServer Faces, and Wicket are examples of pull-based architectures.

In three-tier organization, applications are structured around three physical tiers: client, application, and database. The database is normally an RDBMS. The application contains the business logic, running on a server and communicates with the client using HTTP. The client, on web applications is a web browser that runs HTML generated by the application layer. The term should not be confused with MVC, where, unlike in three-tier architecture, it is considered a good practice to keep business logic away from the controller, the "middle layer".

Frameworks are built to support the construction of internet applications based on a single programming language, ranging in focus from general purpose tools such as Zend Framework and Ruby on Rails, which augment the capabilities of a specific language, to native-language programmable packages built around a specific user application, such as Content Management systems, some mobile development tools and some portal tools.

For example, Zend Framework.

For example, WikiBase/ WikiWikiWeb.

For example, JBoss Portal.

In web application frameworks, content management is the way of organizing, categorizing, and structuring the information resources like text, images, documents, audio and video files so that they can be stored, published, and edited with ease and flexibility. A content management system (CMS) is used to collect, manage, and publish content, storing it either as components or whole documents, while maintaining dynamic links between components.

Some projects that have historically been termed content management systems have begun to take on the roles of higher-layer web application frameworks. For instance, Drupal's structure provides a minimal core whose function is extended through modules that provide functions generally associated with web application frameworks. The Solodev and Joomla platforms provide a set of APIs to build web and command-line applications. However, it is debatable whether "management of content" is the primary value of such systems, especially when some, like SilverStripe, provide an object-oriented MVC framework. Add-on modules now enable these systems to function as full-fledged applications beyond the scope of content management. They may provide functional APIs, functional frameworks, coding standards, and many of the functions traditionally associated with Web application frameworks.

Web caching is the caching of web documents in order to reduce bandwidth usage, server load, and perceived " lag". A web cache stores copies of documents passing through it; subsequent requests may be satisfied from the cache if certain conditions are met. Some application frameworks provide mechanisms for caching documents and bypassing various stages of the page's preparation, such as database access or template interpretation.

Some web application frameworks come with authentication and authorization frameworks, that enable the web server to identify the users of the application, and restrict access to functions based on some defined criteria. Drupal is one example that provides role-based access to pages, and provides a web-based interface for creating users and assigning them roles.

Many web application frameworks create a unified API to a database backend, enabling web applications to work with a variety of databases with no code changes, and allowing programmers to work with higher-level concepts. For higher performance, database connections should be pooled as e.g. AOLserver does. Additionally, some object-oriented frameworks contain mapping tools to provide object-relational mapping, which maps objects to tuples.

Some frameworks minimize web application configuration through the use of introspection and/or following well-known conventions. For example, many Java frameworks use Hibernate as a persistence layer, which can generate a database schema at runtime capable of persisting the necessary information. This allows the application designer to design business objects without needing to explicitly define a database schema. Frameworks such as Ruby on Rails can also work in reverse, that is, define properties of model objects at runtime based on a database schema.

Other features web application frameworks may provide include transactional support and database migration tools.

A framework's URL mapping facility is the mechanism by which the framework interprets URLs. Some frameworks, such as Drupal and Django, match the provided URL against pre-determined patterns using regular expressions, while some others use URL rewriting to translate the provided URL into one that the underlying engine will recognize. Another technique is that of graph traversal such as used by Zope, where a URL is decomposed in steps that traverse an object graph (of models and views).

A URL mapping system that uses pattern matching or URL rewriting allows more " friendly URLs" to be used, increasing the simplicity of the site and allowing for better indexing by search engines. For example, a URL that ends with "/page.cgi?cat=science&topic=physics" could be changed to simply "/page/science/physics". This makes the URL easier for people to read and hand write, and provides search engines with better information about the structural layout of the site. A graph traversal approach also tends to result in the creation of friendly URLs. A shorter URL such as "/page/science" tends to exist by default as that is simply a shorter form of the longer traversal to "/page/science/physics".

Ajax, shorthand for "", is a web development technique for creating web applications. The intent is to make web pages feel more responsive by exchanging small amounts of data with the server behind the scenes, so that the entire web page does not have to be reloaded each time the user requests a change. This is intended to increase a web page's interactivity, speed, and usability.

Due to the complexity of Ajax programming in JavaScript, there are numerous Ajax frameworks that exclusively deal with Ajax support. Some Ajax frameworks are even embedded as a part of larger frameworks. For example, the jQuery JavaScript library is included in Ruby on Rails.

With the increased interest in developing " Web 2.0" rich media applications, the complexity of programming directly in Ajax and JavaScript has become so apparent that compiler technology has stepped in, to allow developers to code in high-level languages such as Java, Python and Ruby. The first of these compilers was Morfik followed by Google Web Toolkit, with ports to Python and Ruby in the form of Pyjamas and RubyJS following some time after. These compilers and their associated widget set libraries make the development of rich media Ajax applications much more akin to that of developing desktop applications.

Some frameworks provide tools for creating and providing web services. These utilities may offer similar tools as the rest of the web application.

A number of newer Web 2.0 RESTful frameworks are now providing resource-oriented architecture (ROA) infrastructure for building collections of resources in a sort of Semantic Web ontology, based on concepts from Resource Description Framework (RDF).

I had a nerdy conversation on what might be the next mainstream framework for building web products, and in particular whether the node.js community would ultimately create this framework, or if node.js will just be a fad. This blog post is a bit of a deviation from my usual focus around marketing, so just ignore if you have no interest in the area.

Here's the summary:

- Programming languages/frameworks are like marketplaces - they have network effects

- Rails, PHP, and Visual Basic were all successful because they made it easy to build form-based applications

- Form-based apps are a popular/dominant design pattern

- The web is moving to products with real-time updates, but building real-time apps hard

- Node.js could become a popular framework by making it dead simple to create modern, real-time form-based apps

- Node.js will be niche if it continues to emphasize Javascript purity or high-scalability

The longer argument below:

Large communities of novice/intermediate programmers are important

One of the biggest technology decisions for building a new product is the choice of development language and framework. Right now for web products, the most popular choice is Ruby on Rails - it's used to build some of the most popular websites in the world, including Github, Scribd, Groupon, and Basecamp.

Programming languages are like marketplaces - you need a large functional community of people both demanding and contributing code, documentation, libraries, consulting dollars, and more. It's critical that these marketplaces have scale - it needs to appeal to the large ecosystem of novices, freelancers and consultants that constitute the vast majority of programmers in the world. It turns out, just because a small # of Stanford-trained Silicon Valley expert engineers use something doesn't guarantee success.

Before Rails, the most popular language for the web was PHP, which had a similar value proposition - it was easy to build websites really fast, and it was used by a large group of novice/intermediate programmers as well. This includes a 19-yo Mark Zuckerberg to build the initial version of Facebook. Although PHP gained the reputation of churning out spaghetti code, the ability for people to start by writing HTML and then start adding application logic all in one file made it extremely convenient for development.

And even before Rails and PHP, it was Visual Basic that engaged this same development community. It appealed to novice programmers who could quickly set up an application by dragging-and-dropping controls, write application logic with BASIC, etc.

I think there's a unifying pattern that explains much of the success of these three frameworks.

The power of form-based applications

The biggest "killer app" for all of these languages is how easy it is to build the most common application that mainstream novice-to-intermediate programmers are paid to build: Basic form-based applications.

These kinds of apps let you do a some basic variation of:

- Give the user a form for data-entry

- Store this content in a database

- Edit, view, and delete entries from this database

It turns out that this describes a very high % of useful applications, particularly in business contexts including addressbooks, medical records, event-management, but also consumer applications like blogs, photo-sharing, Q&A, etc. Because of the importance of products in this format, it's no surprise one of Visual Basic's strongest value props was a visual form building tool.

Similarly, what drove a lot of the buzz behind Rails's initial was a screencast below:

How to build a blog engine in 15 min with Rails (presented in 2005)

Even if you haven't done any programming, it's worthwhile to watch the above video to get a sense for how magical it is to get a basic form-based application up and running in Rails. You can get the basics up super quickly. The biggest advantages in using Rails are the built-in data validation and how easy it is to create usable forms that create/update/delete entries in a database.

Different languages/frameworks have different advantages - but easy form-based apps are key

The point is, every new language/framework that gets buzz has some kind of advantage over others- but sometimes these advantages are esoteric and sometimes they tap into a huge market of developers who are all trying to solve the same problem. In my opinion, if a new language primarily helps solve scalability problems, but is inferior in most other respects, then it will fail to attract a mainstream audience. This is because most products don't have to deal with scalability issues, though there's no end to programmers who pick technologies dedicated to scale just in case! But much more often than not, it's all just aspirational.

Contrast this to a language lets you develop on iOS and reach its huge audience - no matter how horrible it is, people will flock to it.

Thus, my big prediction is:

The next dominant web framework will be the one that allows you to build form-based apps that are better and easier than Rails

Let's compare this idea with one of the most recent frameworks/languages that has gotten a ton of buzz is node.js. I've been reading a bit about it but haven't used it much - so let me caveat everything in the second half with my post with that. Anyway, based on what I've seen there's a bunch of different value props ascribed to its use:

- Build server-side applications with Javascript, so you don't need two languages in the backend and frontend

- High-performance/scalability

- Allows for easier event-driven applications

A lot of the demo applications that are built seem to revolve around chat, which is easy to build in node but harder to build in Rails. Ultimately though, in its current form, there's a lot missing from what would be required for node.js to hit the same level of popularity as Rails, PHP, or Visual Basic for that. I'd argue that the first thing that the node.js community has to do is to drive towards a framework that makes modern form-based applications dead simple to build.

What would make a framework based on node.js more mainstream?

Right now, modern webapps like Quora, Asana, Google Docs, Facebook, Twitter, and others are setting the bar high for sites that can reflect changes in data across multiple users in real-time. However, building a site like this in Rails is extremely cumbersome in many ways that the node.js community may be able to solve more fundamentally.

That's why I'd love to see a "Build a blog engine in 15 minutes with node.js" that proves that node could become the best way to build modern form-based applications in the future. In order to do this, I think you'd have to show:

- Baseline functionality around scaffolding that makes it as easy as Rails

- Real-time updates for comment counts, title changes, etc that automatically show across any viewers of the blog

- Collaborative editing of a single blog post

- Dead simple implementation of a real-time feed driving the site's homepage

All of the above features are super annoying to implement in Rails, yet could be easy to do in node. It would be a huge improvement.

Until then, I think people will still continue to mostly build in Rails with a large contingent going to iOS - the latter not due to the superiority of the development platform, but rather because that's what is needed to access iOS users.

UPDATE: I just saw Meteor on Hacker News which looks promising. Very cool.

PS. Get new essays sent to your inbox

Get my weekly newsletter covering what's happening in Silicon Valley, focused on startups, marketing, and mobile.

PHP Freaks is a website dedicated to learning and teaching PHP. Here you will find a forum consisting of 132,227 members who have posted a total of 1,379,780 posts on the forums. Additionally, we have tutorials covering various aspects of PHP and you will find news syndicated from other websites so you can stay up-to-date. Along with the tutorials, the developers on the forum will be able to help you with your scripts, or you may perhaps share your knowledge so others can learn from you.

Django is a high-level Python Web framework that encourages rapid development and clean, pragmatic design.

Developed by a fast-moving online-news operation, Django was designed to handle two challenges: the intensive deadlines of a newsroom and the stringent requirements of the experienced Web developers who wrote it. It lets you build high-performing, elegant Web applications quickly.

Django focuses on automating as much as possible and adhering to the DRY principle.

Dive in by reading the overview →

When you're ready to code, read the installation guide and tutorial.

The Django framework

Object-relational mapper

Define your data models entirely in Python. You get a rich, dynamic database-access API for free - but you can still write SQL if needed.

Automatic admin interface

Save yourself the tedious work of creating interfaces for people to add and update content. Django does that automatically, and it's production-ready.

Elegant URL design

Design pretty, cruft-free URLs with no framework-specific limitations. Be as flexible as you like.

Template system

Use Django's powerful, extensible and designer-friendly template language to separate design, content and Python code.

Cache system

Hook into memcached or other cache frameworks for super performance - caching is as granular as you need.

Internationalization

Django has full support for multi-language applications, letting you specify translation strings and providing hooks for language-specific functionality.

Download

Open source, BSD license

Documentation

Sites that use Django

Bobo is a light-weight framework for creating WSGI web applications.

It's goal is to be easy to learn and remember.

It provides 2 features:

- Mapping URLs to objects

- Calling objects to generate HTTP responses

It doesn't have a templateing language, a database integration layer, or a number of other features that can be provided by WSGI middle-ware or application-specific libraries.

Bobo builds on other frameworks, most notably WSGI and WebOb.

Bobo can be installed in the usual ways, including using the setup.py install command. You can, of course, use Easy Install, Buildout, or pip.

To use the setup.py install command, download and unpack the source distribution and run the setup script:

To run bobo's tests, just use the test command:

You can do this before or after installation.

Bobo works with Python 2.4, 2.5, and 2.6. Python 3.0 support is planned. Of course, when using Python 2.4 and 2.5, class decorator syntax can't be used. You can still use the decorators by calling them with a class after a class is created.

Let's create a minimal web application, "hello world". We'll put it in a file named "hello.py":

This application creates a single web resource, "/hello.html", that simply outputs the text "Hello world".

Bobo decorators, like used in the example above control how URLs are mapped to objects. They also control how functions are called and returned values converted to web responses. If a function returns a string, it's assumed to be HTML and used to construct a response. You can control the content type used by passing a content_type keyword argument to the decorator.

Let's try out our application. Assuming that bobo's installed, you can run the application on port 8080 using [1]:

This will start a web server running on localhost port 8080. If you visit:

http://localhost:8080/hello.html

you'll get the greeting:

The URL we used to access the application was determined by the name of the resource function and the content type used by the decorator, which defaults to "text/html; charset=UTF-8". Let's change the application so we can use a URL like:

We'll do this by providing a URL path:

Here, we passed a path to the decorator. We used a '/' string, which makes a URL like the one above work. (We also omitted the import for brevity.)

We don't need to restart the server to see our changes. The bobo development server automatically reloads the file if it changes.

As its name suggests, the decorator is meant to work with resources that return information, possibly using form data. Let's modify the application to allow the name of the person to greet to be given as form data:

If a function accepts named arguments, then data will be supplied from form data. If we visit:

http://localhost:8080/?name=Sally

We'll get the output:

The decorator will accept , and requests. It's appropriate when server data aren't modified. To accept form data and modify data on a server, you should use the decorator. The decorator works like the decorator accept that it only allows and requests and won't pass data provided in a query string as function arguments.

The and decorators are convenient when you want to just get user input passed as function arguments. If you want a bit more control, you can also get the request object by defining a bobo_request parameter:

The request object gives full access to all of the form data, as well as other information, such as cookies and input headers.

The and decorators introspect the function they're applied to. This means they can't be used with callable objects that don't provide function meta data. There's a low-level decorator, that does no introspection and can be used with any callable:

The decorator always passes the request object as the first positional argument to the callable it's given.

The , , and decorators provide automatic response generation when the value returned by an application isn't a object. The generation of the response is controlled by the content type given to the content_type decorator parameter.

If an application returns a string, then a response is constructed using the string with the content type.

If an application doesn't return a response or a string, then the handling depends on whether or not the content type is 'application/json . For 'application/json , the returned value is marshalled to JSON using the (or simplejson ) module, if present. If the module isn't importable, or if marshaling fails, then an exception will be raised.

If an application returns a unicode string and the content type isn't 'application/json' , the string is encoded using the character set given in the content_type, or using the UTF-8 encoding, if the content type doesn't include a charset parameter.

If an application returns a non-response non-string result and the content type isn't 'application/json' , then an exception is raised.

If an application wants greater control over a response, it will generally want to construct a webob.Response object and return that.

We saw earlier that we could control the URLs used to access resources by passing a path to a decorator. The path we pass can specify a multi-level URL and can have placeholders, which allow us to pass data to the resource as part of the URL.

Here, we modify the hello application to let us pass the name of the greeter in the URL:

Now, to access the resource, we use a URL like:

http://localhost:8080/greeters/myapp?name=Sally

for which we get the output:

Hello Sally! My name is myapp.

We call these paths because they use a syntax inspired loosely by the Ruby on Rails Routing system.

You can have any number of placeholders or constant URL paths in a route. The values associated with the placeholders will be made available as function arguments.

If a placeholder is followed by a question mark, then the route segment is optional. If we change the hello example:

we can use the URL:

http://localhost:8080/greeters?name=Sally

for which we get the output:

Hello Sally! My name is Bobo.

Note, however, if we use the URL:

http://localhost:8080/greeters/?name=Sally

we get the output:

Hello Sally! My name is .

Placeholders must be legal Python identifiers. A placeholder may be followed by an extension. For example, we could use:

Here, we've said that the name must have an ".html" suffix. To access the function, we use a URL like:

http://localhost:8080/greeters/myapp.html?name=Sally

And get:

Hello Sally! My name is myapp.

If the placeholder is optional:

Then we can use a URL like:

http://localhost:8080/greeters?name=Sally

or:

http://localhost:8080/greeters/jim.html?name=Sally

Subroutes

Sometimes, you want to split URL matching into multiple steps. You might do this to provide cleaner abstractions in your application, or to support more flexible resource organization. You can use the subroute decorator to do this. The subroute decorator decorates a callable object that returns a resource. The subroute uses the given route to match the beginning of the request path. The resource returned by the callable is matched against the remainder of the path. Let's look at an example:

With this example, if we visit:

http://localhost:8080/employees/1/summary.html

We'll get the summary for a user. The URL will be matched in 2 steps. First, the path /employees/1 will match the subroute. The class is called with the request and employee id. Then the routes defined for the individual methods are searched. The remainder of the path,/summary.html , matches the route for the summary method. (Note that we provided two decorators for the summary method, which allows us to get to it two ways.) The methods were scanned for routes because we used the keyword argument.

The method has a route that is an empty string. This is a special case that handles an empty path after matching a subroute. The base method will be called for a URL like:

http://localhost:8080/employees/1

which would redirect to:

http://localhost:8080/employees/1/

The method defines another subroute. Because we left off the route path, the method name is used. This returns a Folder instance. Let's look at the Folder class:

The and classes use the decorator. The class decorator scans a class to make routes defined for it's methods available. Using the decorator is equivalent to using the keyword with decorator [2]. Now consider a URL:

http://localhost:8080/employees/1/documents/hobbies/sports.html

which outputs:

I like to ski.

The URL is matched in multiple steps:

- The path /employees/1 matches the class.

- The path matches the method, which returns a using the employee documents dictionary.

- The path matches the method of the class, which returns the dictionary from the documents folder.

- The path /sports.html also matches the method, which returns a using the text for thesports.html key.

5, The empty path matches the method of the class.

Of course, the employee document tree can be arbitrarily deep.

The decorator can be applied to any callable object that takes a request and route data and returns a resource.

Methods and REST

When we define a resource, we can also specify the HTTP methods it will handle. The and decorators will handle GET, HEAD and POST methods by default. The decorator handles POST and PUT methods. You can specify one or more methods when using the , , and decorators:

If multiple resources (resource, query, or post) in a module or class have the same route strings, the resource used will be selected based on both the route and the methods allowed. (If multiple resources match a request, the first one defined will be used [3].)

The ability to provide handlers for specific methods provides support for the REST architectural style. .. _configuration:

The bobo server makes it easy to get started. Just run it with a source file and off you go. When you're ready to deploy your application, you'll want to put your source code in an importable Python module (or package). Bobo publishes modules, not source files. The bobo server provides the convenience of converting a source file to a module.

The bobo command-line server is convenient for getting started, but production applications will usually be configured with selected servers and middleware using Paste Deployment. Bobo includes a Paste Deployment application implementation. To use bobo with Paste Deployment, simply define an application section using the bobo egg:

[app:main] use = egg:bobo bobo_resources = helloapp bobo_configure = helloapp:config employees_database = /home/databases/employees.db [server:main] use = egg:Paste#http host = localhost port = 8080

In this example, we're using the HTTP server that is built into Paste.

The application section () contains bobo options, as well as application-specific options. In this example, we used the bobo_resources option to specify that we want to use resources found in the hellowapp module, and the bobo_configure option to specify a configuration handler to be called with configuration data.

You can put application-specific options in the application section, which can be used by configuration handlers. You can provide one or more configuration handlers using the bobo_configure option. Each configuration handler is specified as a module name and global name [4] separated by a colon.

Configuration handlers are called with a mapping object containing options from the application section and from the DEFAULT section, if present, with application options taking precedence.

To start the server, you'll run the paster script installed with PasteScript and specify the name of your configuration file:

You'll need to install Paste Script to use bobo with Paste Deployment.

See Assembling and running the example with Paste Deployment and Paste Script for a complete example.

Bottle is a fast, simple and lightweight WSGI micro web-framework for Python. It is distributed as a single file module and has no dependencies other than the Python Standard Library.

- Routing: Requests to function-call mapping with support for clean and dynamic URLs.

- Templates: Fast and pythonic built-in template engine and support for mako, jinja2 and cheetah templates.

- Utilities: Convenient access to form data, file uploads, cookies, headers and other HTTP-related metadata.

- Server: Built-in HTTP development server and support for paste, fapws3, bjoern, Google App Engine, cherrypy or any other WSGI capable HTTP server.

Example: "Hello World" in a bottle

Run this script or paste it into a Python console, then point your browser to http://localhost:8080/hello/world. That's it.

Download and Install

Install the latest stable release via PyPI () or download bottle.py (unstable) into your project directory. There are no hard [1] dependencies other than the Python standard library. Bottle runs with Python 2.5+ and 3.x.

User's Guide

Start here if you want to learn how to use the bottle framework for web development. If you have any questions not answered here, feel free to ask the mailing list.

Knowledge Base

A collection of articles, guides and HOWTOs.

Development and Contribution

These chapters are intended for developers interested in the bottle development and release workflow.

License

Code and documentation are available according to the MIT License:

Copyright (c) 2012, Marcel Hellkamp. Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy of this software and associated documentation files (the "Software"), to deal in the Software without restriction, including without limitation the rights to use, copy, modify, merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell copies of the Software, and to permit persons to whom the Software is furnished to do so, subject to the following conditions: The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all copies or substantial portions of the Software. THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED "AS IS", WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM, OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE SOFTWARE.

The Bottle logo however is NOT covered by that license. It is allowed to use the logo as a link to the bottle homepage or in direct context with the unmodified library. In all other cases please ask first.

Footnotes

Why wait? It's free!

Sign up now and get a free Nerd Life shirt

Get immediate code-level visibility and build faster, more reliable web and mobile applications.

Create Free AccountNo credit card required * No commitment

Web Application Monitoring

New Relic is the only dashboard you need to keep an eye on application health and availability. Real user monitoring, server utilization, code-level diagnostics, and more. Get direct visibility into your Ruby, PHP, Java, .NET, Python and Node.js apps. New Relic is a better way to monitor and boost performance for your entire web app environment. Complete visibility anytime you want it.

Learn More About Web App Monitoring

With Web App Monitoring you can...

Get Started Today

Sign up and get a free T-shirt

Real User Monitoring

Get browser performance data directly from real end-users and see exactly what their experiences are by monitoring transactions traces, JavaScript rendering speed and network latency all from their perspective.

Server Monitoring

Get critical web server resource data in the context of real-time application performance, whether your apps are deployed in the cloud or in your data center. It's powerful, and it's free.

Loved & Trusted

New Relic captures 150 billion metrics each day from millions of apps

Mobile Application Monitoring

The same powerful New Relic performance data is now available for your native iOS and Android apps. For the first time ever, see the end-to-end performance of your app with deep and actionable insight into real users, sessions and finger swipes as they happen.

Works with the following languages:

It's more than just code that can slow down your app.

Your App Code

We're sure your code is awesome, Now track activity, get alerts and create custom metrics.

Network Performance

Is it a background service or a carrier slowing you down? Is it regional or global? Never wonder again.

Device Profile

Know what devices and operating systems to focus on, track user activity, and get performance breakdowns.

End-to-End Visibility

Slow code on the device, non-responsive API calls, slow backend services. Alert the right team immediately.

Plugins

New Relic's open SaaS Platform allows you to download and use customized plugins so you can get visibility into your entire technology stack within our first-class UI and data visualizations. Don't see an app you want? Rapidly and easily create and deploy new plugins to optimize your complete app environment.

Learn More About PluginsIt's free, it's fast. Get the insights you need to improve your application's performance.

Michael Hartl

Contents

My former company (CD Baby) was one of the first to loudly switch to Ruby on Rails, and then even more loudly switch back to PHP (Google me to read about the drama). This book by Michael Hartl came so highly recommended that I had to try it, and the Ruby on Rails Tutorial is what I used to switch back to Rails again.

Though I've worked my way through many Rails books, this is the one that finally made me "get" it. Everything is done very much "the Rails way"-a way that felt very unnatural to me before, but now after doing this book finally feels natural. This is also the only Rails book that does test-driven development the entire time, an approach highly recommended by the experts but which has never been so clearly demonstrated before. Finally, by including Git, GitHub, and Heroku in the demo examples, the author really gives you a feel for what it's like to do a real-world project. The tutorial's code examples are not in isolation.

The linear narrative is such a great format. Personally, I powered through the Rails Tutorial in three long days, doing all the examples and challenges at the end of each chapter. Do it from start to finish, without jumping around, and you'll get the ultimate benefit.

Enjoy!

The Ruby on Rails Tutorial owes a lot to my previous Rails book, RailsSpace, and hence to my coauthor Aurelius Prochazka. I'd like to thank Aure both for the work he did on that book and for his support of this one. I'd also like to thank Debra Williams Cauley, my editor on both RailsSpace and the Ruby on Rails Tutorial; as long as she keeps taking me to baseball games, I'll keep writing books for her.

I'd like to acknowledge a long list of Rubyists who have taught and inspired me over the years: David Heinemeier Hansson, Yehuda Katz, Carl Lerche, Jeremy Kemper, Xavier Noria, Ryan Bates, Geoffrey Grosenbach, Peter Cooper, Matt Aimonetti, Gregg Pollack, Wayne E. Seguin, Amy Hoy, Dave Chelimsky, Pat Maddox, Tom Preston-Werner, Chris Wanstrath, Chad Fowler, Josh Susser, Obie Fernandez, Ian McFarland, Steven Bristol, Pratik Naik, Sarah Mei, Sarah Allen, Wolfram Arnold, Alex Chaffee, Giles Bowkett, Evan Dorn, Long Nguyen, James Lindenbaum, Adam Wiggins, Tikhon Bernstam, Ron Evans, Wyatt Greene, Miles Forrest, the good people at Pivotal Labs, the Heroku gang, the thoughtbot guys, and the GitHub crew. Finally, many, many readers-far too many to list-have contributed a huge number of bug reports and suggestions during the writing of this book, and I gratefully acknowledge their help in making it as good as it can be.

Michael Hartl is the author of the Ruby on Rails Tutorial, the leading introduction to web development with Ruby on Rails. His prior experience includes writing and developing RailsSpace, an extremely obsolete Rails tutorial book, and developing Insoshi, a once-popular and now-obsolete social networking platform in Ruby on Rails. In 2011, Michael received a Ruby Hero Award for his contributions to the Ruby community. He is a graduate of Harvard College, has a Ph.D. in Physics from Caltech, and is an alumnus of the Y Combinator entrepreneur program.

Ruby on Rails Tutorial: Learn Web Development with Rails. Copyright © 2013 by Michael Hartl. All source code in the Ruby on Rails Tutorial is available jointly under the MIT License and the Beerware License.

The MIT License Copyright (c) 2013 Michael Hartl Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy of this software and associated documentation files (the "Software"), to deal in the Software without restriction, including without limitation the rights to use, copy, modify, merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell copies of the Software, and to permit persons to whom the Software is furnished to do so, subject to the following conditions: The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all copies or substantial portions of the Software. THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED "AS IS", WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM, OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE SOFTWARE.

/* * ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- * "THE BEER-WARE LICENSE" (Revision 42): * Michael Hartl wrote this code. As long as you retain this notice you * can do whatever you want with this stuff. If we meet some day, and you think * this stuff is worth it, you can buy me a beer in return. * ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- */

Welcome to the Ruby on Rails Tutorial. The goal of this book is to be the best answer to the question, "If I want to learn web development with Ruby on Rails, where should I start?" By the time you finish the Ruby on Rails Tutorial, you will have all the skills you need to develop and deploy your own custom web applications with Rails. You will also be ready to benefit from the many more advanced books, blogs, and screencasts that are part of the thriving Rails educational ecosystem. Finally, since the Ruby on Rails Tutorial uses Rails 4, the knowledge you gain here represents the state of the art in web development. (The most up-to-date version of the Ruby on Rails Tutorial can be found on the book's website at http://railstutorial.org/; if you are reading this book offline, be sure to check the online version of the Rails Tutorial book at http://railstutorial.org/book for the latest updates.)

( Note: The present volume is the Rails 4.0 version of the book, which means that it has been revised to be compatible with Rails 4.0, but it is not yet a new edition because the changes in Rails don't yet justify it. From the perspective of an introductory tutorial, the differences between Rails 4.0 and the previous version, Rails 3.2, are slight. Indeed, although there are a large number of miscellaneous small changes ( Box 1.1), for our purposes there is only one significant difference, a new security technique called strong parameters, covered in Section 7.3.2. Once the changes in Rails justify the effort, I plan to prepare a full new edition of the Rails Tutorial, including coverage of topics such as Turbolinks and Russian doll caching, as well as some new aspects of RSpec, such as feature specs.)

It's worth emphasizing that the goal of this book is not merely to teach Rails, but rather to teach web development with Rails, which means acquiring (or expanding) the skills needed to develop software for the World Wide Web. In addition to Ruby on Rails, this skillset includes HTML & CSS, databases, version control, testing, and deployment. To accomplish this goal, the Ruby on Rails Tutorial takes an integrated approach: you will learn Rails by example by building a substantial sample application from scratch. As Derek Sivers notes in the foreword, this book is structured as a linear narrative, designed to be read from start to finish. If you are used to skipping around in technical books, taking this linear approach might require some adjustment, but I suggest giving it a try. You can think of the Ruby on Rails Tutorial as a video game where you are the main character, and where you level up as a Rails developer in each chapter. (The exercises are the minibosses.)

In this first chapter, we'll get started with Ruby on Rails by installing all the necessary software and by setting up our development environment ( Section 1.2). We'll then create our first Rails application, called (appropriately enough) first_app. The Rails Tutorial emphasizes good software development practices, so immediately after creating our fresh new Rails project we'll put it under version control with Git ( Section 1.3). And, believe it or not, in this chapter we'll even put our first app on the wider web by deploying it to production ( Section 1.4).

In Chapter 2, we'll make a second project, whose purpose is to demonstrate the basic workings of a Rails application. To get up and running quickly, we'll build this demo app (called demo_app) using scaffolding ( Box 1.2) to generate code; since this code is both ugly and complex, Chapter 2 will focus on interacting with the demo app through its URIs (often called URLs) using a web browser.

The rest of the tutorial focuses on developing a single large sample application (called sample_app), writing all the code from scratch. We'll develop the sample app using test-driven development (TDD), getting started in Chapter 3 by creating static pages and then adding a little dynamic content. We'll take a quick detour in Chapter 4 to learn a little about the Ruby language underlying Rails. Then, in Chapter 5 through Chapter 9, we'll complete the foundation for the sample application by making a site layout, a user data model, and a full registration and authentication system. Finally, in Chapter 10 and Chapter 11 we'll add microblogging and social features to make a working example site.

The final sample application will bear more than a passing resemblance to a certain popular social microblogging site-a site which, coincidentally, was also originally written in Rails. Though of necessity our efforts will focus on this specific sample application, the emphasis throughout the Rails Tutorial will be on general principles, so that you will have a solid foundation no matter what kinds of web applications you want to build.

Since its debut in 2004, Ruby on Rails has rapidly become one of the most powerful and popular frameworks for building dynamic web applications. Everyone from scrappy startups to huge companies have used Rails: 37signals, GitHub, Shopify, Scribd, Twitter, Disney, Hulu, the Yellow Pages-the list of sites using Rails goes on and on. There are also many web development shops that specialize in Rails, such as ENTP, thoughtbot, Pivotal Labs, and Hashrocket, plus innumerable independent consultants, trainers, and contractors.

What makes Rails so great? First of all, Ruby on Rails is 100% open-source, available under the permissive MIT License, and as a result it also costs nothing to download or use. Rails also owes much of its success to its elegant and compact design; by exploiting the malleability of the underlying Ruby language, Rails effectively creates a domain-specific language for writing web applications. As a result, many common web programming tasks-such as generating HTML, making data models, and routing URLs-are easy with Rails, and the resulting application code is concise and readable.

Rails also adapts rapidly to new developments in web technology and framework design. For example, Rails was one of the first frameworks to fully digest and implement the REST architectural style for structuring web applications (which we'll be learning about throughout this tutorial). And when other frameworks develop successful new techniques, Rails creator David Heinemeier Hansson and the Rails core team don't hesitate to incorporate their ideas. Perhaps the most dramatic example is the merger of Rails and Merb, a rival Ruby web framework, so that Rails now benefits from Merb's modular design, stable API, and improved performance.

Finally, Rails benefits from an unusually enthusiastic and diverse community. The results include hundreds of open-source contributors, well-attended conferences, a huge number of gems (self-contained solutions to specific problems such as pagination and image upload), a rich variety of informative blogs, and a cornucopia of discussion forums and IRC channels. The large number of Rails programmers also makes it easier to handle the inevitable application errors: the "Google the error message" algorithm nearly always produces a relevant blog post or discussion-forum thread.

The Rails Tutorial contains integrated tutorials not only for Rails, but also for the underlying Ruby language, the RSpec testing framework, HTML, CSS, a small amount of JavaScript, and even a little SQL. This means that, no matter where you currently are in your knowledge of web development, by the time you finish this tutorial you will be ready for more advanced Rails resources, as well as for the more systematic treatments of the other subjects mentioned. It also means that there's a lot of material to cover; if you don't already have much experience programming computers, you might find it overwhelming. The comments below contain some suggestions for approaching the Rails Tutorial depending on your background.

All readers: One common question when learning Rails is whether to learn Ruby first. The answer depends on your personal learning style and how much programming experience you already have. If you prefer to learn everything systematically from the ground up, or if you have never programmed before, then learning Ruby first might work well for you, and in this case I recommend Beginning Ruby by Peter Cooper. On the other hand, many beginning Rails developers are excited about making web applications, and would rather not slog through a 500-page book on pure Ruby before ever writing a single web page. In this case, I recommend following the short interactive tutorial at Try Ruby, and then optionally do the free tutorial at Rails for Zombies to get a taste of what Rails can do.

Another common question is whether to use tests from the start. As noted in the introduction, the Rails Tutorial uses test-driven development (also called test-first development), which in my view is the best way to develop Rails applications, but it does introduce a substantial amount of overhead and complexity. If you find yourself getting bogged down by the tests, I suggest either skipping them on a first reading or (even better) using them as a tool to verify your code's correctness without worrying about how they work. This latter strategy involves creating the necessary test files (called specs) and filling them with the test code exactly as it appears in the book. You can then run the test suite (as described in Chapter 5) to watch it fail, then write the application code as described in the tutorial, and finally re-run the test suite to watch it pass.

Inexperienced programmers: The Rails Tutorial is not aimed principally at beginning programmers, and web applications, even relatively simple ones, are by their nature fairly complex. If you are completely new to web programming and find the Rails Tutorial too difficult, I suggest learning the basics of HTML and CSS and then giving the Rails Tutorial another go. (Unfortunately, I don't have a personal recommendation here, but Head First HTML looks promising, and one reader recommends CSS: The Missing Manual by David Sawyer McFarland.) You might also consider reading the first few chapters of Beginning Ruby by Peter Cooper, which starts with sample applications much smaller than a full-blown web app. That said, a surprising number of beginners have used this tutorial to learn web development, so I suggest giving it a try, and I especially recommend the Rails Tutorial screencast series to give you an "over-the-shoulder" look at Rails software development.

Experienced programmers new to web development: Your previous experience means you probably already understand ideas like classes, methods, data structures, etc., which is a big advantage. Be warned that if your background is in C/C++ or Java, you may find Ruby a bit of an odd duck, and it might take time to get used to it; just stick with it and eventually you'll be fine. (Ruby even lets you put semicolons at the ends of lines if you miss them too much.) The Rails Tutorial covers all the web-specific ideas you'll need, so don't worry if you don't currently know a POST from a PATCH.

Experienced web developers new to Rails: You have a great head start, especially if you have used a dynamic language such as PHP or (even better) Python. The basics of what we cover will likely be familiar, but test-driven development may be new to you, as may be the structured REST style favored by Rails. Ruby has its own idiosyncrasies, so those will likely be new, too.

Experienced Ruby programmers: The set of Ruby programmers who don't know Rails is a small one nowadays, but if you are a member of this elite group you can fly through this book and then move on to developing applications of your own.

Inexperienced Rails programmers: You've perhaps read some other tutorials and made a few small Rails apps yourself. Based on reader feedback, I'm confident that you can still get a lot out of this book. Among other things, the techniques here may be more up-to-date than the ones you picked up when you originally learned Rails.

Experienced Rails programmers: This book is unnecessary for you, but many experienced Rails developers have expressed surprise at how much they learned from this book, and you might enjoy seeing Rails from a different perspective.

After finishing the Ruby on Rails Tutorial, I recommend that experienced programmers read The Well-Grounded Rubyist by David A. Black, Eloquent Ruby by Russ Olsen, or The Ruby Way by Hal Fulton, which is also fairly advanced but takes a more topical approach.

At the end of this process, no matter where you started, you should be ready for the many more intermediate-to-advanced Rails resources out there. Here are some I particularly recommend:

Before moving on with the rest of the introduction, I'd like to take a moment to address the one issue that dogged the Rails framework the most in its early days: the supposed inability of Rails to "scale"-i.e., to handle large amounts of traffic. Part of this issue relied on a misconception; you scale a site, not a framework, and Rails, as awesome as it is, is only a framework. So the real question should have been, "Can a site built with Rails scale?" In any case, the question has now been definitively answered in the affirmative: some of the most heavily trafficked sites in the world use Rails. Actually doing the scaling is beyond the scope of just Rails, but rest assured that if your application ever needs to handle the load of Hulu or the Yellow Pages, Rails won't stop you from taking over the world.

The conventions in this book are mostly self-explanatory. In this section, I'll mention some that may not be.

Both the HTML and PDF editions of this book are full of links, both to internal sections (such as Section 1.2) and to external sites (such as the main Ruby on Rails download page).

Many examples in this book use command-line commands. For simplicity, all command line examples use a Unix-style command line prompt (a dollar sign), as follows:

Windows users should understand that their systems will use the analogous angle prompt >:

On Unix systems, some commands should be executed with sudo, which stands for "substitute user do". By default, a command executed with sudo is run as an administrative user, which has access to files and directories that normal users can't touch, such as in this example from Section 1.2.2:

Most Unix/Linux/OS X systems require sudo by default, unless you are using Ruby Version Manager as suggested in Section 1.2.2.3; in this case, you would type this instead:

Rails comes with lots of commands that can be run at the command line. For example, in Section 1.2.5 we'll run a local development web server as follows:

As with the command-line prompt, the Rails Tutorial uses the Unix convention for directory separators (i.e., a forward slash /). My Rails Tutorial sample application, for instance, lives in

/Users/mhartl/rails_projects/sample_app

On Windows, the analogous directory would be

The root directory for any given app is known as the Rails root, but this terminology is confusing and many people mistakenly believe that the "Rails root" is the root directory for Rails itself. For clarity, the Rails Tutorial will refer to the Rails root as the application root, and henceforth all directories will be relative to this directory. For example, the config directory of my sample application is

/Users/mhartl/rails_projects/sample_app/config

The application root directory here is everything before config, i.e.,

/Users/mhartl/rails_projects/sample_app

For brevity, when referring to the file

/Users/mhartl/rails_projects/sample_app/config/routes.rb

I'll omit the application root and simply write config/routes.rb.

The Rails Tutorial often shows output from various programs (shell commands, version control status, Ruby programs, etc.). Because of the innumerable small differences between different computer systems, the output you see may not always agree exactly with what is shown in the text, but this is not cause for concern.

Some commands may produce errors depending on your system; rather than attempt the Sisyphean task of documenting all such errors in this tutorial, I will delegate to the "Google the error message" algorithm, which among other things is good practice for real-life software development. If you run into any problems while following the tutorial, I suggest consulting the resources listed on the Rails Tutorial help page.

I think of Chapter 1 as the "weeding out phase" in law school-if you can get your dev environment set up, the rest is easy to get through.

-Bob Cavezza, Rails Tutorial reader

It's time now to get going with a Ruby on Rails development environment and our first application. There is quite a bit of overhead here, especially if you don't have extensive programming experience, so don't get discouraged if it takes a while to get started. It's not just you; every developer goes through it (often more than once), but rest assured that the effort will be richly rewarded.

Considering various idiosyncratic customizations, there are probably as many development environments as there are Rails programmers, but there are at least two broad types: text editor/command line environments, and integrated development environments (IDEs). Let's consider the latter first.

The most prominent Rails IDEs are RadRails and RubyMine. I've heard especially good things about RubyMine, and one reader (David Loeffler) has assembled notes on how to use RubyMine with this tutorial. If you're comfortable using an IDE, I suggest taking a look at the options mentioned to see what fits with the way you work.

Instead of using an IDE, I prefer to use a text editor to edit text, and a command line to issue commands ( Figure 1.1). Which combination you use depends on your tastes and your platform.

- Text editor: I recommend Sublime Text 2, an outstanding cross-platform text editor that is simultaneously easy to learn and industrial-strength. Sublime Text is heavily influenced by TextMate, and in fact is compatible with most TextMate customizations, such as snippets and color schemes. (TextMate, which is available only on OS X, is still a good choice if you use a Mac.) A second excellent choice is Vim, versions of which are available for all major platforms. Sublime Text can be obtained commercially, whereas Vim can be obtained at no cost; both are industrial-strength editors, but in my experience Sublime Text is much more accessible to beginners.

- Terminal: On OS X, I recommend either use iTerm or the native Terminal app. On Linux, the default terminal is fine. On Windows, many users prefer to develop Rails applications in a virtual machine running Linux, in which case your command-line options reduce to the previous case. If developing within Windows itself, I recommend using the command prompt that comes with Rails Installer (Section 1.2.2.1).

If you decide to use Sublime Text, you might want to follow the optional setup instructions for Rails Tutorial Sublime Text. (Such configuration settings can be fiddly and error-prone, so I mainly recommend them for more advanced users; Sublime Text is an excellent choice for editing Rails applications even without the advanced setup.)

Although there are many web browsers to choose from, the vast majority of Rails programmers use Firefox, Safari, or Chrome when developing. All three browsers include a built-in "Inspect element" feature available by right- (or control-)clicking on any part of the page.

In the process of getting your development environment up and running, you may find that you spend a lot of time getting everything just right. The learning process for editors and IDEs is particularly long; you can spend weeks on Sublime Text or Vim tutorials alone. If you're new to this game, I want to assure you that spending time learning tools is normal. Everyone goes through it. Sometimes it is frustrating, and it's easy to get impatient when you have an awesome web app in your head and you just want to learn Rails already, but have to spend a week learning some weird ancient Unix editor just to get started. But, as with an apprentice carpenter striving to master the chisel or the plane, there is no subsitute for mastering the tools of your trade, and in the end the reward is worth the effort.

Practically all the software in the world is either broken or very difficult to use. So users dread software. They've been trained that whenever they try to install something, or even fill out a form online, it's not going to work. I dread installing stuff, and I have a Ph.D. in computer science.

-Paul Graham, in Founders at Work by Jessica Livingston

Now it's time to install Ruby and Rails. I've done my best to cover as many bases as possible, but systems vary, and many things can go wrong during these steps. Be sure to Google the error message or consult the Rails Tutorial help page if you run into trouble. Also, there's a new resource called Install Rails from One Month Rails that might help you if you get stuck.

Unless otherwise noted, you should use the exact versions of all software used in the tutorial, including Rails itself, if you want the same results. Sometimes minor version differences will yield identical results, but you shouldn't count on this, especially with respect to Rails versions. The main exception is Ruby itself: 1.9.3 and 2.0.0 are virtually identical for the purposes of this tutorial, so feel free to use either one.

Installing Rails on Windows used to be a real pain, but thanks to the efforts of the good people at Engine Yard-especially Dr. Nic Williams and Wayne E. Seguin-installing Rails and related software on Windows is now easy. If you are using Windows, go to Rails Installer and download the Rails Installer executable and view the excellent installation video. Double-click the executable and follow the instructions to install Git (so you can skip Section 1.2.2.2), Ruby (skip Section 1.2.2.3), RubyGems (skip Section 1.2.2.4), and Rails itself (skip Section 1.2.2.5). Once the installation has finished, you can skip right to the creation of the first application in Section 1.2.3.

Bear in mind that the Rails Installer might use a slightly different version of Rails from the one installed in Section 1.2.2.5, which might cause incompatibilities. To fix this, I am currently working with Nic and Wayne to create a list of Rails Installers ordered by Rails version number.

Much of the Rails ecosystem depends in one way or another on a version control system called Git (covered in more detail in Section 1.3). Because its use is ubiquitous, you should install Git even at this early stage; I suggest following the installation instructions for your platform at the Installing Git section of Pro Git.

The next step is to install Ruby. (This can be painful and error-prone, and I actually dread having to install new versions of Ruby, but unfortunately it's the cost of doing business.)

It's possible that your system already has Ruby installed. Try running

to see the version number. Rails 4 requires Ruby 1.9 or later and on most systems works best with Ruby 2.0. (In particular, it won't work Ruby 1.8.7.) This tutorial assumes that most readers are using Ruby 1.9.3 or 2.0.0, but Ruby 1.9.2 should work as well. Note: I've had reports from Windows users that Ruby 2.0 is sketchy, so I recommend using Ruby 1.9.3 if you're on Windows.